print, etching, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

romanesque

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 206 mm, width 264 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

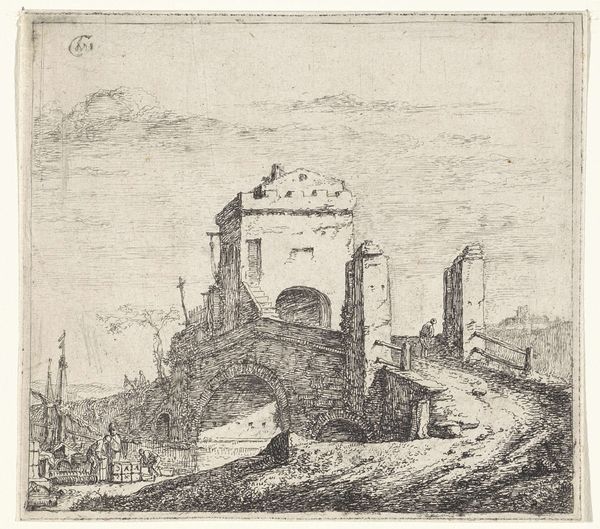

Curator: Welcome. We’re standing before Jan Gerritsz van Bronckhorst’s print, “Roman Ruins with Man and Donkey,” which dates from somewhere between 1613 and 1661. It’s an etching, showcasing a landscape punctuated by the remains of Roman architecture. Editor: It's quite evocative, a sort of melancholy scene. The ruins dominate the composition and they feel really monumental even in this small format, yet the palette makes the scene rather muted. There's a distinct sense of history, of empires past. Curator: Bronckhorst, like many artists of his time, was captivated by the grandeur of Rome and its enduring impact. This work reflects the fascination with antiquity during the Baroque period, which saw artists looking to the past for inspiration and authority. There’s a bit of an idealized vision presented here, too. Editor: Right, but beyond just inspiration, what does it signify that these artists consistently return to the image of ruins? It almost romanticizes imperial power, erasing perhaps the violence inherent in those structures, in Roman dominance itself. Who benefits from depicting the glories of Rome without acknowledging the marginalized voices, the enslaved peoples who built it? Curator: Well, the etching speaks to the tradition of the Grand Tour, a period where affluent Europeans traveled to Italy to study art and culture. Prints like these became souvenirs, emblems of classical knowledge and refinement. They perpetuated a specific understanding, a specific legacy, that underscored elite status and education. Editor: And even the choice of printmaking as a medium reinforces that. Reproducible, and therefore democratically distributed images of a hierarchical empire. Are we, in essence, re-inscribing the privilege in how we talk about the work? It reminds me of Edward Said's notion of Orientalism, of constructing narratives to assert power and otherness. Curator: It's true that art history is continually grappling with these questions, and these sorts of considerations are particularly important when considering how collections come into being and whose stories they tend to tell. Editor: It challenges us to see the layered narratives, the unseen labor, and power dynamics within seemingly picturesque landscapes, doesn’t it? It shows how representation and history-making can be potent political tools. Curator: Absolutely, it's about unraveling the social and political meanings embedded within art, and asking whose story is amplified, and at whose expense. I will carry these provocations as I continue researching how landscape is depicted, who inhabits that landscape and how. Editor: And I leave today also thinking more critically about these themes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.