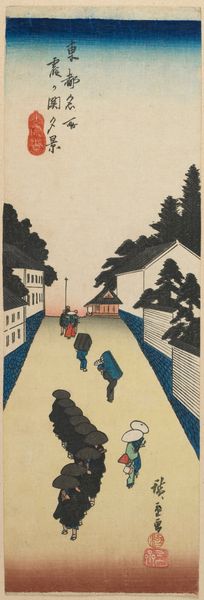

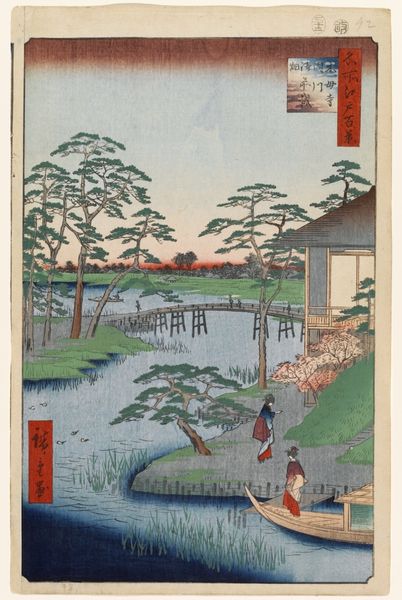

Viewing Cherry Blossoms from the Kiyomizu Hall at Tōeizan Temple in Ueno c. 1837 - 1838

0:00

0:00

print, ink, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

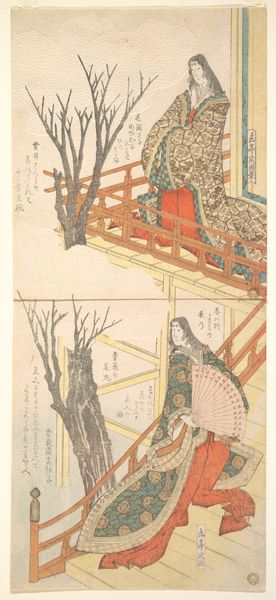

Dimensions: 14 13/16 × 5 in. (37.7 × 12.7 cm) (image, chūtanzaku)

Copyright: Public Domain

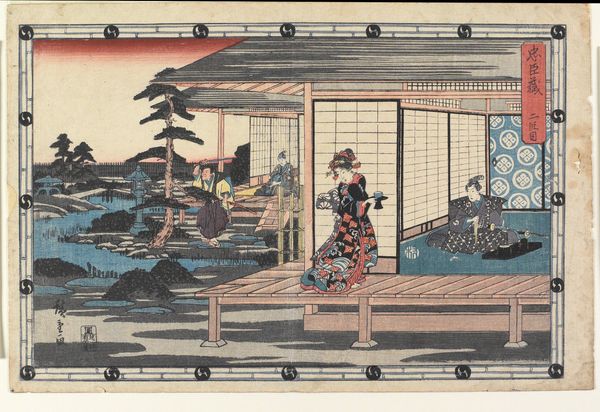

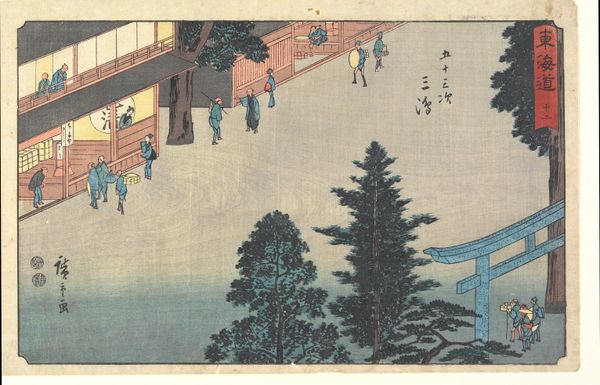

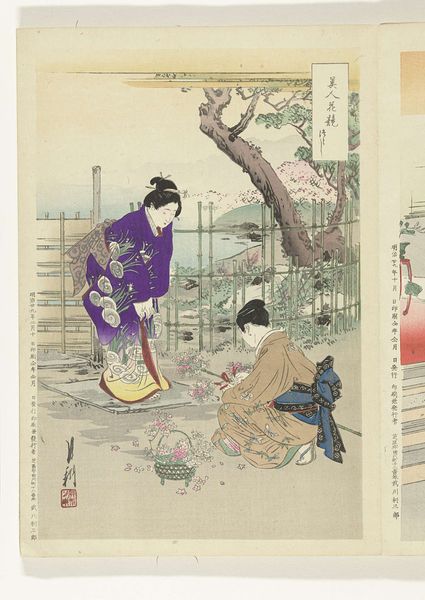

Curator: At first glance, this print evokes a sense of calm observation; the pastel hues and meticulously rendered details lend it an almost ethereal quality. Editor: We’re looking at Utagawa Hiroshige’s "Viewing Cherry Blossoms from the Kiyomizu Hall at Tōeizan Temple in Ueno," a woodblock print made sometime around 1837 or 1838. What draws you in, initially? Curator: The social stratification it subtly suggests. The woman on the veranda, elevated and adorned, compared to those on the ground level, navigating their paths. It hints at the distinct realities shaped by class within that society. Editor: Precisely. Hiroshige captures a moment in time but also comments on the social dynamics. How do you interpret the setting itself, this Kiyomizu Hall? Curator: As a site of both spiritual reverence and social gathering. The cherry blossoms themselves symbolize ephemerality, a reminder of life’s fleeting nature—a potent visual motif deeply embedded in Japanese art and culture. Are these elite classes represented properly to influence politics of imagery in a long term? Editor: The placement of the figures emphasizes this transience. People are framed *within* nature, subordinate to it. You know, the Kiyomizu-dera temple was relocated to Ueno Park, offering these incredible views, making it an instant tourist destination. The print therefore becomes part of that historical and institutional narrative too, documenting that shift and encouraging that same flow of bodies into public spaces. Curator: Which highlights the inherent tensions, doesn’t it? The desire for an unspoiled, natural vista and its entanglement within the frameworks of societal structures. It also reflects the tension in Ukiyo-e art, which sought to capture images of daily life that are equally artificial constructs. What did people have access to? Who could see it? Editor: A fascinating contradiction, indeed. As we observe these people engaging in what was intended as everyday leisure, Hiroshige leaves us with profound insights into a particular time. This allows us to question whose experiences and voices remain overlooked, silenced, or underrepresented in historical accounts. Curator: I appreciate the depth you bring to considering the print’s life beyond its creation, highlighting its public and ongoing roles in shaping our perceptions. Editor: And your ability to consider the piece through an intersectional lens allows for a richer, more nuanced interpretation. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.