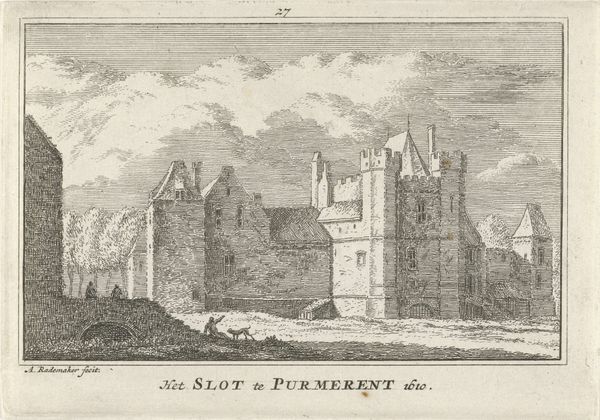

print, engraving, architecture

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 113 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Abraham Rademaker's "Gezicht op Slot Purmersteijn," an engraving likely created between 1725 and 1803. It depicts a now-vanished castle in the Netherlands. Editor: It’s a somber piece, isn’t it? The architectural details feel painstakingly rendered, but the light is very grey and austere; everything’s encased in this sort of decaying dignity. Curator: Rademaker's work often documented historical buildings, providing valuable records of structures that no longer exist. This print not only showcases his skill as an engraver but also offers a glimpse into the architectural landscape of the Dutch Golden Age, a period steeped in commercial expansion but often rife with internal power struggles and, sometimes, overt classism in its art. Editor: Engravings like these were crucial for disseminating images and information widely during that period. Think about the labor involved: the skilled craft of the engraver translating the architecture to metal. The way it circulates also interests me; these prints, destined for a merchant’s house, underscore material wealth through art acquisition. Curator: Precisely, and the subject matter isn't arbitrary. Castles, especially ones falling into ruin, serve as potent symbols. Whose narratives were literally and figuratively inscribed into these imposing buildings? How was social status reinforced by architecture, and who was structurally excluded? Editor: We could analyze the very materiality of the print: the quality of paper, the inks used, and where they were sourced, even the engraver’s tools. Each element holds clues about the print's journey into being, it echoes the network of resources needed for artistic production in that era. The figures in the foreground there, they look as though the landscape may also offer resources, too. Curator: Yes! And think about access, too. Prints like these offered a way for those without access to these buildings to view them and to contemplate these spaces from their own subjective positions, sometimes allowing entry points into critiques of power. Editor: Exactly. By appreciating the materials and means of creating this piece, along with its socio-historical context, it provides for a multi-layered experience for us. Curator: Ultimately, this small print invites us to consider the big issues surrounding art, architecture, and societal power. Editor: Yes, it’s a great point; to me, it brings an increased appreciation for art’s ability to reflect material culture while providing historical commentary.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.