drawing, plein-air, watercolor

#

drawing

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

house

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

Dimensions: sheet: 8 11/16 x 12 3/8 in. (22 x 31.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

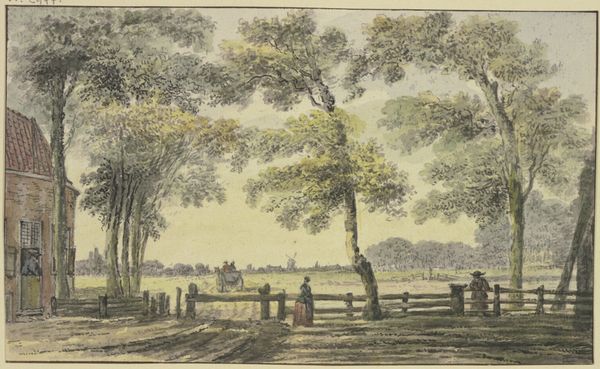

Curator: I’m struck by the serene stillness of this scene. It’s like a pause, a breath in the midst of something larger. Editor: This is "Italian Landscape with Trees (recto)", a watercolor and graphite drawing, completed circa 1815-1821 by Friedrich Salathé. It resides here at the Metropolitan Museum. These plein-air drawings by Salathé remind us of the early 19th century's fascination with both nature and Italy as destinations. Think about how travel and experiencing the landscape firsthand shaped artistic practices then. Curator: I agree; the travel context is important. And it’s more than just documenting a place, right? There is a romanticized vision of the Italian countryside being represented, particularly considering how landscapes function to symbolize liberty and autonomy. Do you agree that it seems deliberately positioned? The pastoral foreground almost serves as a stage, setting up some form of a theater. Editor: Certainly. He has chosen to depict this specific angle of the countryside – we are granted a certain idealized view here. There is an element of framing that is deliberately composed to encourage this sensation of freedom that the natural world enables for the figures within the composition. However, I wonder about how this freedom intersects with the socioeconomic realities. Were such bucolic experiences of travel accessible to most people in that time period? Curator: An incisive point. Whose freedom are we really looking at? The drawing might also unconsciously reveal hierarchies – even the very act of capturing this "untouched" nature becomes an act of appropriation. To unpack this further, it will also be important to observe how the very act of landscape painting at this period may or may not play into existing notions about the romantic ideals of nations, borders and identity during that era. Editor: Well, it certainly presents fertile ground for discourse on class and societal structures in a historical setting. By understanding who has access to landscape and nature at any point in history can definitely reveal quite a bit about power structures and nationalistic goals in general. It is the public role of such paintings like this one, in my view. Curator: Precisely, by considering the intersectionality in artwork analysis, one might get to broader insights and richer perspectives on cultural assumptions encoded within seemingly harmless representations of nature. Editor: A pertinent point of intersection that allows this simple yet intricate composition to take a different perspective and approach with its rich and accessible imagery and context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.