Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 173 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

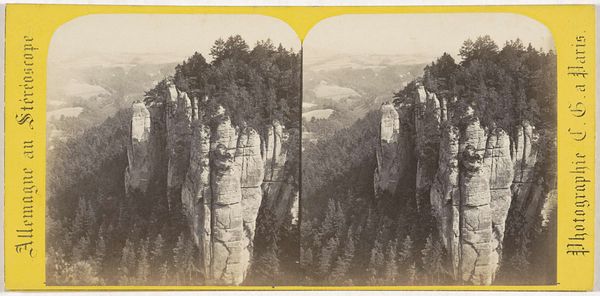

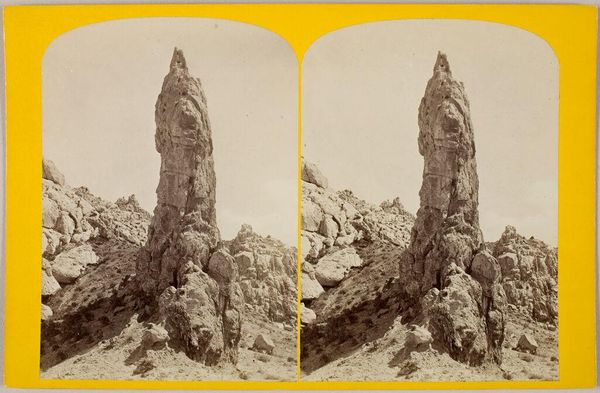

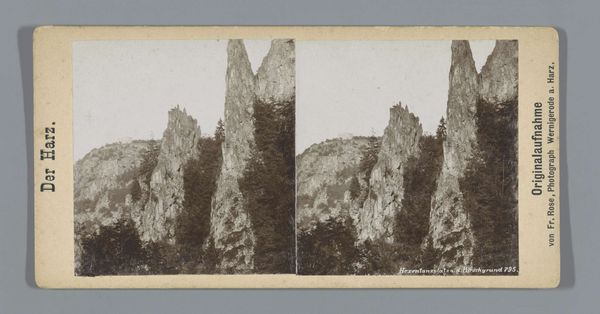

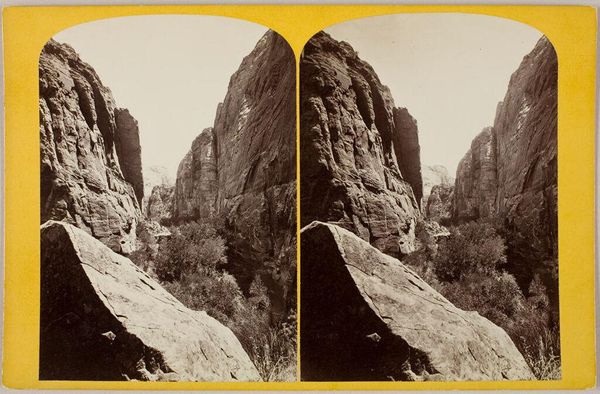

Curator: Charles Gaudin took this stereo photograph in 1868, showing Zandsteenrots Malý Pravčický Kužel in Bohemian Switzerland. Editor: There’s a stark beauty to this, almost severe. The sandstone formation, this obelisk really, has this uncanny presence, like some ancient monument guarding the land. It makes me think about geological timescales…it kind of blows my mind, honestly. Curator: Gaudin’s framing enhances the feeling. Look how he positions the rock pillar against the backdrop of the expansive forest, the layers of receding hills. Editor: Yes, and that choice is also implicated within early tourism practices in this region! The German name 'Bohemian Switzerland' speaks to the power of imposing Romantic ideologies upon landscape for a public increasingly encouraged to encounter "nature". This is further influenced, if you ask me, by histories of extraction in the region as sandstone quarries became very prominent during Gaudin's life. What we are seeing here, I think, is actually an encounter shaped by violent imperial gestures. Curator: Well, even with the industry around it, this place has undeniable spirituality about it. It's hard not to see this rock face and ponder time...the very slow pace it can operate on. To imagine its long silent existence... I am overcome with an urge for silent meditation just by seeing it. Editor: It is striking, no doubt. I wonder, what does it mean to isolate the solitary pinnacle to which the viewer has no possible access? I feel dislocated by that...there's some of that in Gaudin's choices here that mirror concerns with nationhood and citizenship that dominated Bohemian political movements later into the nineteenth century. I think that isolation is at once seductive and violent. Curator: Interesting. So we can agree it sparks thoughts... whether toward the geological, or the social and political implications of the place? It certainly gets you thinking. Editor: It does indeed, especially about our entangled relationships with the places we inhabit and document.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.