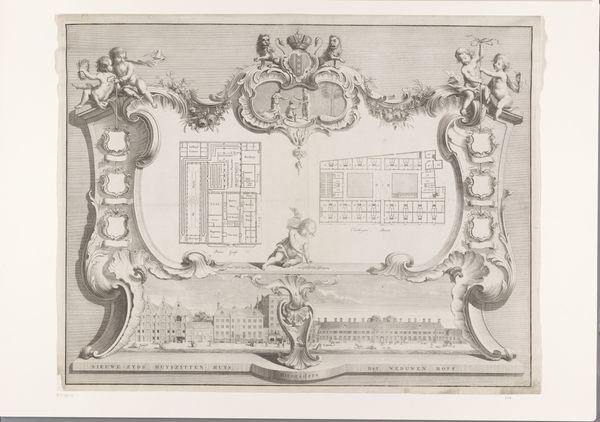

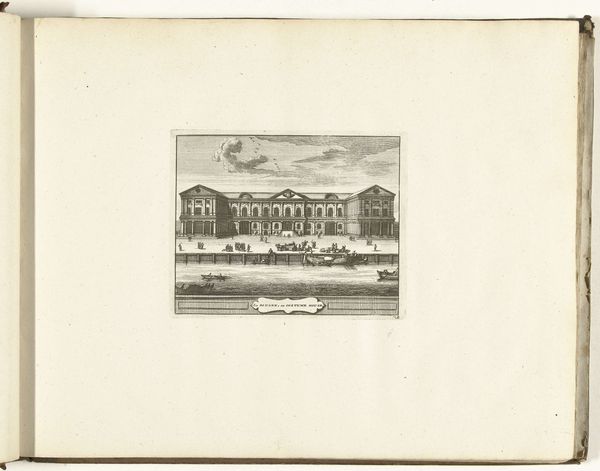

Twee stadsgezichten in Amsterdam met de Schreierstoren en met de Montelbaanstoren en het West-Indisch huis 1713 - 1766

0:00

0:00

hendrikdeleth

Rijksmuseum

engraving

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 208 mm, width 1020 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Hendrik de Leth's engraving, "Twee stadsgezichten in Amsterdam met de Schreierstoren en met de Montelbaanstoren en het West-Indisch huis," created sometime between 1713 and 1766. It’s a panoramic cityscape, and I’m struck by the detailed rendering of the ships and buildings. What do you notice when you look at this piece? Curator: Immediately, I'm drawn to the engraving process itself. Consider the labor involved in creating such detail with burins and plates. It speaks volumes about the value placed on visual representation and the consumption of these images by a burgeoning merchant class in Amsterdam. How does the medium of engraving influence our understanding of these cityscapes? Editor: That's fascinating. I hadn’t thought about the physical work behind it. Do you mean that the choice of engraving reveals something about how it was meant to be used, like, who would own it? Curator: Precisely. Engravings allowed for mass production, making these images accessible to a broader audience than a unique painting would be. They documented Amsterdam's power and prosperity – notice the towering ships which made that prosperity possible, connecting the city to global trade networks. But also consider where the copper came from for the plate. And who owned the workshops? It makes you consider how these things are interconnected. Editor: So, it's not just a picture of Amsterdam, but a record of its economic structure and social standing? And the engraving becomes part of that record, itself? Curator: Exactly. This piece then embodies and reproduces the material conditions of its creation, offering valuable insights into Dutch Golden Age society, as the source of prosperity and how that influences not only *what* is depicted but *how*. Editor: I hadn’t really thought about the means of production being a part of what’s *being* depicted, so to speak. Curator: Yes! Thinking through production reveals power structures often obscured by beauty. We must ask, whose labor made this image possible, and for whom was it intended? Editor: That definitely provides a richer understanding of the work. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.