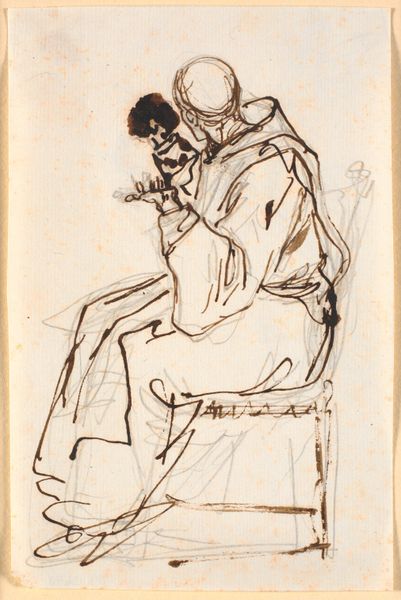

Portrait of the Sculptor Auguste Rodin in his Studio c. 1889

0:00

0:00

drawing, gouache, ink, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

self-portrait

#

impressionism

#

gouache

#

figuration

#

ink

#

france

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

portrait art

#

realism

Dimensions: 582 × 395 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Jean-François Raffaëlli’s “Portrait of the Sculptor Auguste Rodin in his Studio,” dating to around 1889, currently housed at the Art Institute of Chicago. I find it fascinating how Raffaëlli captured the act of creation, with Rodin completely absorbed in his work. How do you approach understanding a piece like this, focused on another artist? Curator: I'm drawn to how the work portrays Rodin's studio as a space of labor, where art is produced. Consider the visible materials: charcoal, ink, gouache, all used to depict Rodin’s own sculptural practice. The drawing itself becomes a document of the artistic process. Raffaëlli is not just creating a likeness, he's presenting Rodin at work, within the physical context of his production. Think about the stool and its tray: are they just props, or do they point to a whole network of production? Editor: That's a good point, I hadn’t considered how much the studio contributes. So it's not just about Rodin’s genius, but also about the tools and environment that enable that genius? Curator: Exactly. What kind of impressionist strategies of making is Raffaëlli using to show a peer at work? Notice the loose, visible mark-making. Raffaëlli is representing the textures of both Rodin's sculpting materials and his own drawing tools. Consider what it says about artistic labor at the time – this wasn’t just inspiration, but craft, a kind of ‘working man’ vision. Editor: So the materials used in the portrait, mirror the materials and practice of Rodin? Almost a form of homage by shared physicality? Curator: Yes, consider it as an act of artistic solidarity shown through materials and labor. In its time period, the emphasis was changing from the old Academy vision of sublime subjects and mastery to the everyday world, but there was also the rising trend of ‘art for art’s sake.’ What are your thoughts on that position, and this work? Editor: It’s interesting to think of Raffaëlli commenting on that by connecting the grand art with the labour-intensive practice of it. It brings a new perspective on portraits of artists I hadn’t considered before. Curator: Precisely, we start looking beyond representation to engage with the tangible conditions of artistic production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.