tempera, fresco

#

portrait

#

tempera

#

painted

#

figuration

#

fresco

#

oil painting

#

jesus-christ

#

christianity

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

christ

Copyright: Public domain

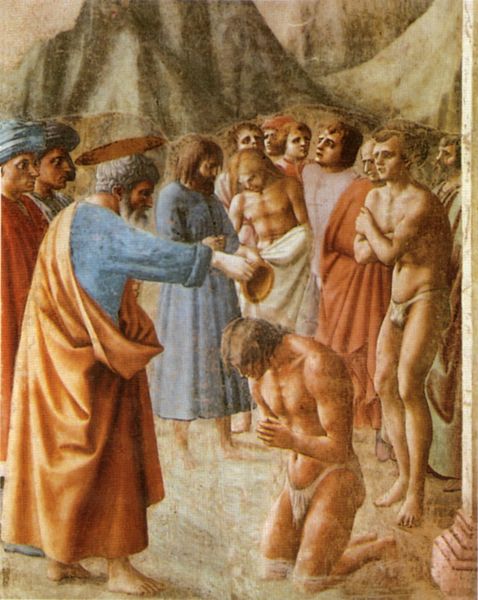

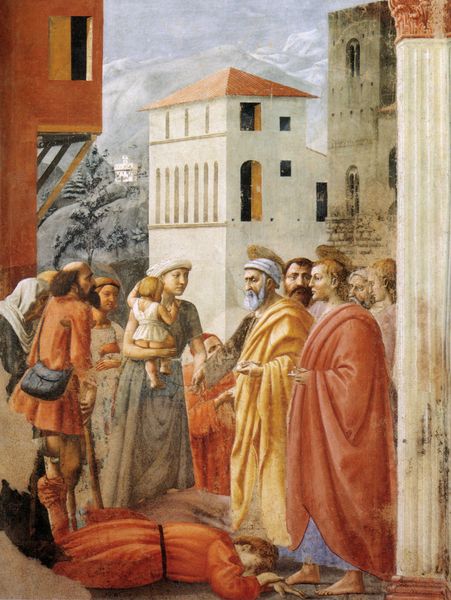

Editor: Here we have Masaccio's "The Tribute Money," a fresco from around 1425, located in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence. It strikes me how realistically the figures are rendered; there’s such a human quality to them. What do you see in this piece? Curator: The beauty of this fresco lies, for me, in understanding its creation within the socio-economic context of Florence at the time. Consider the availability of materials – the pigments sourced from local workshops, the preparation of the wall surface for the fresco technique, requiring skilled labor. How does this production, these economic realities, affect our reading of the narrative itself? Editor: That’s a really interesting point. I'd never thought of it that way. I was focusing on the biblical story and the expressions of the figures. Curator: Exactly. But aren’t those expressions and gestures rendered through material means? Pigments ground and applied by hand, shaped by the cultural and economic landscape of Renaissance Florence? It is through understanding production that we may understand the true symbolic intent of this tribute. It becomes less about simple religious dogma and more about socio-economic power. Editor: So you are saying the physical act of making the artwork with specific resources reveals something deeper about society at the time? Curator: Precisely. The materials themselves, the human labor involved – all contribute to a powerful commentary on the society that produced it, and the stories it chose to tell. Editor: That’s given me a completely new way of looking at it! I was so focused on the narrative, and now I see how the materials and production tell their own story. Curator: Indeed. Art isn’t just what we see on the surface; it's also the physical manifestation of culture, shaped by hands and resources, forever connecting us to the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.