photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

historical fashion

#

realism

Dimensions: height 221 mm, width 164 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

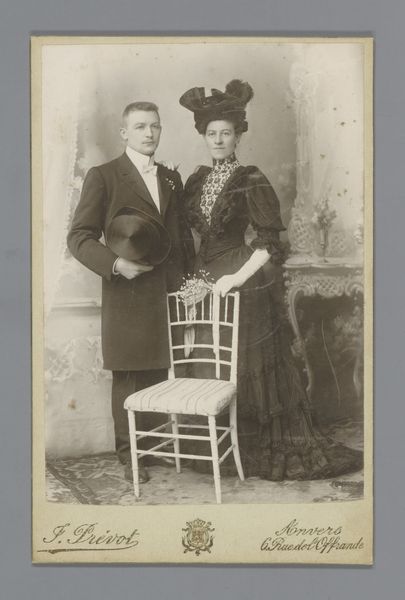

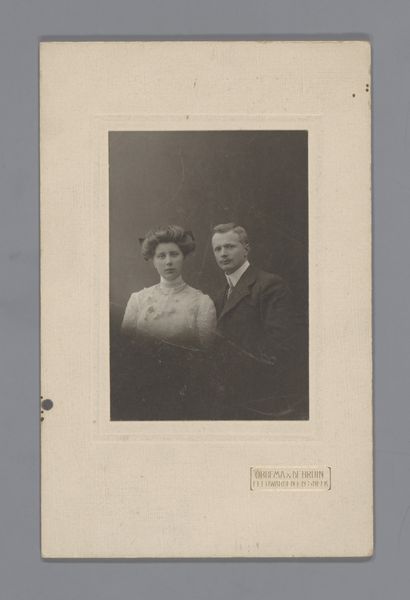

Editor: Here we have a portrait, "Portret van een man en een vrouw op een bank," a photograph from sometime between 1915 and 1926. It feels very staged, almost stiff. What strikes you when you look at this photo? Curator: Well, what interests me immediately is the production itself. This isn't just a simple snapshot. The careful posing, the studio backdrop, even the quality of the paper used, speak to the commercialisation of portraiture during this period. Editor: Commercialisation? How so? Curator: Think about it. Photography transitioned from a rare, expensive luxury to a more accessible service. Studios like Steenmeijer’s emerged, providing relatively affordable ways for everyday people to document themselves, often emulating the conventions of painted portraiture, which you see here in the formal attire. The material reality – the photographic paper, the developing chemicals – all were becoming standardized for wider consumption. What can you infer about the economics of the portrait process, given what you can observe? Editor: So, the photograph becomes a commodity. I suppose before only the wealthy could afford a painted portrait, but this offers a new way to display status. Curator: Exactly. The very act of sitting for this photo – the labour of the photographer, the sitter’s financial investment in their appearance – signifies a participation in a burgeoning consumer culture. How do their clothes factor into the setting? Editor: Good point. The fashions they're wearing help determine its cultural setting, so one could imagine how material and textile production processes influenced these popular trends. I see this photo as less about who they are, but the ways photography itself democratized image creation at that point in time. Thanks for helping me think about photography and labour! Curator: Of course! It’s precisely through understanding these processes, this material history, that we can truly start to decipher the image's message beyond the surface representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.