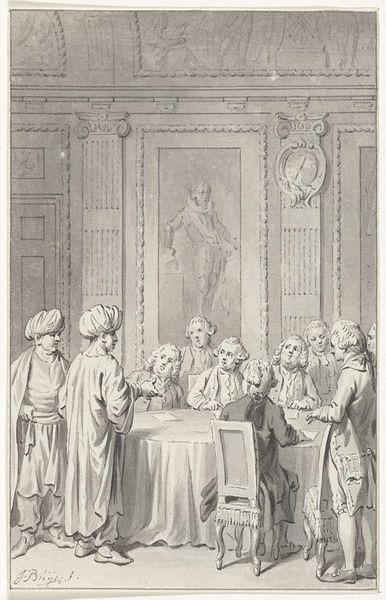

Willem V neemt voor het eerst zitting in de Raad van State, 1763 1795 - 1797

0:00

0:00

reiniervinkeles

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 155 mm, width 91 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Oh, this piece is interesting, isn't it? Made sometime between 1795 and 1797, it’s titled "Willem V neemt voor het eerst zitting in de Raad van State, 1763," and it's attributed to Reinier Vinkeles. It depicts Willem V taking his seat in the Council of State for the first time. The work is done in etching and engraving. What catches your eye first? Editor: Hmm, the sheer gravity of the scene. It feels...claustrophobic, almost. A somber moment captured in those fine, precise lines. Is it me, or does the lighting amplify the weight of responsibility on young Willem’s shoulders? Curator: Absolutely! It’s designed to portray the solemnity of the occasion. Vinkeles has rendered the scene to highlight the decorum of statecraft, while two portraits on the wall further legitimize the represented space. Willem is positioned to become part of an important dynastic continuum. It underscores the power dynamics, doesn’t it? Editor: Precisely. And, of course, being a print, it was meant for wide dissemination. What impact do you think imagery like this would have had on public opinion during a period of shifting political landscapes? Surely this isn't *just* a commemorative scene, right? Curator: It definitely served multiple purposes. Prints like these were tools to legitimize authority. Willem's early reign wasn’t without turmoil, so the print helps underscore the historical precedents validating his rule. And that "old engraving style," as the kids call it, really harkens back to older visual strategies used for portraying authority and legitimation. Editor: True, every detail seems carefully considered, every face a study in composed deliberation. I can’t help but wonder, though: how much of this is real, and how much is a performance of power for the sake of the viewing public? After all, who is not in this image, and how does that absence re-configure how we read it? Curator: Well, these sorts of images tend to erase as much as they reveal. That is where historical analysis can intervene and fill in the gaps. At the end of the day, it all returns to Vinkeles' strategic decisions, framing history not just as it happened but as someone wished it to be remembered. Editor: Which is something worth reflecting on every time we consider an artwork from the past, I think. It is a reminder that how we frame something ultimately shapes how it is understood, or not. Curator: Absolutely. Each element serves a purpose beyond mere depiction. They all feed into a narrative about leadership, legitimacy, and legacy, all very strategically composed in service to its moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.