drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

cityscape

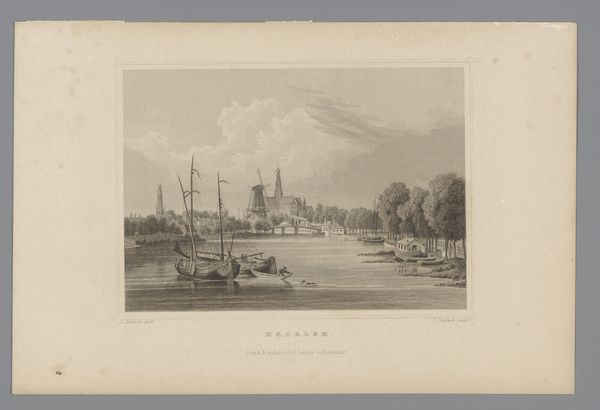

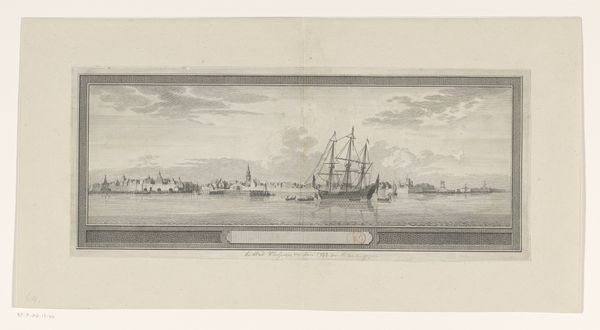

Dimensions: height 177 mm, width 250 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Carel Frederik Bendorp's 1786 etching, "Gezicht op Werkendam," currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It feels incredibly still, almost serene. The lines are so fine, rendering this Dutch town and the broad sky with impressive clarity, even from this distance. What was etching's place within printmaking practices at the time? Curator: Etching, as opposed to engraving, allowed for a freedom of line closer to drawing, lending itself to this type of landscape rendering that was becoming quite popular, showcasing both a realistic depiction and the artistry of the hand. It enabled printmakers like Bendorp to reach a broader audience with affordable views of Dutch towns. We must consider that the lines created here are results of labor processes as part of landscape art consumption that had the impact of fostering Dutch national pride. Editor: That broader access is crucial to acknowledge. Looking at the detail, you can almost feel the weight of labor—people actively engaged in moving goods, transporting, sustaining their town. The inclusion of a church in the landscape suggests the integral role of religion, so perhaps this artwork speaks to the complex, multifaceted lives lived at Werkendam. What social classes had enough capital to obtain it, and how does its availability engage and challenge conversations surrounding land ownership? Curator: That’s the crucial dialogue we want to encourage. Beyond its accessibility as a relatively inexpensive print, Bendorp’s technique further democratized the image, relying on acid to “bite” the image into the plate, rather than exclusively on the engraver's strength. While Bendorp presents the scene, it’s the chemical process that truly allows its duplication. What about the sailboats do you observe, and do their materiality factor into discussions of economy and mobility during this period? Editor: I do think their position relative to the town invites questions about Werkendam's position in trade networks, connecting the local community to global flows of capital, or, inversely, representing how this local space might have been influenced and even exploited within unequal international power dynamics. Curator: Absolutely. Examining how such prints were distributed and received informs us on social hierarchies but also on art as an exchangeable good that facilitated this dissemination of knowledge about landscapes. It challenges how landscapes can contribute to social awareness and activism. Editor: Looking again at the calm stillness Bendorp evokes, I think it gives one pause—a reminder perhaps to be critical of the ease of such images and think more deeply about what the labor, the landscape, the etching processes represent. Curator: I couldn’t agree more. Appreciating it technically certainly enriches our understanding, but recognizing it as part of the circulation of goods and ideas, gives it more lasting significance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.