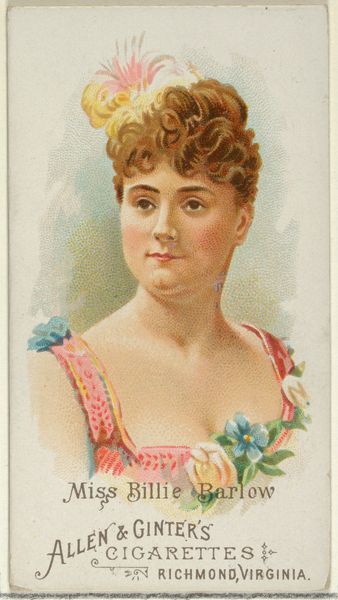

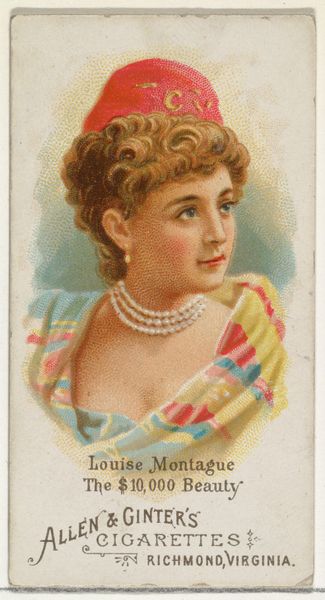

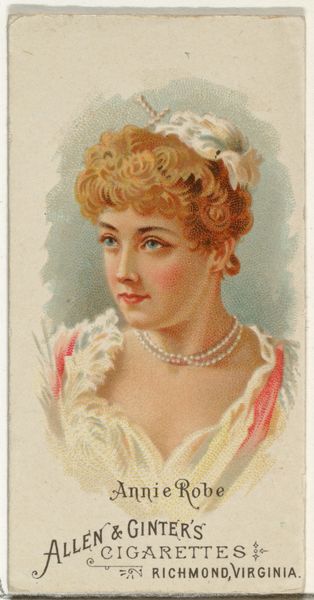

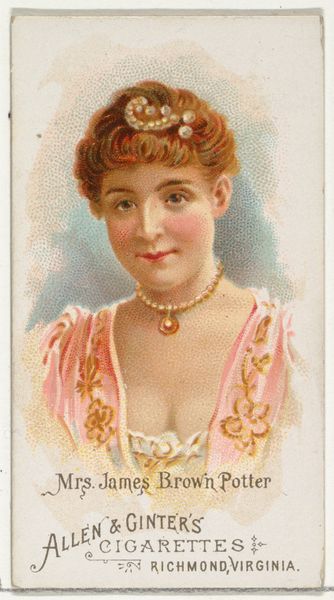

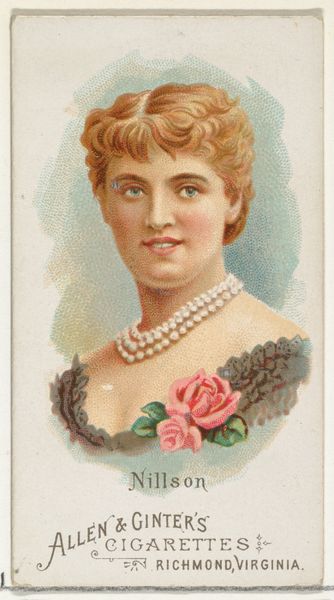

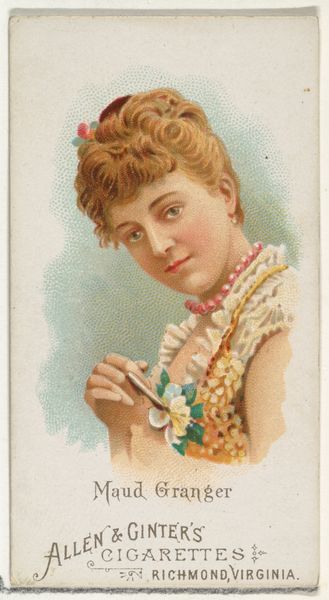

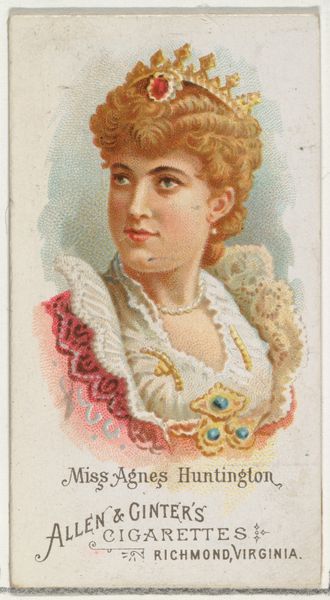

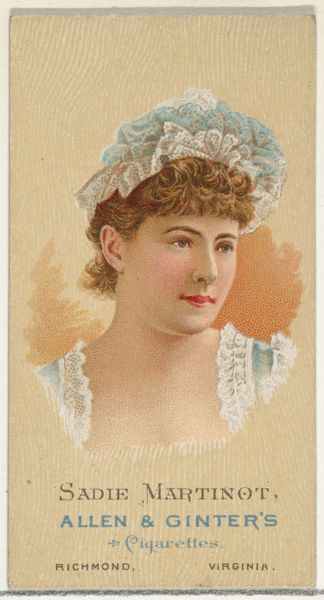

Miss Ethel Selwyn, from World's Beauties, Series 1 (N26) for Allen & Ginter Cigarettes 1888

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

impressionism

#

caricature

#

paper

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 3/4 x 1 1/2 in. (7 x 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "Miss Ethel Selwyn," a print from 1888, part of the "World's Beauties" series by Allen & Ginter Cigarettes. It's a charming portrait, but it's also advertising. How do we unpack that relationship between art, commodity, and portraiture here? Curator: Excellent starting point. Let’s focus on the cigarette card itself as an object. It’s made of paper, a relatively inexpensive material, printed en masse. This makes it immediately accessible to a wide audience, tying into the rise of consumer culture. Think about the labour involved – from the paper mill workers to the illustrators and the factory employees packing these into cigarette boxes. This 'art' is deeply embedded in a system of production and distribution. Editor: So, the image of "beauty" is being mass-produced, consumed alongside cigarettes, and arguably devalued in the process? Curator: Precisely. What does it mean to portray beauty within such a commercial context? It's not just about aesthetics anymore, it's about constructing a desire, a brand identity. Ethel Selwyn becomes a symbol linked to Allen & Ginter’s cigarettes – a marker of status and taste purchased alongside the product itself. The card’s survival as a collectible today further complicates the history of labor and material it stands upon. Editor: That really shifts my perspective. I initially saw it as a pretty portrait, but it's fascinating to think about it as a material object connected to labor and consumption. Curator: It shows how looking at materials and means of production reveal a network of relationships tied to commodity culture that complicate the traditional category of 'high art'. A print of this nature broadens the consumption and accessibility to the field of artistry beyond wealthy classes. Editor: Absolutely, I am eager to think about the art production's role in culture! Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.