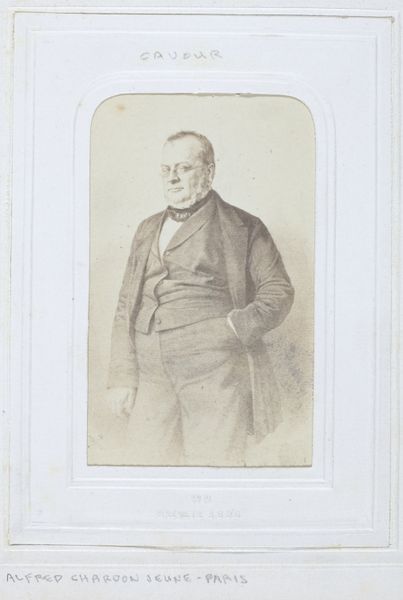

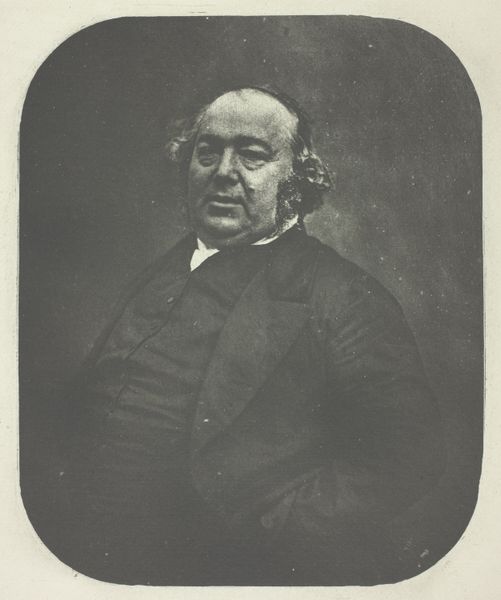

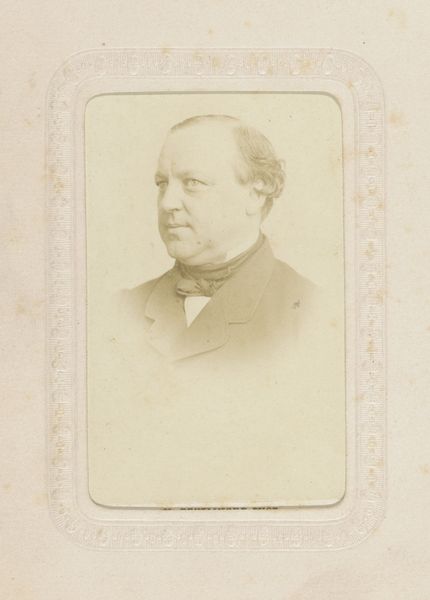

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

men

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

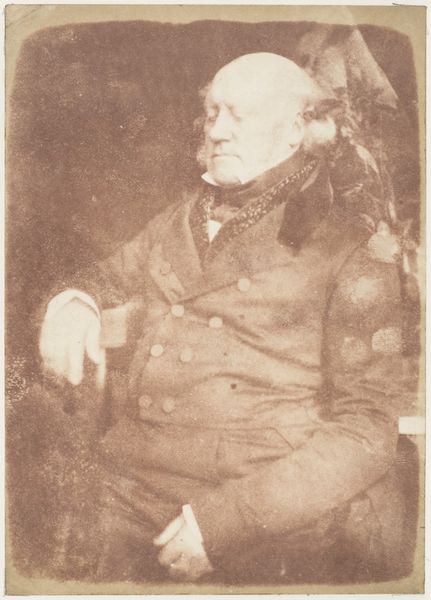

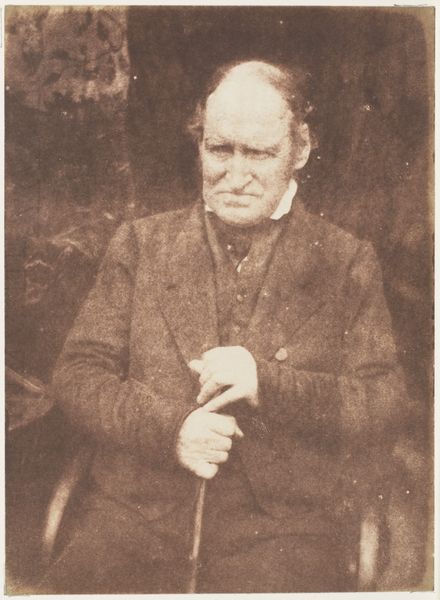

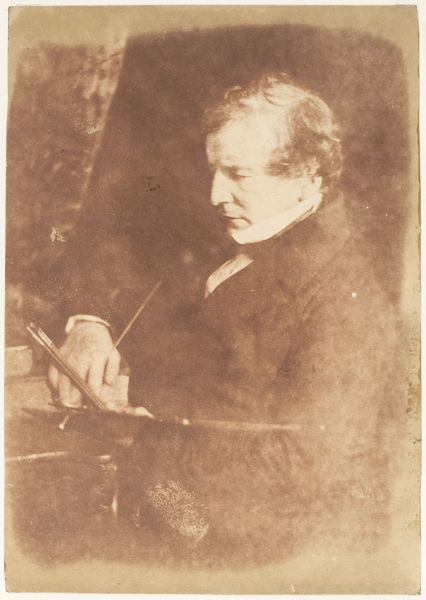

Editor: Here we have "Dr. Sampson of York," a daguerreotype portrait created between 1843 and 1847 by Hill and Adamson. The tones are sepia, and it possesses a solemn stillness. What strikes me is the formality—what do you make of it? Curator: Formality, yes, but consider its revolutionary context. Early photography emerged during a period of immense social upheaval, particularly concerning class structures and representation. Portraiture, once the exclusive domain of the wealthy, was suddenly accessible to a wider audience. Do you see how the subject's clothing and pose attempt to convey a specific status? Editor: I do. His serious gaze and attire are purposeful, intending to denote sophistication. However, there is something inherently democratic about making portraiture more widely accessible through this new medium. Curator: Exactly. While consciously emulating the established conventions of painted portraiture, the daguerreotype inherently challenged them. Photography gave new agency to those previously excluded from such visual narratives. We can also read the constraints. What does this fixed pose indicate to you? How does it compare to our contemporary image-making culture? Editor: Right, I didn't think about the technical restraints of early photography. The stillness makes it almost painterly, even though it's radically different from painting. And the photograph arguably democratizes image creation and circulation... Curator: It hints at power dynamics but also anticipates challenges to them. The very act of capturing and disseminating this image represents an early shift towards a more visually inclusive society, though the reality was far more complex, obviously. Editor: This makes me rethink the way I view early photography – as something both conventional and revolutionary. Thanks! Curator: It reveals the tension between inherited privilege and the democratization of representation, and that tension remains pertinent to contemporary discussions around photography today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.