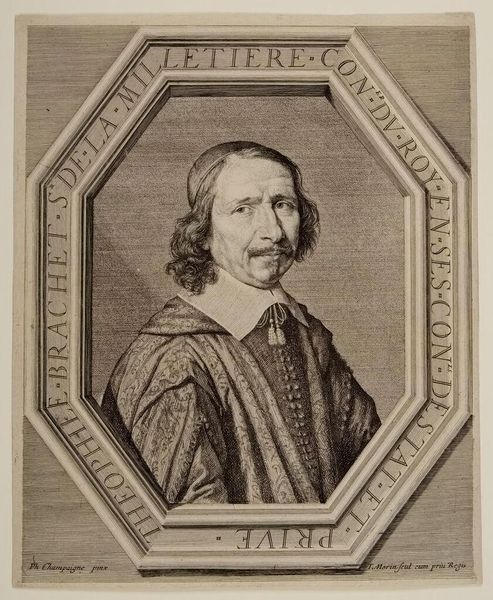

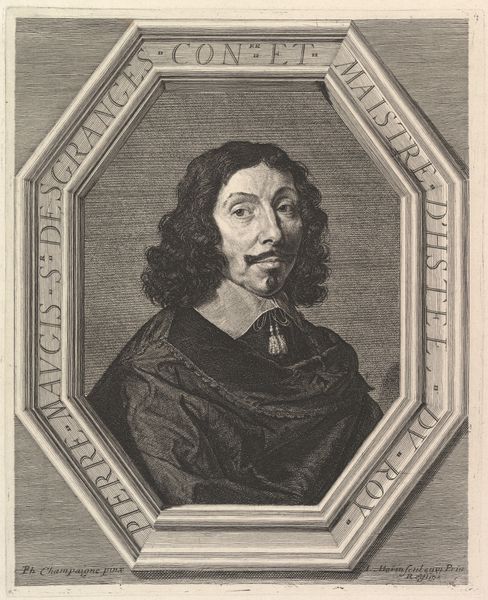

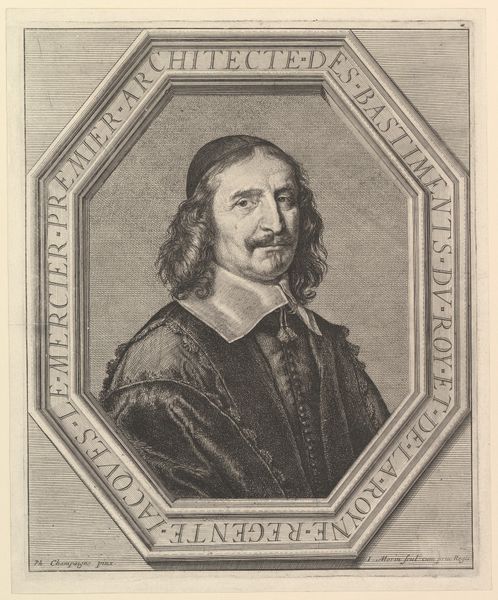

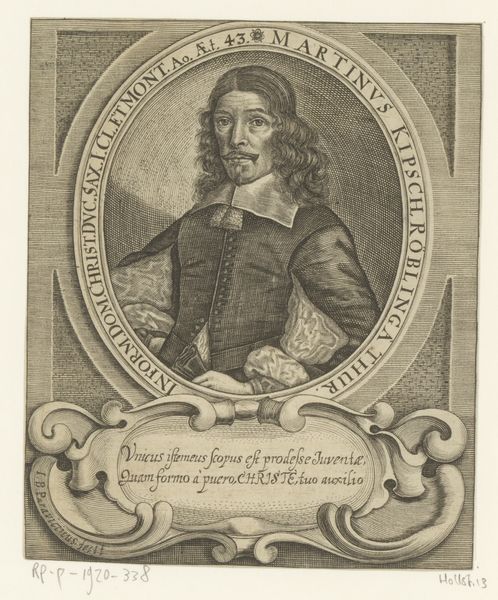

Theophile Brachet de la Milletiere, conseiller du roi 1605 - 1650

0:00

0:00

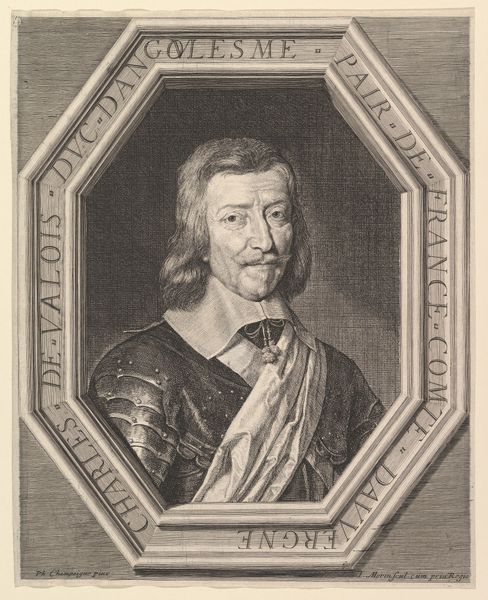

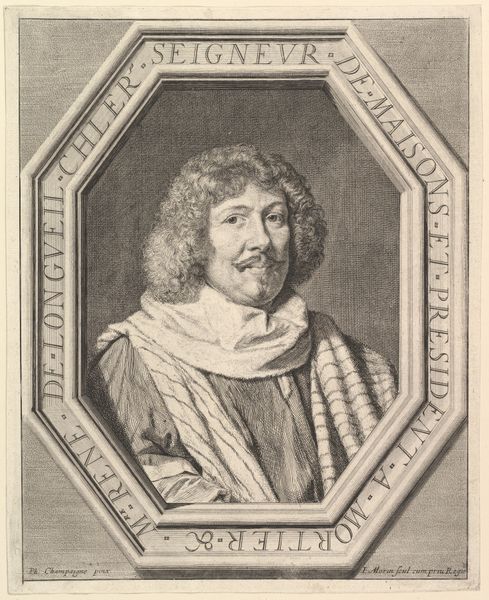

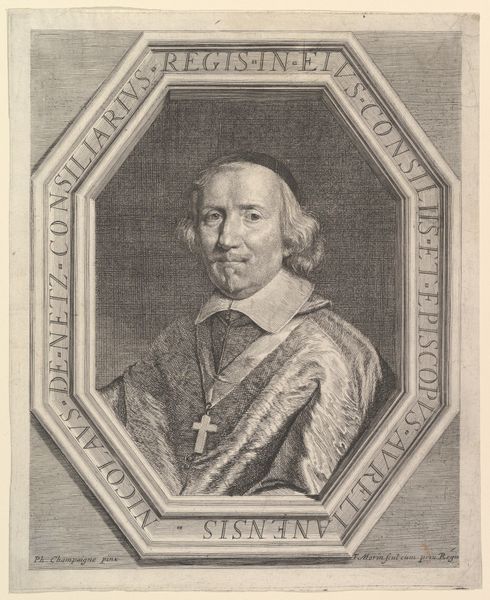

drawing, print, metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

metal

#

old engraving style

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 12 5/8 x 10 3/8 in. (32 x 26.4 cm) image: 11 13/16 x 9 7/16 in. (30 x 24 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is an engraving of "Theophile Brachet de la Milletiere, conseiller du roi," dating between 1605 and 1650, made by Jean Morin. It has a sort of solemn feel. What social and political dynamics do you think it reflects? Curator: Absolutely. Portraits during this era weren’t just about capturing a likeness. Consider who Theophile Brachet de la Milletiere was—a king's counselor. His position implies power, influence. Think about how the image reinforces the strict social hierarchies of the time, particularly the role of men in positions of power. How does the very medium, engraving, play into that message of authority? Editor: Because it could be reproduced, right? Spreading his image and therefore his authority? Curator: Precisely! It allowed for a wider dissemination of his image, thereby reinforcing his position in society. It almost performs a kind of social coding, doesn’t it? Also, what does the formal framing device suggest? Editor: That he should be admired from a distance, like royalty, separated from the everyday? Curator: Indeed. The frame isolates and elevates him. Consider also the gaze of the subject—direct, unwavering. This assertion of self is further reinforced through the material wealth denoted in his attire, implying the privilege inherent in his social standing. It tells a story of class, power, and the structures upholding them. Editor: So it's not just a picture; it’s a carefully constructed statement about power. I hadn't thought about the role of reproducibility in amplifying that. Curator: Exactly. Reflecting on these issues allows us to unravel not just the image, but also the complex layers of 17th-century social dynamics. We can question how portraits participated in reinforcing power imbalances and, perhaps more interestingly, who was excluded from such representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.