#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public domain

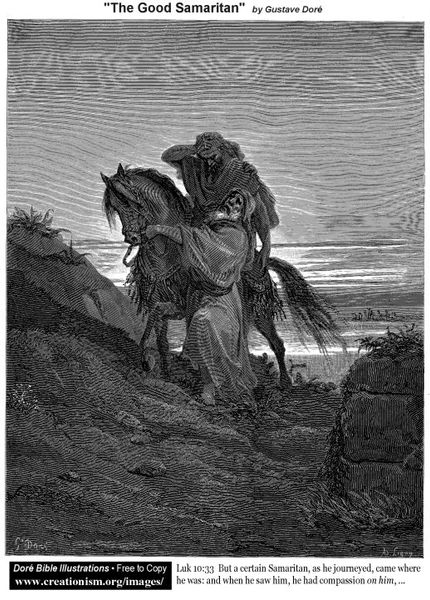

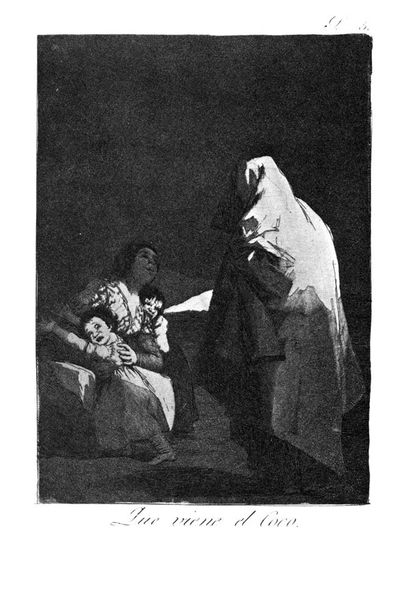

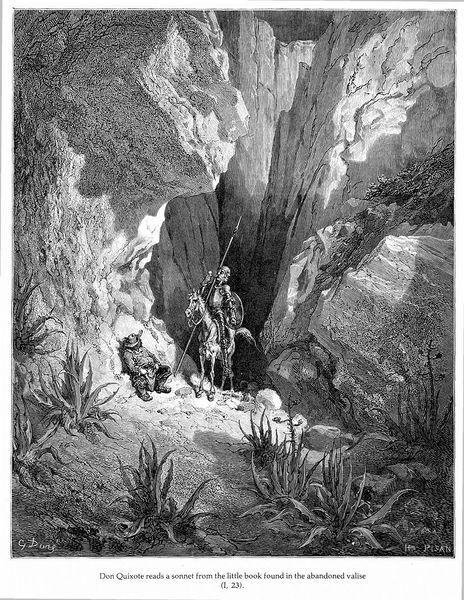

Curator: Welcome. We’re standing before James Tissot’s 1900 print, "Balaam and the Ass, as in Numbers," a striking depiction of a scene from the Hebrew Bible. Editor: It feels theatrical, almost staged. The stark contrasts create a dramatic atmosphere, like a scene pulled from a morality play. The figures are so rigidly posed. It is as if Tissot is highlighting a very specific reading of scripture. Curator: Indeed. Tissot was known for his detailed narrative scenes, particularly those drawn from biblical texts. This work comes from a period where there was increased academic interest in biblical studies. His prints often reflect this scholarly approach and were exhibited widely. Think about how he uses the medium of print itself. It allows the image to circulate widely, enabling different social classes to engage with scripture visually. Editor: What I find compelling here is the clear power dynamic being visualized. Balaam, the supposed prophet, is quite literally on his ass. His body language screams submission, whereas the angel looks indifferent to him, despite wielding what appears to be a very long sword. It’s as though Tissot invites us to confront the imbalances in power. How do you perceive the ass in this narrative? Surely there is more to it than sheer transportation. Curator: Ah, yes. That would bring us back to a more sociological reading. The ass sees what Balaam cannot, and thus becomes an unlikely savior for Balaam who cannot see the injustices of his time. His role highlights how marginalized figures often have unique perspectives obscured to the powerful. One might question how the artist viewed his own place in the social hierarchy through this portrayal. Editor: And this brings us back to my earlier comment. The stage for that story is created by sharp contrasts, not least because the print offers the luxury of simplification. This allows a reading about how moral narratives are built and how they should invite discussions and actions related to injustices we might experience around us in society, or not, as this print suggests. It makes us reflect on who we perceive as seeing and acting when so many do not. Curator: That is an interesting point and one of the wonderful possibilities available when approaching artworks through contemporary interpretation. It certainly gives a lot to think about. Editor: It does. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.