print, photography, albumen-print, architecture

# print

#

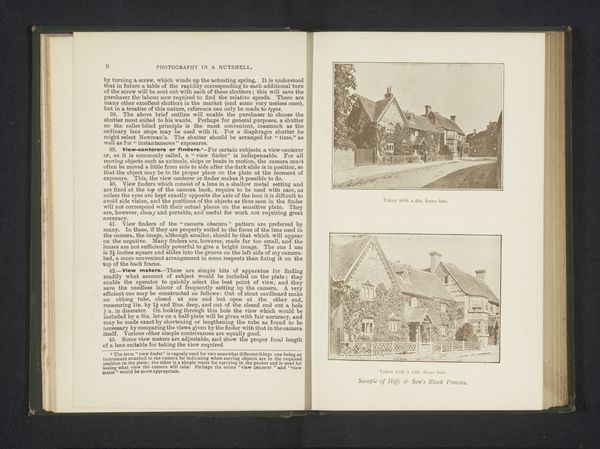

photography

#

orientalism

#

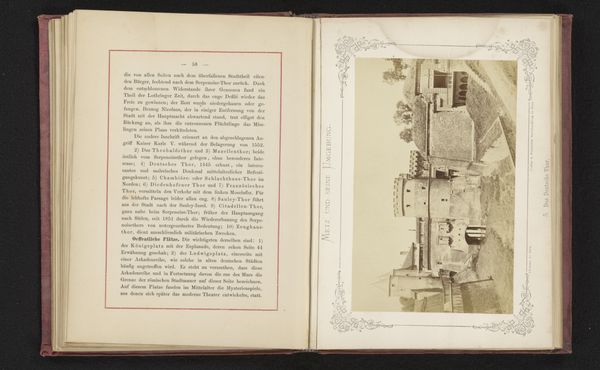

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

#

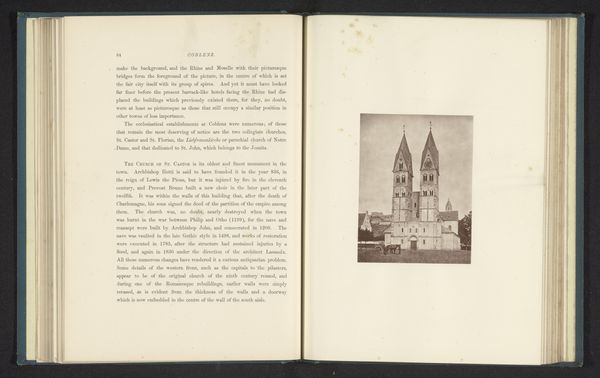

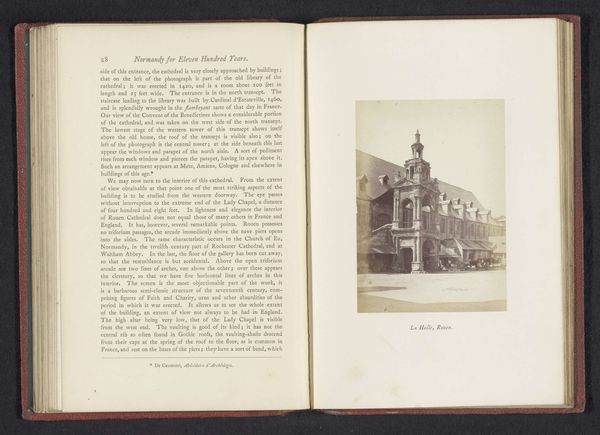

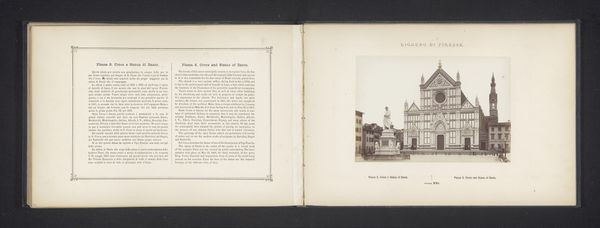

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: height 118 mm, width 90 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

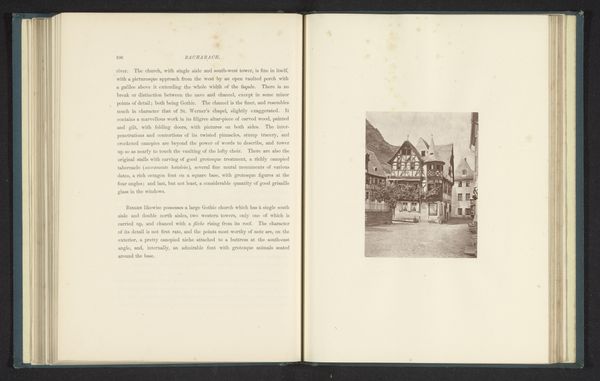

Curator: Looking at this albumen print, titled "Vakwerkhuizen op de markt in Boppard," we see a street view captured by Cundall & Fleming sometime before 1868. It presents a detailed scene of half-timbered houses. What are your initial impressions? Editor: Stark. The monochrome tones, typical of early photography, amplify the structural geometry of the buildings, casting a very formal pall. You know, there's almost an imposing sense of order communicated. Curator: Indeed, the clarity suggests a conscious engagement with architectural detail. Focusing on the socio-economic, it would be fruitful to understand who was producing, consuming, and circulating these photographic prints of urban scenes. Early photography offered an opportunity to document and categorize buildings at scale, right? Editor: Precisely. But for whom? Considering the period and subject matter, I would be asking about class and power structures visible in the architecture— who had access to Boppard’s market square? Whose histories are embedded in those structures, and how might this image uphold or challenge dominant narratives of its time? I’d bet there are untold narratives concerning women, laborers, and minority groups affected by those houses. Curator: Interesting— let’s push further on that material aspect and its related labor— to create these very prints involved sourcing materials, transporting equipment, employing darkroom technicians. By whom? Are we seeing orientalist approaches and their traces within the chosen setting, or maybe it represents a fascination and/or idealization of European medieval building processes. Editor: It could certainly play a role to justify the Orientalist component when presenting idealized past and a narrative linked with notions of progress. Thinking about progress—it might be important also to dig into what market life really was, who it included or excluded... Photography isn't transparent after all, and as photography became democratized later, were the buildings' functions and stories recontextualized, reframed through subsequent capture? How does the reproducibility shift meanings over time? Curator: I agree! Understanding the image’s place in these networks can allow us to challenge the art's history to broader socio-economic and environmental transformations, helping demystify high-art contexts in the end. Editor: I am curious, how we re-use these images and imbue them with renewed or diverging narratives in modern conversations. A deep examination encourages questions regarding social agency to ensure inclusive engagement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.