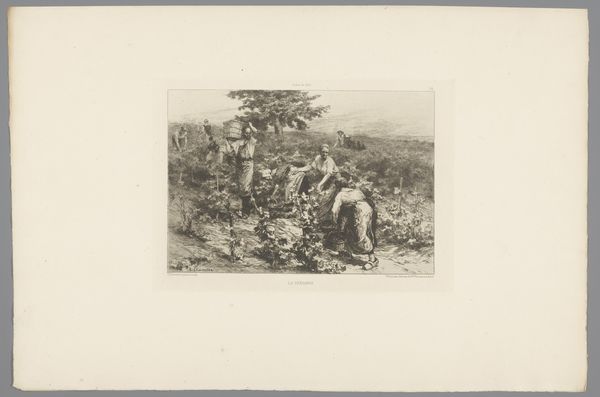

print, etching, plein-air

# print

#

impressionism

#

etching

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

united-states

#

realism

Dimensions: 5 7/8 x 7 7/8 in. (14.92 x 20 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, here we have Julian Alden Weir's "The Farm," created in 1889. It’s an etching, a landscape study done en plein-air, and it’s part of the Minneapolis Institute of Art's collection. What's your first impression? Curator: Faded. Gently faded like an old memory trying to surface. It's so delicate, almost vanishing, yet the basic elements—the trees, the farmhouse—hold their place firmly in the scene. Editor: Yes, and there's a stark contrast with that vanishing aspect. "The Farm" evokes the agrarian experience and poses interesting questions about land ownership and the commodification of rural life at the end of the 19th century, when the rural population faced new economic struggles and farm ownership concentrated among fewer people. Curator: True, but on the other hand, I love the open field and that cluster of trees almost hiding the farmhouse—the romantic idea of nature just swallowing human intrusion. I can feel the stillness of the afternoon sun. Do you think that's intentional, or is my imagination running away with me? Editor: It's both. The Impressionist movement of the period encouraged exactly that kind of romantic ideal, even as it sought to redefine how we represent nature on our own terms and using industrial pigments and industrialized print techniques like the etching we see here. Weir lived and painted during a period of Reconstruction, a cultural period shaped by new class antagonisms and a crisis of the family, and as farms failed in this period, land was becoming privatized more than ever. His work presents us with both an aesthetic fascination of these agrarian spaces and a window into the complicated realities of living in rural America. Curator: Yes! Like a lovely ghost. These tiny strokes carrying a historical punch. What can we learn from seeing history as impression, filtered and fleeting rather than defined like the political narratives of a painting by David, say? Editor: Precisely. Weir’s artistic vision and historical period invite us to ponder these complexities in how we choose to preserve memory. What should remain fixed in our collective consciousness, and what should fade into the quiet landscapes of the past? Curator: A lovely point—and something that stays with you long after you've stepped away from the print.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.