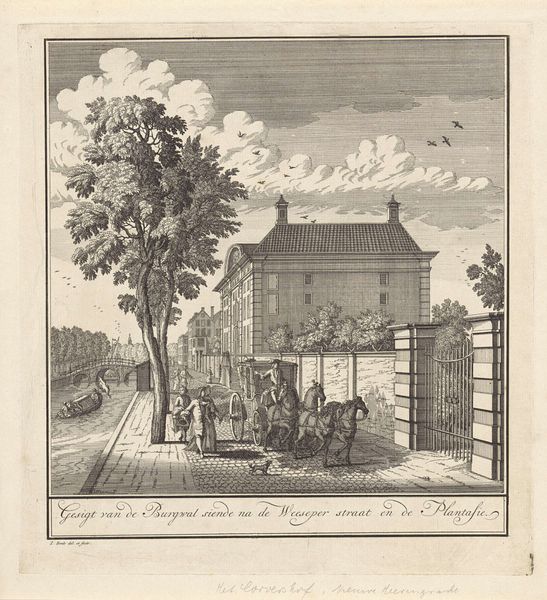

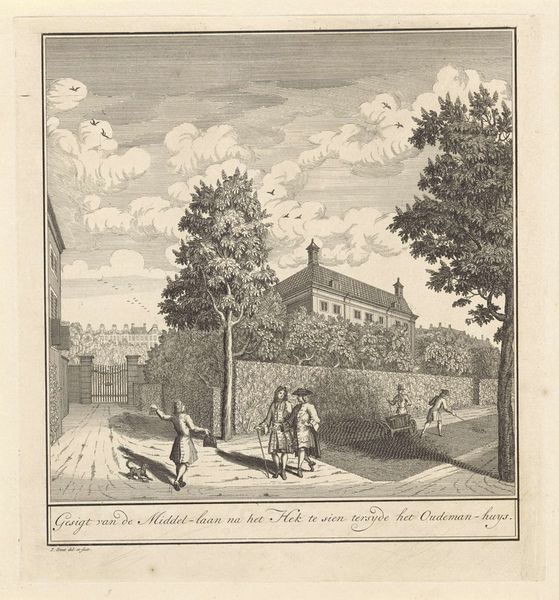

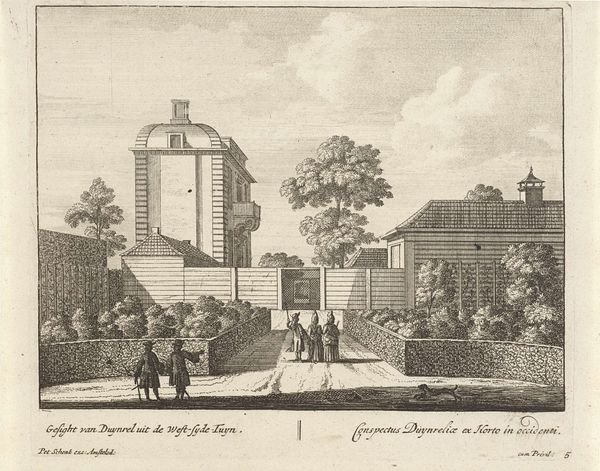

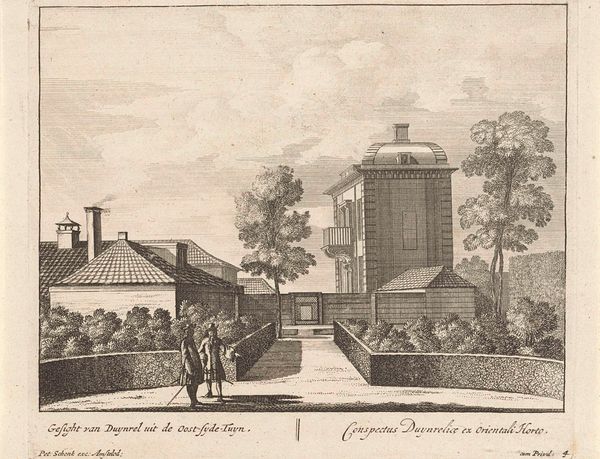

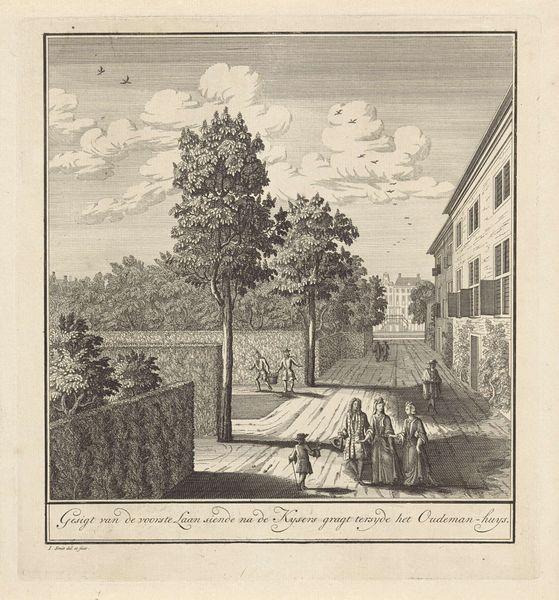

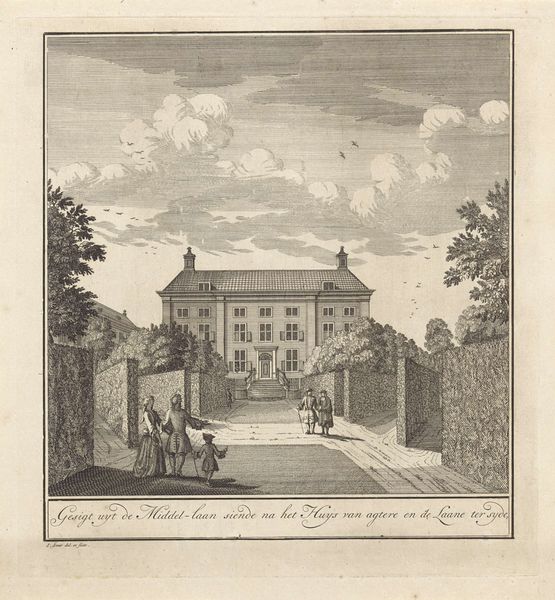

Gezicht op de zijkant en een deel van de tuin van het Corvershof te Amsterdam 1723 - 1748

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

line

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 265 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jan Smit’s print, "View of the Side and Part of the Garden of the Corvershof in Amsterdam," made sometime between 1723 and 1748. The rigid lines give the architecture a feeling of order, yet it seems slightly dreamlike. What draws your eye? Curator: The lines, yes, but consider what the engraving medium tells us. Printmaking allowed for mass production. Who was this image made *for*? Who had access to views of the Corvershof? Consider the labour involved in creating this scene, reproducing it, and disseminating it within the burgeoning commercial markets of 18th-century Amsterdam. Editor: So, it’s less about the building itself and more about the social circulation of its image? Curator: Precisely. Think about the ladders leaning against the wall, the workers moving them. It’s not just an idealized landscape, but a landscape being constructed, maintained, presented for consumption. It implicates us, the viewers, in the process of seeing and possessing this space. What’s being sold here isn’t just a view, but a lifestyle. Editor: That makes me think about how the print medium democratized art viewing in some ways, allowing more people to access images of places and things they might never see in person. Curator: Exactly! And with increased access comes increased consumption, further fueling the cycle of production and desire. Consider also, what is *not* depicted. What are the social realities behind these walls, the conditions of labor that made the Corvershof possible? The print elides these complexities. Editor: That’s a crucial point. So, seeing it not just as a picture, but as a material object deeply embedded in the social and economic structures of its time, reveals a much richer and more complicated story. Curator: Yes. By examining the materiality of the print, we move beyond simple aesthetics and address broader issues of class, consumption, and power. We might question who the workers depicted in the engraving labored for, the role they played, and whether there were depictions made by laborers, as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.