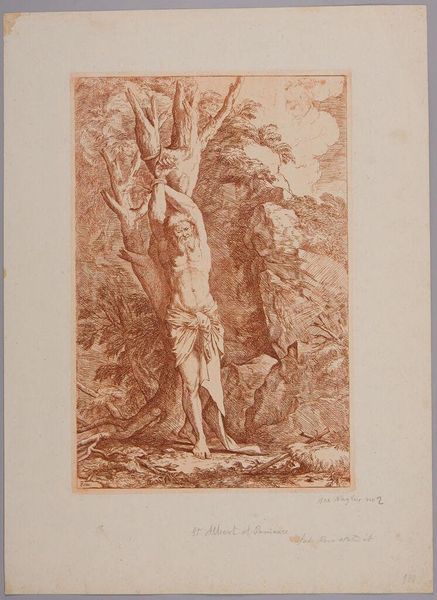

print, etching

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

italy

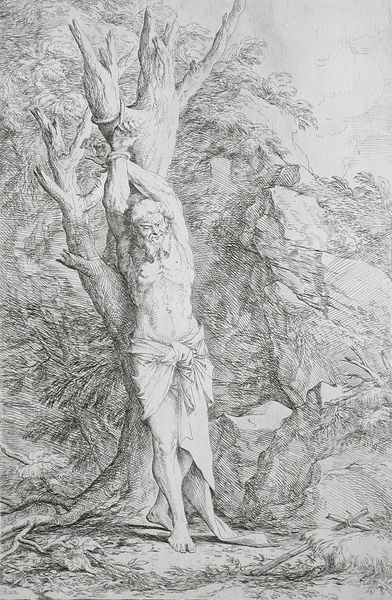

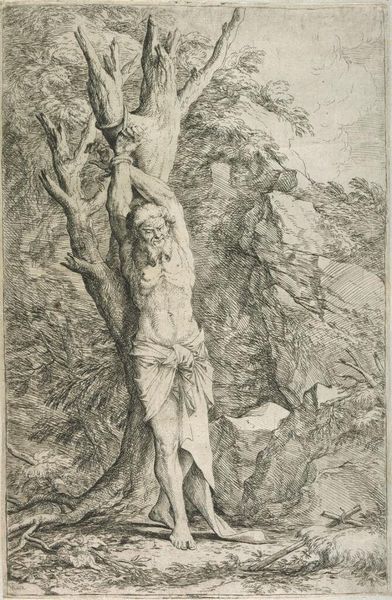

Dimensions: 13 1/2 x 8 13/16 in. (34.29 x 22.38 cm) (plate)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Salvator Rosa’s etching, “Albert,” created around 1662-1663, depicts a partially nude figure bound to a barren tree, set against a rugged landscape. It is currently part of the collection at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: My first impression is one of intense physical suffering. The stark black lines create a feeling of constriction, particularly around the figure’s wrists bound to the tree. The almost skeletal form speaks to a deprivation—almost like a penitent in extremis. Curator: That’s a powerful observation. Consider that Rosa, though celebrated, operated in a heavily stratified artistic landscape. This depiction of a suffering male nude can be interpreted through the lens of marginalized identities and social precarity—linking to debates about power structures prevalent in his time, class struggles perhaps represented through the figure's strained physicality. Editor: Absolutely. And that bare tree is fascinating— almost cruciform. Symbolically, it evokes ideas of sacrifice, the stripping away of worldly comforts. Are we meant to associate the figure of Albert with a type of secular martyrdom? There's an echo here of earlier depictions of figures like Saint Sebastian, similarly bound and suffering. Curator: That is indeed what makes it interesting; that is also because Albert Meynier was actually involved in the plot of taking the king to Lyon along with other important nobles and he was condemned and hung. It might resonate on those ideas of how politics could actually condemn people for it; and in the image, one can read that feeling of grief. Editor: I can totally see it in that light; because to go more thoroughly in how the tree reminds to the cruciform shape, Albert is condemned and the drawing portraits how the power system that he thought he wanted, ended by finishing him. It is also to take in account how men ended hanging from trees to portrait the consequences in the past Curator: Right, these symbols served not merely as aesthetic choices, but as potent visual shorthand understood within the context of the 17th century, to condemn actions. I am more fond into how the use of shadow shows us his despair; its a visual approach that makes the watcher think of its actions, don't you think? Editor: Agreed. Seeing beyond the aesthetic qualities, and engaging with social conditions adds to the meaning this visual record had. Rosa seems to me to use visual language, making it universal and timeless and, beyond it all, something to meditate of.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.