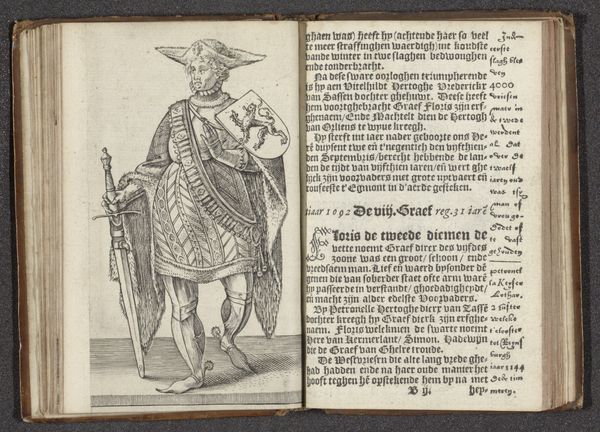

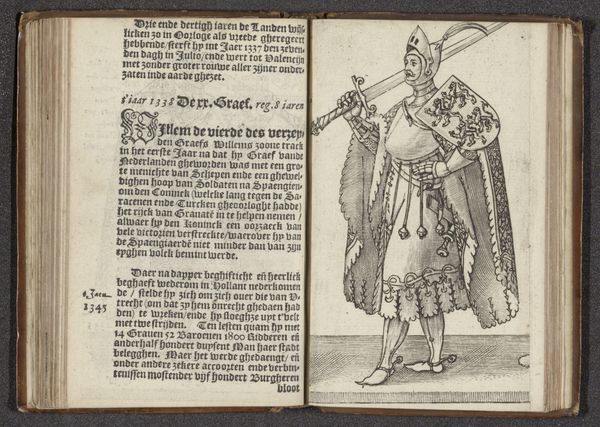

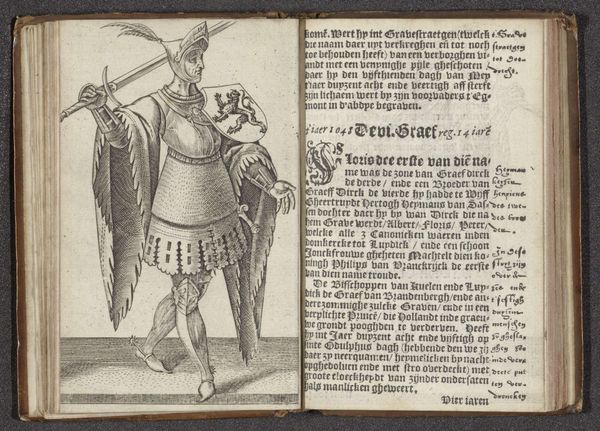

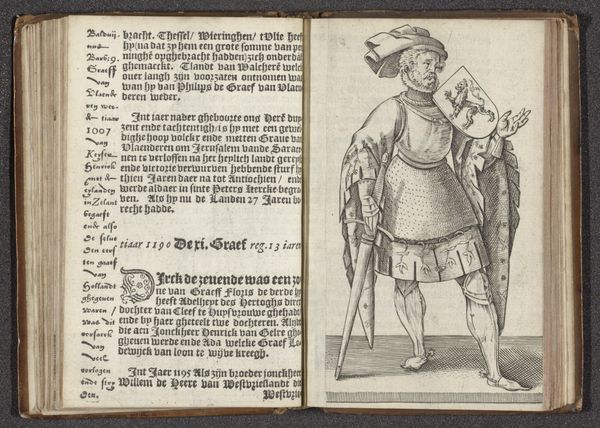

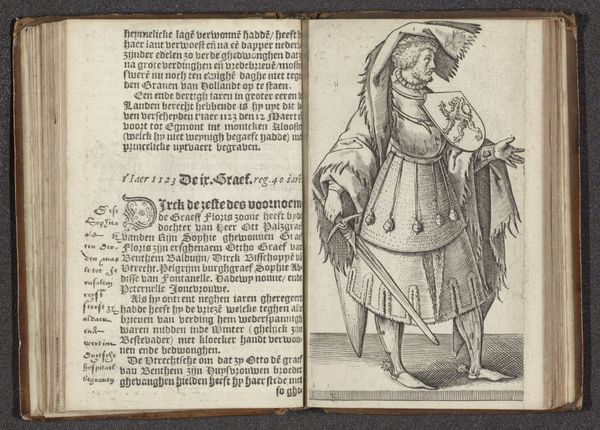

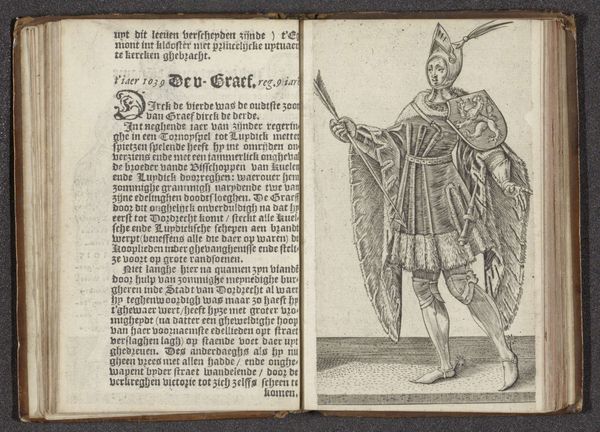

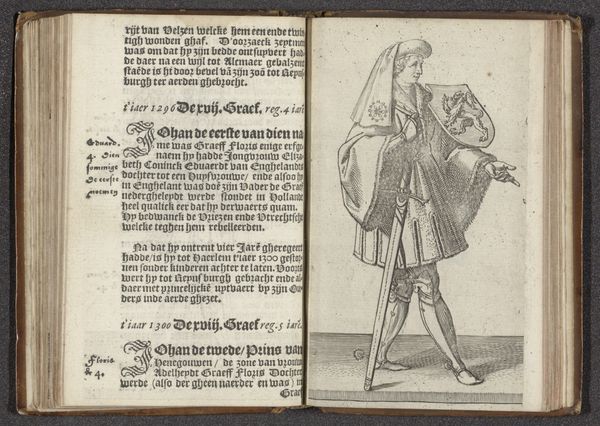

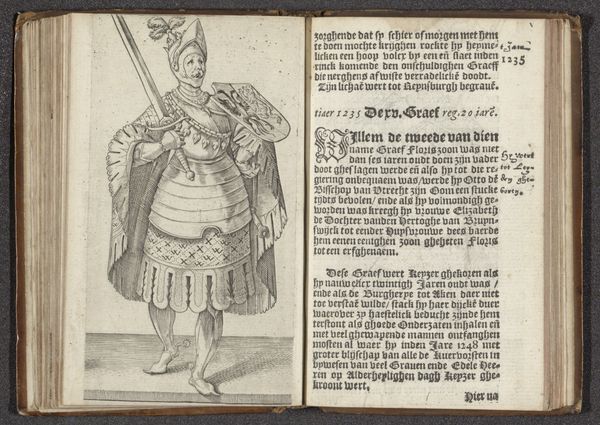

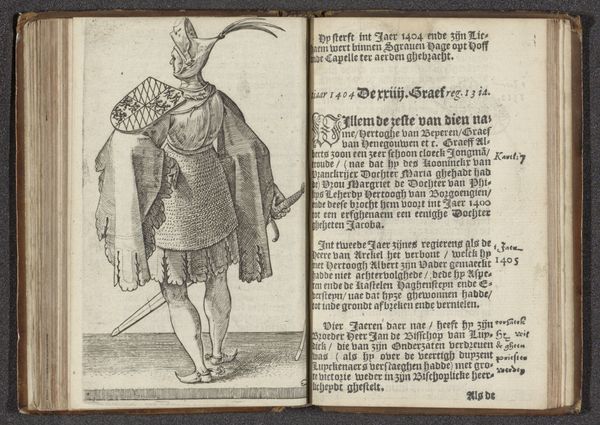

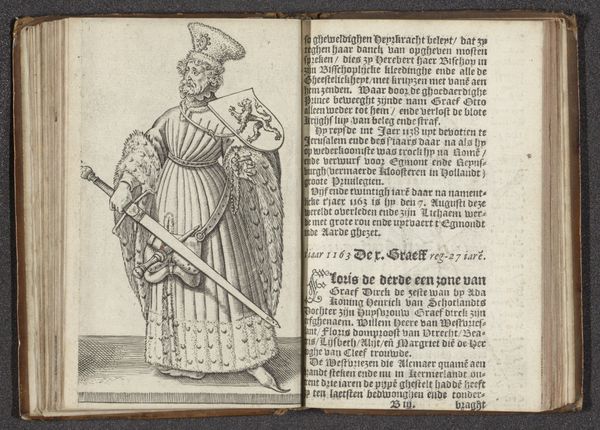

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

coloured pencil

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 85 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s dive into this engraving of "Graaf Floris IV van Holland" by Hendrick Goltzius, made around 1586-1587. It's a fascinating example of Northern Renaissance portraiture, now housed at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's interesting! I'm struck by the detailed lines that make up the figure, and also by how much text surrounds the image. How should we read this image now, centuries later? Curator: Let’s start with the materials themselves. Goltzius chose engraving, a printmaking method. Consider the labor involved in creating those precise lines with a burin. Each mark required skilled manual work. How does this focus on labor influence how we think about portraiture in the 16th century? Is it simply about depicting likeness, or does the process itself add another layer? Editor: That's a great point. I hadn't thought about the act of making as part of the meaning. It seems so different from painting, where the artist's hand is more directly visible. This feels…more removed. More industrial, maybe? Curator: Exactly! And think about the social context. Prints were reproducible. How did this affect the dissemination of images and the accessibility of portraiture? Was it about democratizing representation or about creating a new kind of visual commodity? Consider what it meant to reproduce power this way. Does mass production challenge traditional views of high art, where uniqueness is often valued? Editor: So, the engraving itself becomes part of the story. It isn’t just *of* Floris, but about the means through which he’s made visible and circulated. It is about who *owns* his image. I guess it forces you to see it as a manufactured representation. Curator: Precisely! We begin to see that portraiture isn't only about the subject, but the whole system that creates and distributes their image, its materiality, and its socio-economic implications. The very ink on the page is a result of labor, trade, and technologies of the period. This forces us to reckon with those complex networks and processes embedded within what appears, at first glance, to be a straightforward portrait. Editor: I see, thanks! I definitely have a broader appreciation of the image now! It's a reminder to look beyond the surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.