print, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

caricature

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

genre-painting

#

nude

#

erotic-art

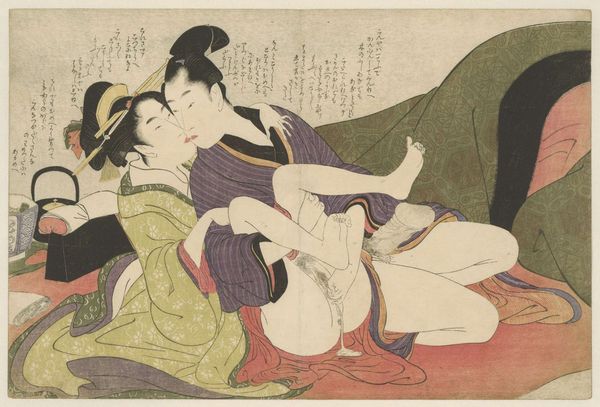

Dimensions: height 253 mm, width 383 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

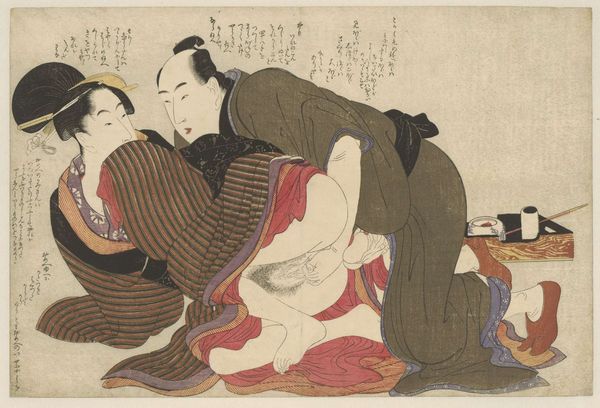

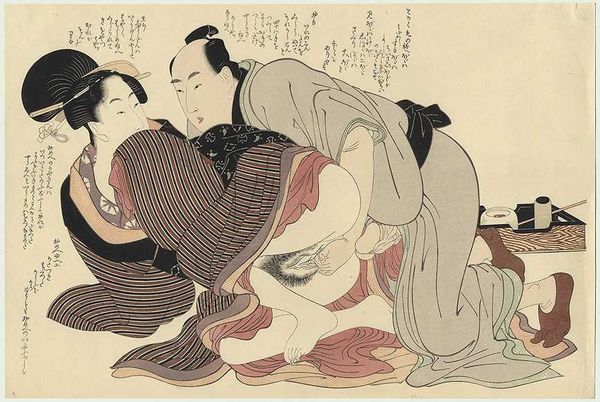

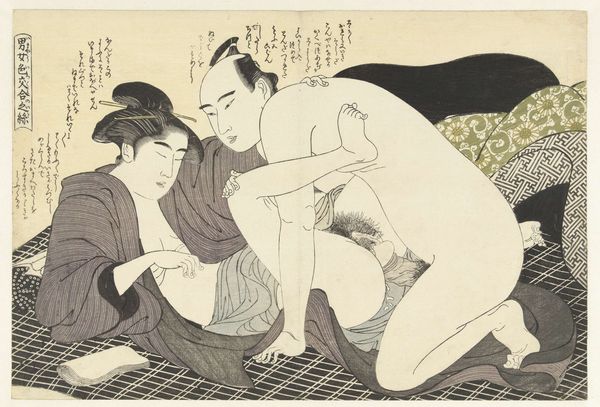

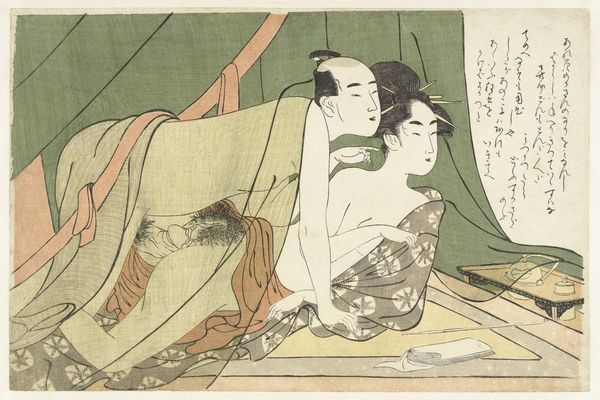

Curator: Ah, yes. Here we have Kitagawa Utamaro's "Married Man and Widow," created around 1799. This sensual scene is a woodblock print, a true gem of the ukiyo-e tradition, now housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Well, it’s certainly… intimate. The composition is rather crowded, but there's an undeniable emphasis on the act itself, presented with a somewhat stark realism. It really zeroes in on bodies, textiles and their arrangement. Curator: Ukiyo-e prints weren't just decorative; they offered a glimpse into the pleasure quarters, challenging social mores and gender norms, albeit within specific power dynamics. Considering this in its socio-political context we should consider its original audiences. It surely sparked conversations about female agency and sexuality in ways previously unexplored in art accessible to wider audiences. Editor: Agreed. These prints were products for mass consumption in Edo period Japan, not simply innocent artworks, nor explicitly created for discourse regarding equality. Look at the man’s elaborate clothing contrasted with the stark nakedness being pushed to the forefront, or at the domestic items in the background. What were the labor conditions required to create all these items, and for whom were the created? Curator: I see your point. It's crucial to dissect the power structures embedded within these portrayals of intimacy. While offering a glimpse into female desire, were they simultaneously reinforcing patriarchal gaze and commodification? That must remain part of our consideration. Editor: Exactly. This print makes me think about the system in which beauty itself was constructed and commercialized. It challenges any straightforward reading of freedom or liberation. Curator: It's a stark reminder of how entangled pleasure, power, and production can be. Utamaro's skill isn’t just in the exquisite lines and vibrant colours; it's also in provoking a complex interplay of desire, economics and morality for the original audience and our interpretation centuries later. Editor: Indeed. Viewing art like this today demands a nuanced lens, recognizing it not only as a snapshot of history, but as a manufactured object that speaks volumes about its culture and its people, from the artist, the producer, the owners to the observed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.