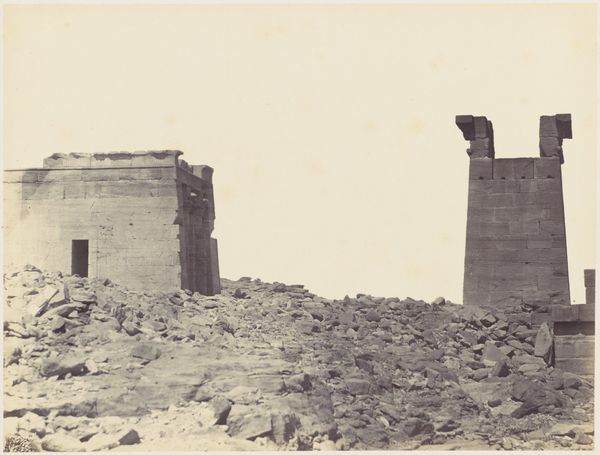

photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

landscape

#

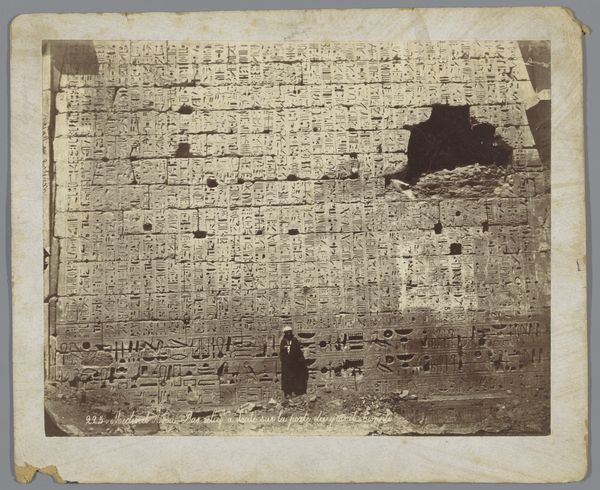

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

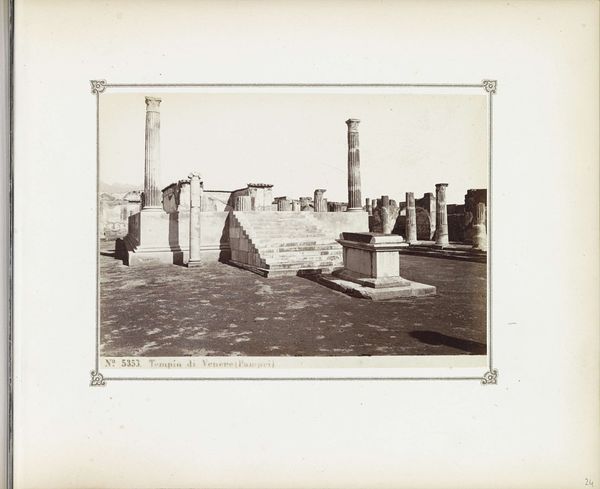

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

architecture

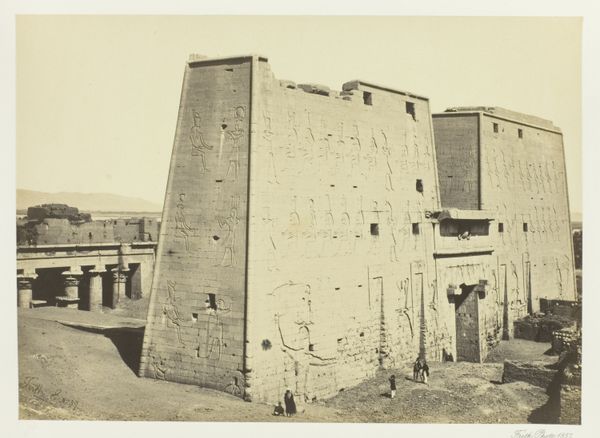

Dimensions: height 217 mm, width 276 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have “Pyloon met obelisk in Luxor,” a gelatin-silver print dating from around 1870-1890, made by C. & G. Zangaki and held at the Rijksmuseum. I’m really drawn to the textural qualities, you know, how the light interacts with the rough surface of the stone. What jumps out at you when you see this photograph? Curator: What I see is not simply an image of an obelisk and pylon, but a document of material transformation. Look at the hand of labour, the processes involved in quarrying the stone, transporting it, carving the hieroglyphs – each a testament to human effort. What materials are prioritized and for whom is also interesting. Editor: I see what you mean. It makes me consider the contrast between the permanence of the stone and the...fragility, almost, of the photographic process used to capture it. How does the choice of photography as a medium impact our understanding of ancient Egyptian civilization? Curator: Exactly. Photography, then a relatively new technology, becomes a tool for Westerners to capture and, in a sense, consume Egyptian history and culture. Consider the role of the Zangaki brothers – who were Greek not Egyptian, and sold this photo to Europeans and other Westerners: the relationship to labor is not just in the stone, but also their process and market for these objects.. This image becomes a commodity, part of the broader orientalist project, transforming even ancient monuments into resources for European and American markets. Editor: So, it’s less about the artistic intention and more about the socio-economic conditions that enabled this image to be created and disseminated? Curator: Precisely. We have to ask: whose story is being told, and what materials and processes enabled that telling? The image itself is the residue of a complex network of production and consumption. How does viewing it with that perspective change how you see the image now? Editor: It's a fascinating, and frankly, unsettling shift. It’s less about the grandeur of the obelisk and more about the global dynamics at play in even creating the image in the first place. Curator: Indeed. Material analysis invites us to examine the art in a critical light, not only as aesthetic objects, but as cultural artifacts deeply embedded within historical processes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.