drawing, ink, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

comic strip sketch

#

imaginative character sketch

#

quirky sketch

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

horse

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

genre-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

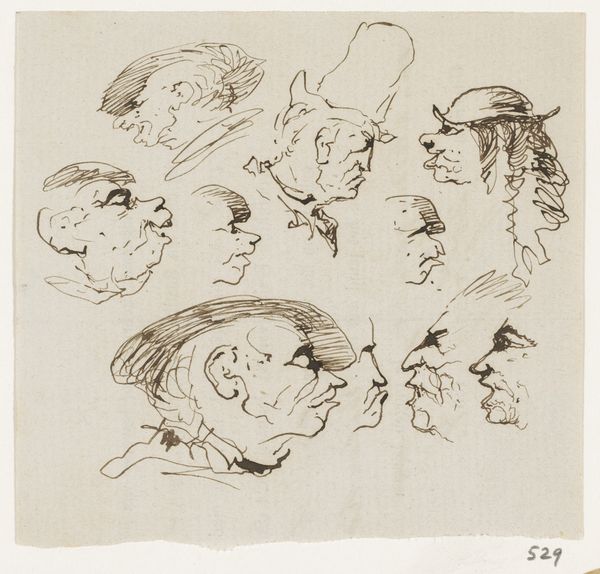

Dimensions: height 81 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I find this study, "Koppen en paarden" or "Heads and Horses," likely from sometime between 1840 and 1880, by Johannes Tavenraat, quite intriguing. Editor: Yes, the first thing that strikes me is the dynamism of the ink. Each face, each horse, rendered with such a sense of fleeting observation. Curator: Indeed, but these aren’t merely studies in form. Tavenraat was working in a period grappling with burgeoning industrialization and social upheaval. These caricatured heads, their expressions ranging from grim to grotesque, might well represent the anxieties of a society in transition. Consider the asymmetrical features of the upper right head. Is that anxiety embodied there, a fear of the future reflected in that single form? Editor: Perhaps. However, I see the distortions more as formal experimentations. Look at the use of line weight, the strategic hatching to create shadow and volume. Semiotically, those deliberate choices structure our perception. They pull us into the work’s intrinsic pictorial logic first, before we overlay sociopolitical interpretations. I find in Tavenraat’s method echoes of neoclassicism, even here. Curator: Yet we can't ignore the socio-cultural forces always at play. The relatively scarce representations of the laboring classes in fine art, and the contexts in which such representations are done, for instance. Tavenraat had been a student of landscape and animal painter, Albertus Brondgeest. Do these caricatures mirror prevailing stereotypes or challenge them? To interpret them fully, we have to acknowledge prevailing biases, and assumptions of gender, class, and even speciesism during that period. Editor: Of course, context is crucial, yet so too is visual autonomy. The stark whiteness of the paper and limited tonal range draws attention to the artist's hand—the application and variation of line. Curator: The rawness of the medium then also communicates a particular idea about society at the time, perhaps as broken, flawed or chaotic, reflecting an artistic desire to push against an idealized reality of the 19th Century. Editor: I see how you can read it that way. To me, though, it serves more to isolate the study into a space where formal properties become its key attribute, so the artist might discover something new through structure alone. Curator: Thank you, that fresh analysis invites new insights to better examine artistic representations of race and identity. Editor: It's fascinating to think how differently we perceive an artwork's character through distinct analytical lenses.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.