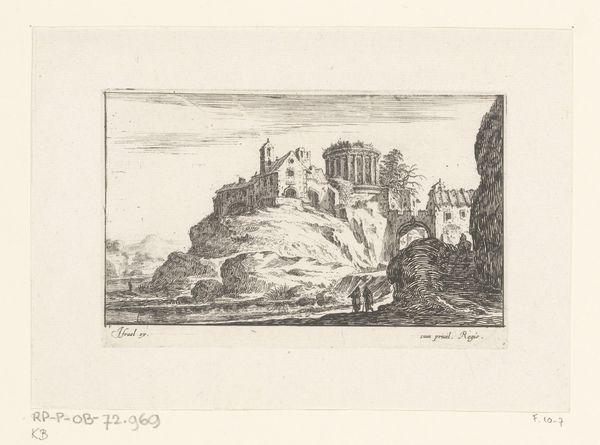

print, metal, etching, engraving

# print

#

metal

#

etching

#

landscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 70 mm, width 103 mm, height 95 mm, width 129 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Étienne Bosch’s “Ruïne Rome,” a print created before 1931 using etching and engraving techniques on metal. It gives a real sense of the weight and history of the subject. What strikes you most about this piece? Curator: The artist's choice of etching and engraving to depict Rome's ruins immediately draws my attention to the means of production. Look at how these labor-intensive processes translate the decay into physical lines. This contrasts with painting, a quicker form, doesn’t it? What do you make of this opposition? Editor: That's a fascinating point! It's almost like the process mirrors the slow, erosive forces acting on the ruins themselves. Does the use of metal plates in printing, a fairly reproducible medium, somehow democratize the ownership or experience of these ruins? Curator: Exactly! Think about the availability of such prints versus, say, commissioning a unique painting. The multiple exists due to its material process; hence, making it attainable across societal strata, democratizing the image of Roman ruins, if you will. In the historical context, where would an image like this be sold? Editor: Maybe in print shops, or perhaps as souvenirs for travelers? They would bring Rome to those who couldn't afford to journey there. Curator: Precisely. This commodification speaks volumes about art consumption. And how labor, even that of the artist, feeds into these markets. What does that leave you wondering about? Editor: This really highlights the artist's role not just as a creator but also as a worker within a system of production and consumption. I never really considered how much the materiality informs accessibility. Curator: Agreed! Examining art through its materials and production methods opens a richer understanding. The how of art is, at times, just as critical as the what.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.