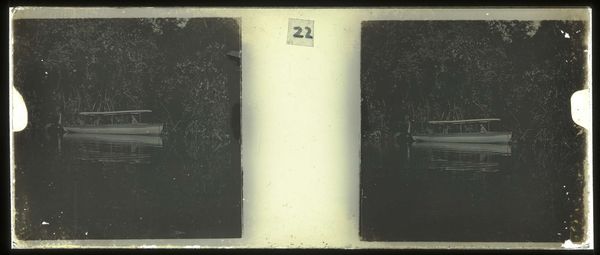

photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

realism

Dimensions: height 4.5 cm, width 10.5 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a wonderfully evocative photograph. This is "Plantage Accaribo" by Theodoor Brouwers, dating from somewhere between 1913 and 1930. It's currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. What’s your immediate take? Editor: Overwhelming density. The black and white exaggerates the darkness of the jungle and evokes a real sense of oppression, as if it's swallowing the figures. Curator: I see what you mean. Brouwers worked during a period when Dutch colonialism was at its peak. His photography gives us a glimpse into these plantation economies. How do you think the plantation context is informing your reading of its oppressive qualities? Editor: Plantations became grounds of major ecological disruption, completely restructuring ecosystems and labor dynamics. That dense background you mentioned— it almost becomes a visual metaphor for colonial expansion and extraction, overwhelming native populations. Curator: Precisely, and this particular image shows the landscape and perhaps also hints at those labor practices with the figures, a poignant commentary, even if unintended. The image makes one wonder who are the men, are they working? Are they supervisors, just passing through? Editor: I wonder too if their almost faceless appearance suggests a symbolic dehumanization, maybe echoing some aspect of colonial management techniques. How power diminishes individuality… Curator: That reading makes sense when contextualizing such imagery in art and photography history. While seemingly just a landscape photo, it triggers complex reflections on colonialism’s impact, even if it's rendered with realist techniques. Editor: The “realism” lends it a disquieting sense of immediacy. This is not some romantic vision of exotic lands but, you are right, something perhaps more problematic. Curator: Photography freezes time and captures details. In a way, “Plantage Accaribo” allows us a glimpse into how photographic techniques were intertwined with colonialism, shaping our perceptions and potentially revealing some less examined sides. Editor: Thinking about how museums collect and display such pieces also forces me to consider whose perspective is usually prioritized when these narratives are told, and if we, as observers, also carry this burden with us. Curator: It's these multi-layered contexts which keep drawing me to study of symbols and historical continuities. What may appear as a straightforward visual record reveals deeper socio-political complexities about humans, environments and more… Editor: Absolutely. Art like this continually challenges viewers, making us interrogate histories, power dynamics and our place within them as historical beings and art patrons too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.