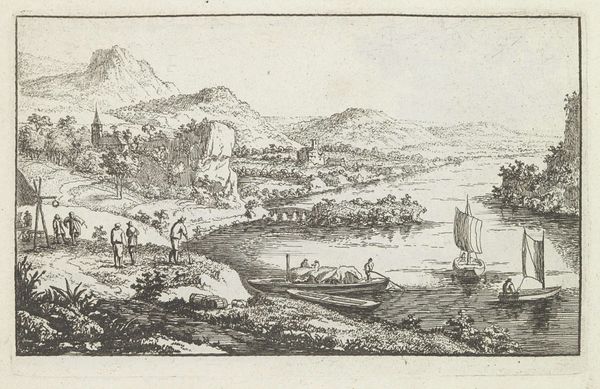

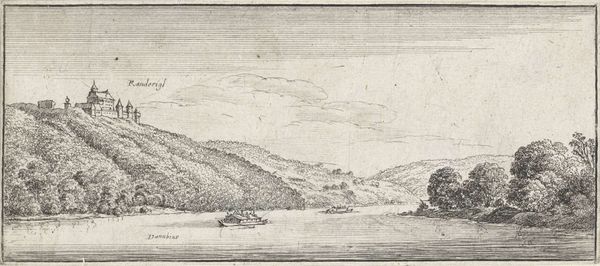

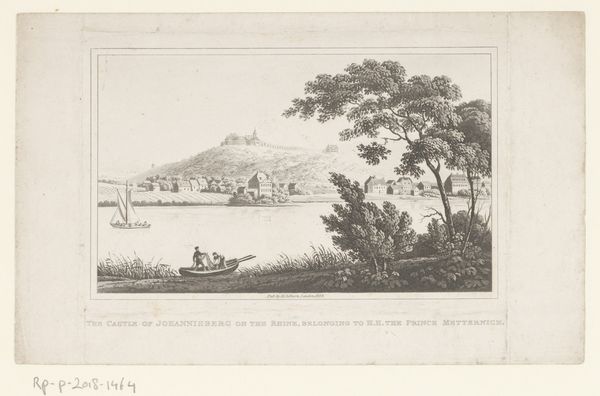

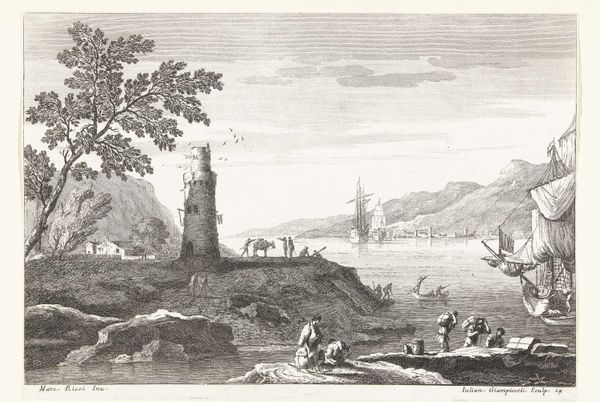

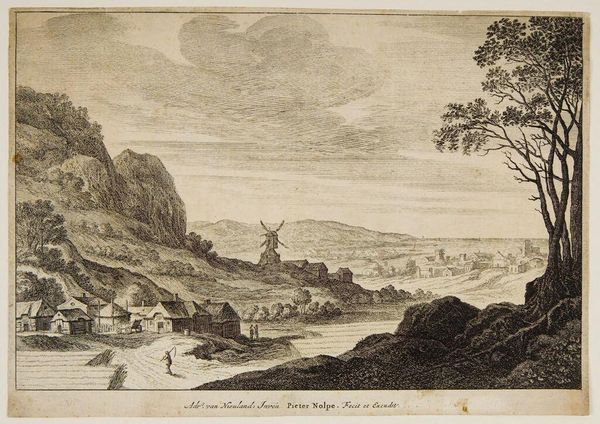

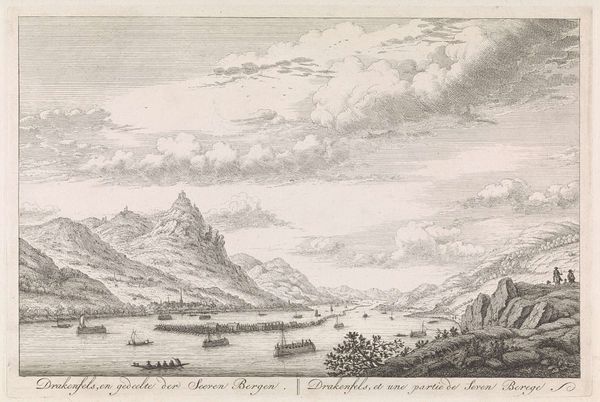

print, engraving

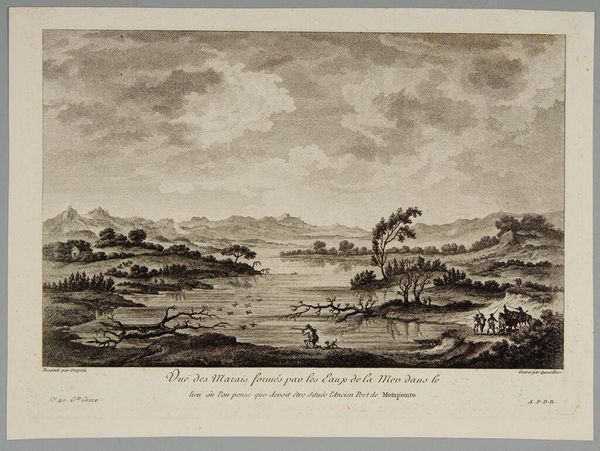

#

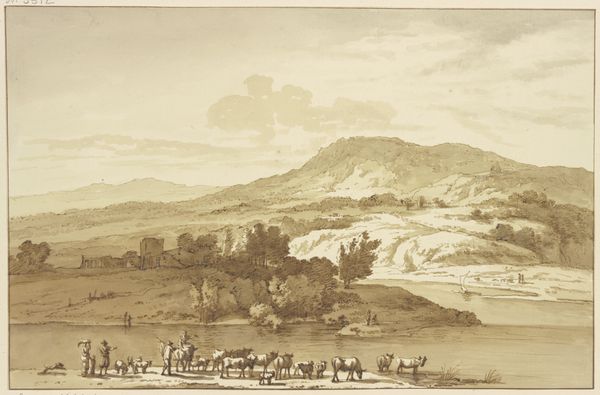

toned paper

#

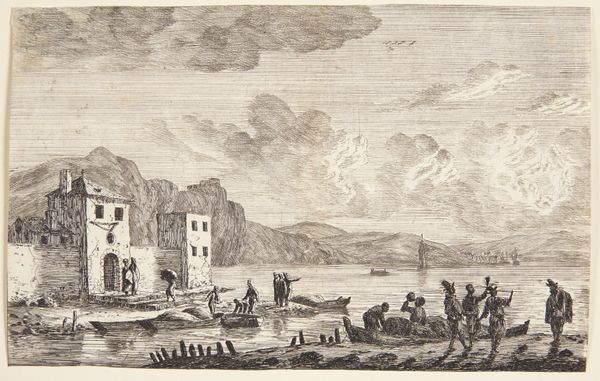

baroque

# print

#

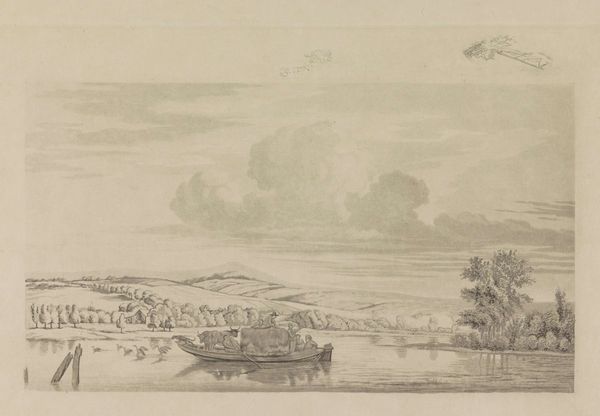

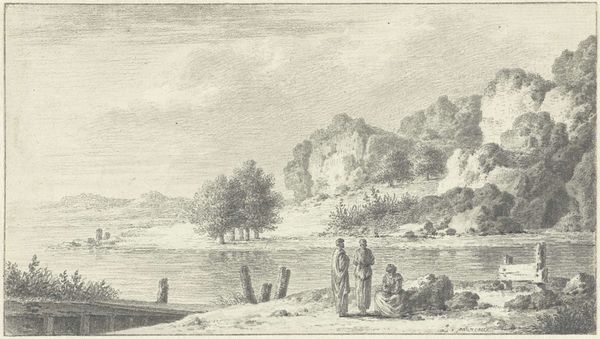

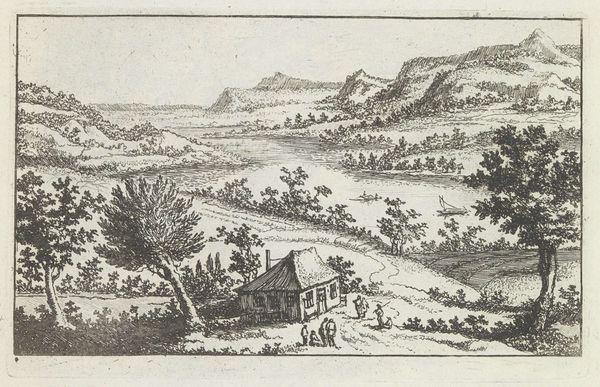

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

river

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 57 mm, width 134 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Gosh, it reminds me of those old postcards, doesn’t it? Something about the delicate lines and the monochrome gives it that vintage charm. It's almost as if the paper itself holds stories. Editor: Indeed. What we're looking at is "Landscape with a View of Sebins on the Danube," created between 1625 and 1677 by Wenceslaus Hollar. Housed here at the Rijksmuseum, it’s a beautiful example of Baroque landscape printmaking. Curator: Baroque landscapes, to me, always have this underlying drama, even in stillness. Look at how the little boat cuts through the vast expanse of water—you immediately get a sense of the world being larger than you are. But, it feels kind of intimate. Editor: That sense of scale is certainly intended. Hollar was working within a burgeoning print market. Views like this, of castles and towns, fed a desire for topographical accuracy but also a hunger for experiencing far-off places through imagery. The cityscape theme satisfied both needs, a public role for art linked to the political power it depicted. Curator: Do you think Hollar was aiming for an 'objective' rendering, or something more poetic? The way the light dances on the water, that seems so full of feeling for me, despite being quite graphic. Editor: I think both. Hollar had the skill to be objective, capturing details, but it was ultimately tied to a system that promoted certain idealized views of cities and power. That picturesque composition is quite intentional, and he created various prints showing similar settings. It speaks volumes about the public's aspiration to see these majestic places. Curator: It really speaks to me about longing for escape. Imagine catching that boat out of town with no responsibilities. What kind of social undercurrent was pushing and pulling in 17th century society? Was there a sense of longing to escape? I wish I had a tiny boat like that. Editor: Without a doubt. Hollar worked during a time of tremendous social and political change. Landscape imagery became increasingly tied to national identity and expressions of power. Prints like these were instrumental in creating a shared sense of place, reinforcing ideas about nationhood. Curator: It gives one pause about how deeply imagery impacts and is impactful to social and personal consciousness, doesn’t it? Editor: It really does. Something so delicate can tell us so much about how the world has changed – and how it hasn't.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.