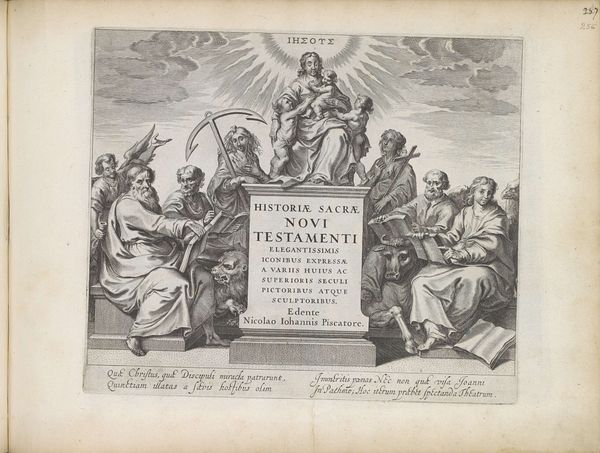

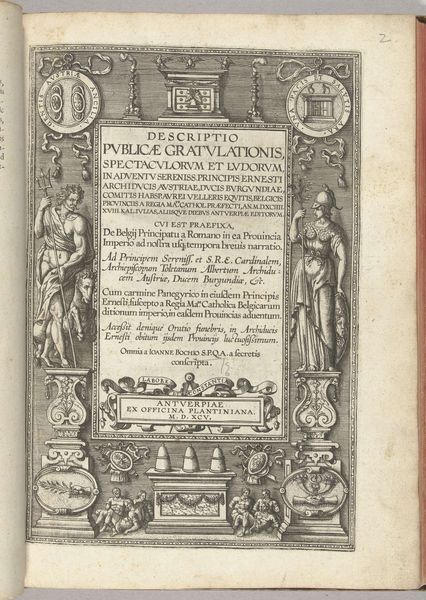

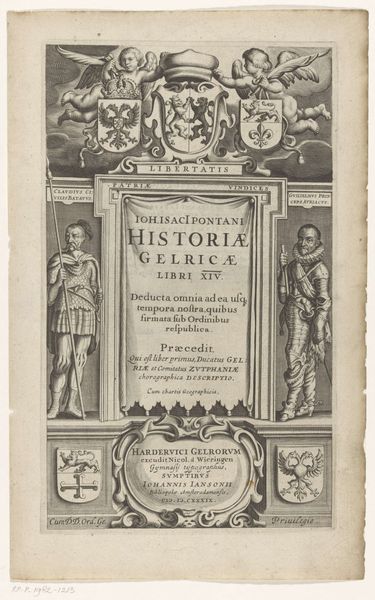

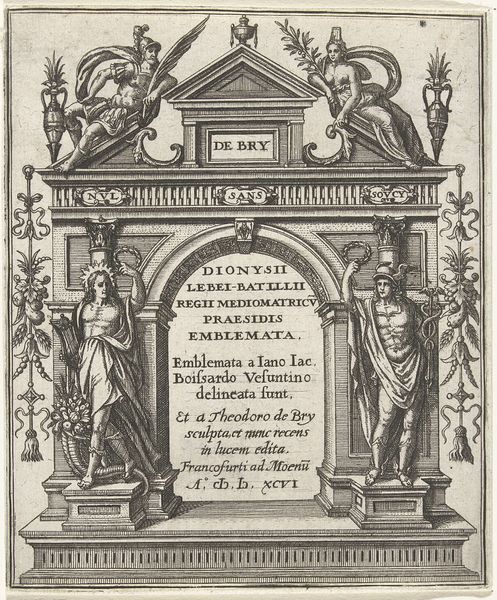

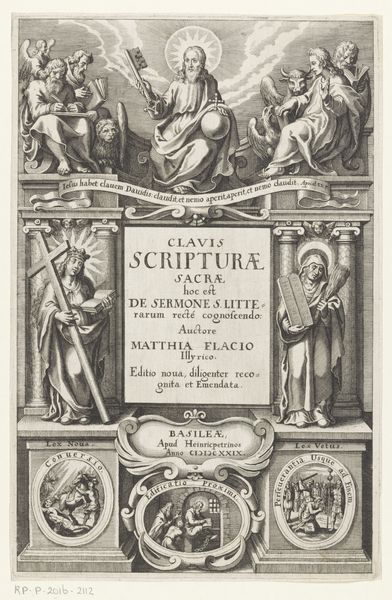

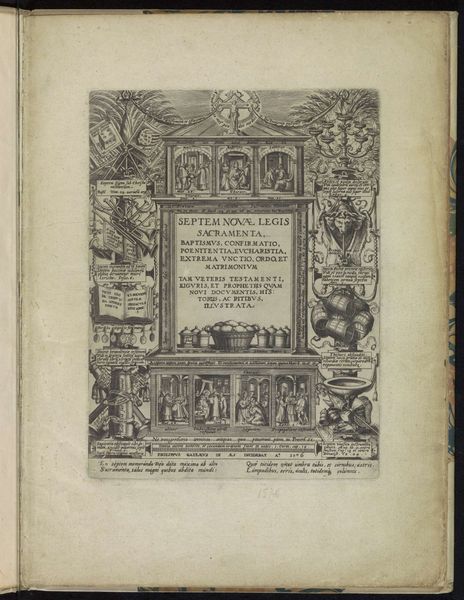

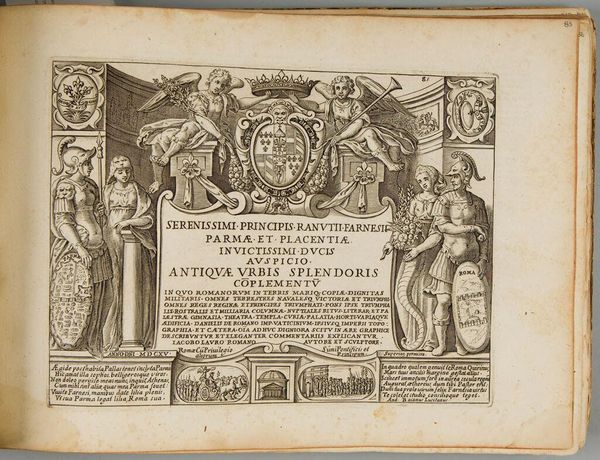

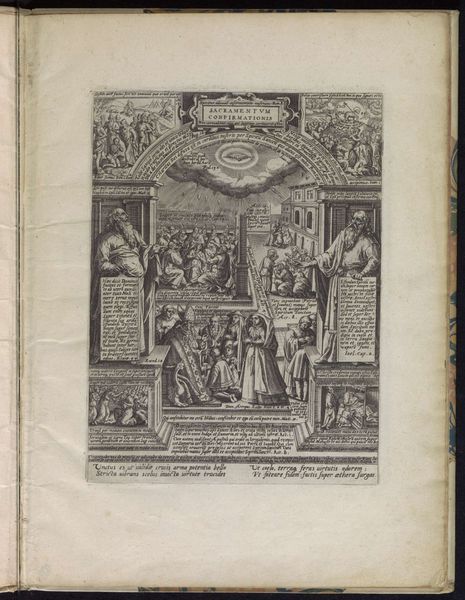

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 7 9/16 × 5 1/8 in. (19.2 × 13 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

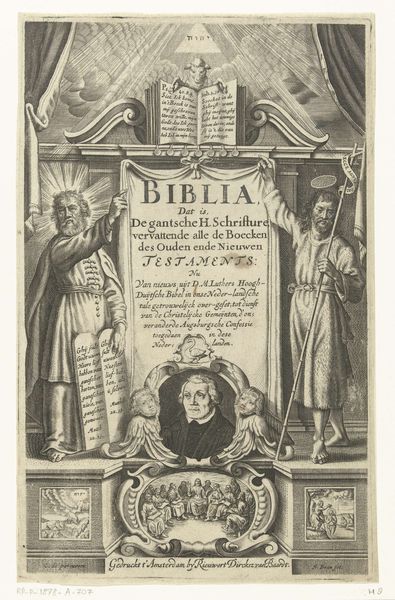

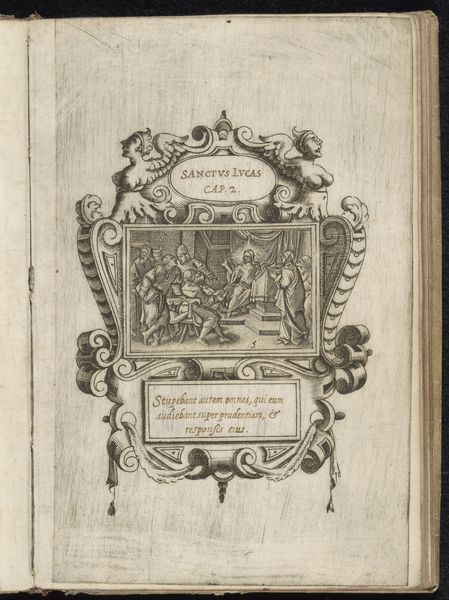

Curator: Here we have "Diodati. Pious Annotations," an engraving dating back to 1648 by Wenceslaus Hollar, currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What strikes you most about it? Editor: It has such a stern, academic feel to it. The density of the engraving, combined with those classical figures, presents a real sense of established authority and maybe even exclusion. Who was this made for, do you think? Curator: Absolutely, it’s dripping with the visual language of authority. This is a title page for John Diodati’s annotations on the Holy Bible, intended to solidify his interpretation and standing within theological circles. Notice the two figures flanking the text, Moses with the tablets of law, on one side, and, I think, possibly Aaron on the other, both representative of scriptural authority. Editor: And their placement is key. They visually frame the words, almost guarding them. The cherubic figures and Old Testament scenes nestled around them feel like justifications, or proof texts almost. What power dynamics were at play here with interpretations and printing during this era? Was access widespread or exclusive? Curator: Printing was becoming more widespread, yet access to interpretations like Diodati's would still have been relatively restricted to educated elites, shaping religious and political discourse in specific ways. His work served to solidify a certain understanding, but also undoubtedly met with contestation from differing religious perspectives. Note that there are Hebrew characters at the very top center—another nod to authority. Editor: The very materiality speaks of power then—the control over not just content, but also access. This piece really makes one consider whose voices get amplified through art and scholarly work, and who remains marginalized in the narrative. Sobering thoughts when gazing upon such ornate religious ornamentation. Curator: Precisely, seeing those biblical figures, now, they speak less to me of a holy history and more to a cultural moment caught in its own carefully constructed image. Editor: It’s a reminder that even devout, religious works can’t be extracted from the broader struggles over intellectual and social power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.