drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

paper

#

ink

#

pen

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

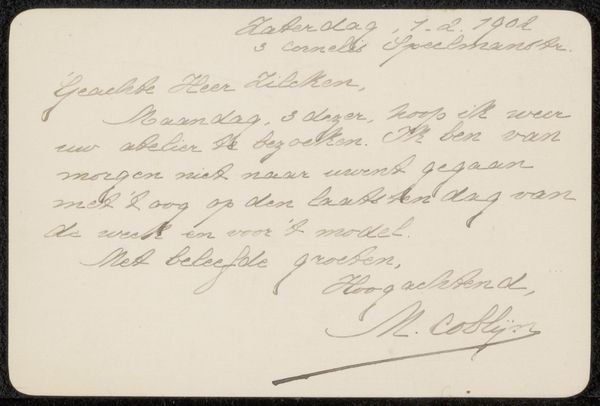

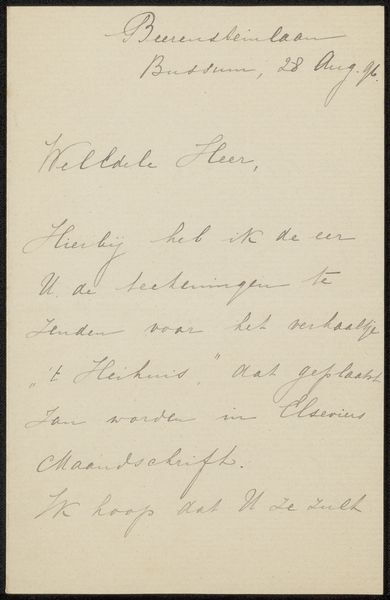

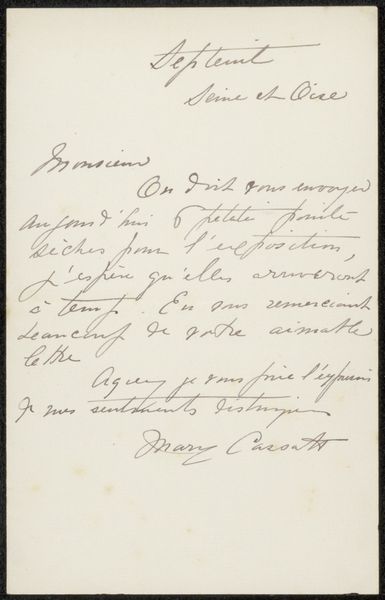

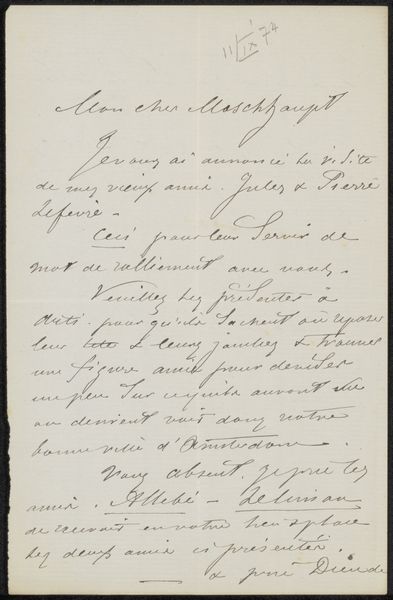

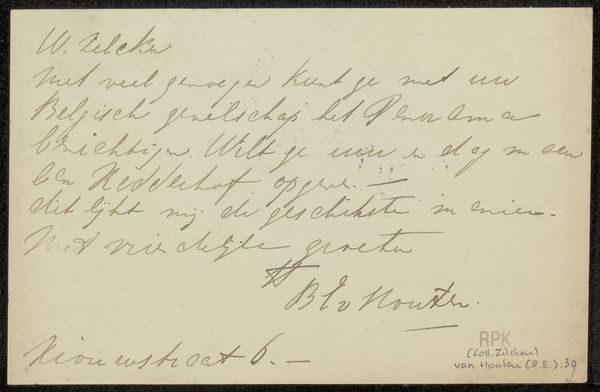

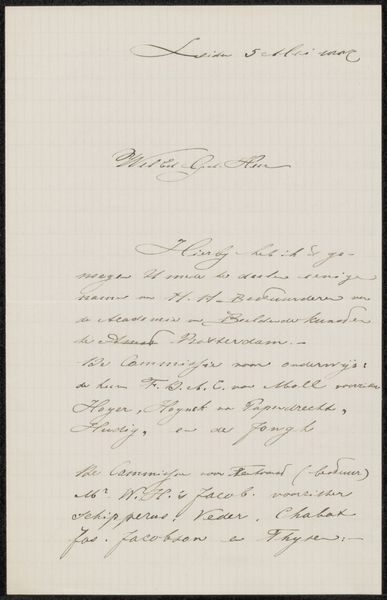

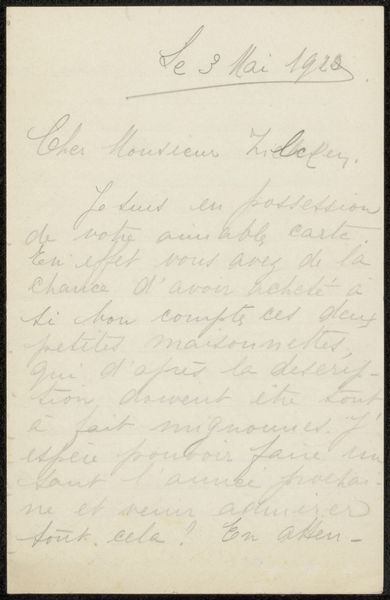

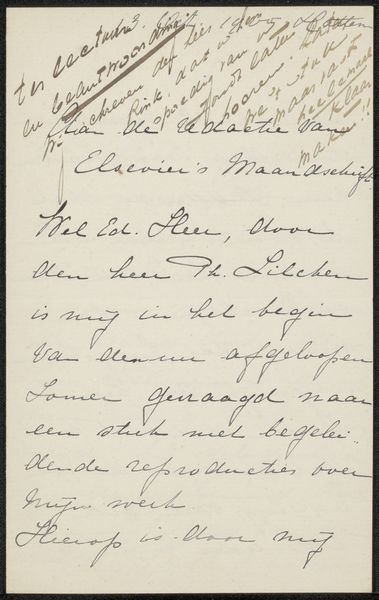

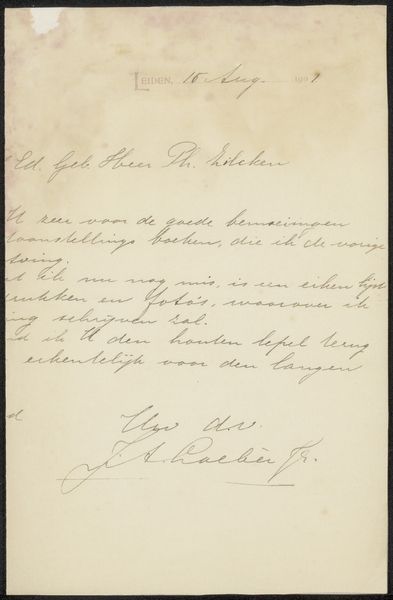

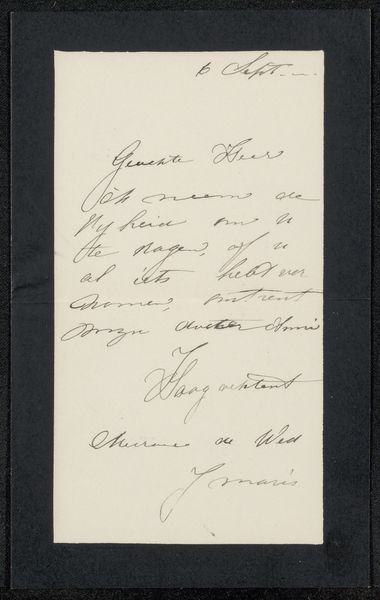

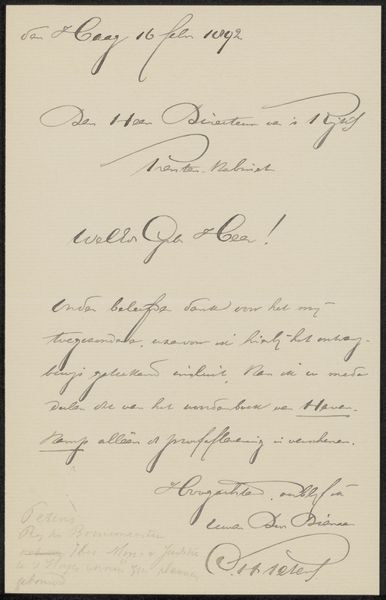

Curator: Here, we have a letter titled "Brief aan Philip Zilcken," penned in 1892 by Gesine Schenck, crafted with ink on paper. The drawing employs pen to achieve a striking and expressive style. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by its intimate nature, the delicacy of the cursive and how it invites a sense of close-up, quiet consideration. It speaks of secrets whispered across time. Curator: Absolutely. Knowing Gesine Schenck, the gendered aspects of written correspondence at the time, the politics around literacy, voice, and representation come into play. It invites the listener to reflect on who has had the power to be heard, and how, throughout history. Editor: The graceful loops and carefully formed letters also bring to mind notions of craft and self-presentation through written language. Considering this a portrait reveals the intention of conveying something deeply personal. It's a reflection of not just information, but of character through penmanship. We’re observing Schenck observing herself in this moment. Curator: You've pointed out the nuanced role of handwriting beautifully. The use of a pen underscores the embodied act of communication. Considering Schenck's position in society, we might consider how the seemingly simple act of writing was, at its heart, deeply tied to freedom, gendered expectations, and privilege. The act becomes profoundly political. Editor: Indeed, looking closely, I note flourishes, intentional artistic elements within a functional form. It gives an intriguing insight into Schenck’s mindset at the time, using handwriting as a tool to subtly but significantly impart a vision of self. Curator: A fitting notion, because when viewed through the lens of social dynamics, we can now consider not just the content of the letter but its presence as a powerful, perhaps quietly defiant, mode of expression. Editor: So true, seeing the act of writing not just as the transcription of words, but a crafted representation. I'm seeing many subtle meanings intertwined here, with far-reaching echoes in modern sensibilities about voice, representation, and identity. Curator: It is compelling to contemplate what the act of physically creating this letter meant, not just to Schenck herself, but what such correspondence represented, and for whom, during a very specific and politicized era. Editor: Indeed, and hopefully it might invite a dialogue about our own assumptions and methods of self-expression today, versus a world of imposed standards or rigid conventions from which some needed to find alternative channels of expression.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.