photography

#

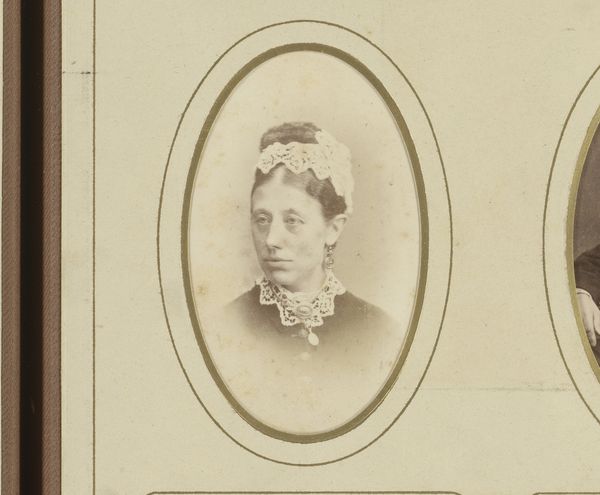

portrait

#

photography

Dimensions: height 87 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This photographic portrait, created sometime between 1895 and 1908 by E. v.d. Kerkhoff, gives us a glimpse into the material culture and image-making practices of the late 19th century. It is currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's such a wistful quality to this photograph. The way the light falls, it’s almost as if she's peering out from a half-forgotten dream. Do you feel that? A soft kind of sadness? Curator: Indeed. The tonal range is quite limited, owing perhaps to the photographic processes of the era, or maybe some later interventions. It would be interesting to consider the production techniques of that period, especially who held economic control within this image’s creation. What would this mean in the cultural and historical context? Editor: Right, what about who made the chemicals, who owned the studios... But before we get too far down that rabbit hole, let's come back to this woman’s gaze. It's so direct, yet it hides so much. Is it longing, acceptance, or just plain weariness that we're seeing in her face? I keep imagining stories for her life. Curator: As a materialist, I see the social dynamics inscribed on her very attire— the high neckline, the ruffled sleeves. The very format of the portrait reflects an economy where likenesses became increasingly accessible, yet were still coded by class and gender expectations. Consider also the labor that went into creating such a photograph versus its function for remembrance or social promotion. Editor: Definitely. She exists here as a cultural object. The slightly blurry edges, though— the way the photograph feels faded — to me, that softens the social commentary a bit. Curator: True, and these aging photographs offer something for contemporary engagement, too. As archives fade or disappear, our relationship to cultural inheritance undergoes continual shifts in understanding, where we rely increasingly on material remnants as guides. Editor: Thinking about it that way shifts everything. Maybe we aren’t just looking at a woman, but at the passage of time and how images subtly reconstruct themselves in our memories and interpretations. A materialist's lens and an artist's musings — perhaps that makes for the richest perspective of all.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.