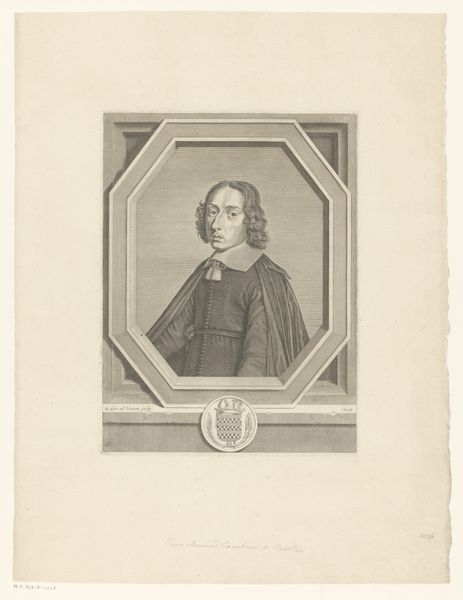

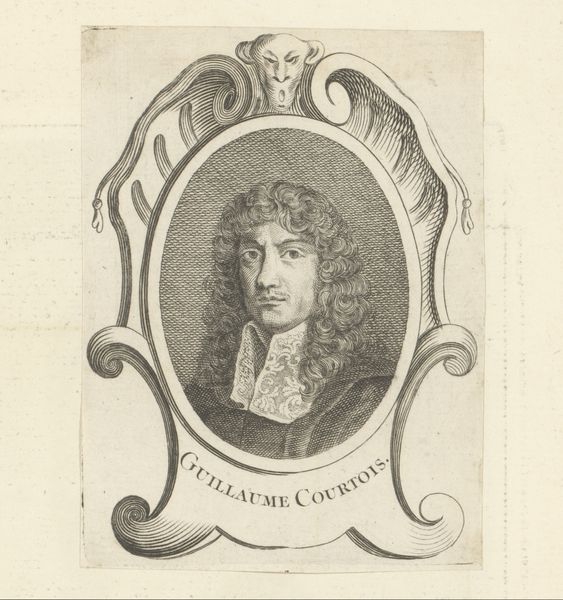

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 243 mm, width 186 mm, height 145 mm, width 102 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We're looking at "Portret van Baruch Spinoza," an engraving from sometime between 1730 and 1756, now at the Rijksmuseum. It's a portrait, obviously, set within an ornate frame. The figure himself seems… serious, contemplative even. What strikes you when you see this piece? Curator: What I find compelling is the image's place within the history of representing marginalized intellectuals. Spinoza, deemed a heretic in his time, is here framed, quite literally, by the very aesthetic traditions that would likely have excluded him. The baroque frame is an interesting counterpoint to Spinoza’s radical ideas. How do we reconcile the opulence of the presentation with the contentiousness of the subject? Editor: That's a great question. It's almost as if the frame is trying to legitimize him, bring him into the fold of established society, despite his, as you said, heretical ideas. Do you think that was intentional? Curator: Perhaps. Or perhaps it's an attempt to tame his radicalism, to domesticate a dangerous thinker by placing him within a familiar, acceptable visual language. The act of memorializing him through this portrait, however, still suggests a recognition of his lasting impact, doesn't it? How do you interpret the artist's intention in immortalizing Spinoza despite his controversial status? Editor: I hadn't considered that taming aspect, but it makes sense. Seeing it that way makes me consider how portraits are not always celebrating someone. They could be silencing them too, like putting a radical in a gilded cage. Thank you! Curator: Precisely. Art often functions as both celebration and control, a fascinating tension we can observe across history. Considering this paradox has been helpful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.