Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 118 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

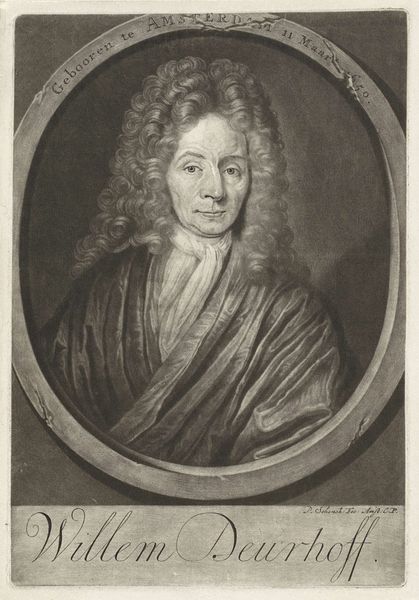

Curator: Welcome! Today, we’re looking at Jacob Houbraken's engraving, "Portret van Bruno van der Dussen," created sometime between 1749 and 1780. Editor: My first impression is one of elaborate presentation! The frame and the subject's attire convey considerable status and dignity. Is that intentional, do you think? Curator: Certainly. Portrait engravings like this were often commissioned to memorialize and disseminate images of prominent figures, solidifying their legacy and societal position. Notice how Van der Dussen is presented within an oval frame, almost like a cameo, emphasizing classical ideals. Editor: Yes, and the frame itself is interesting. It's so structured compared to the free-flowing curls of the wig. Is that contrast symbolic of anything specific to the Northern Renaissance, perhaps? Curator: In part, yes. The Baroque era loved precisely that interplay, that tension between structured, formal elements and more organic, dynamic forms. It's about showing both control and vitality. The wig, an undeniable symbol of power, literally overflows. Editor: Which, looking closer, almost feels a bit performative today. Back then, this visual language would have directly signaled authority. Is there any indication about the context of Van der Dussen himself? His life, maybe? Curator: He was likely a member of the Dutch elite, probably involved in commerce or politics, someone whose image warranted circulation. That elaborate wig was certainly not cheap! Editor: So, the portrait functioned almost as a form of early social media then, carefully crafted to convey power. The way identity is curated even through engravings. It feels quite resonant with today's culture, if you think about it. Curator: Absolutely. There is cultural memory imbued in portraits, revealing so much about a period's values and how people wished to be perceived, constructing layers of significance. Even in an engraving, we glean complex insights. Editor: Exactly, and grappling with these carefully constructed portrayals helps us critically examine how status and power continue to be visualized and reinforced, centuries on. Curator: A powerful way to conclude—connecting art history and our own experiences. Editor: Agreed, making connections bridges our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.