photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 81 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

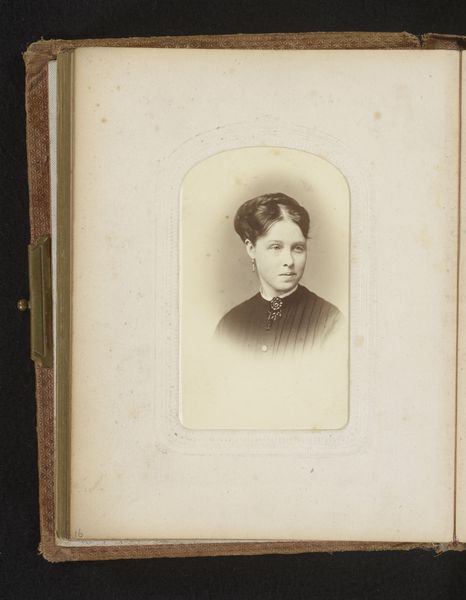

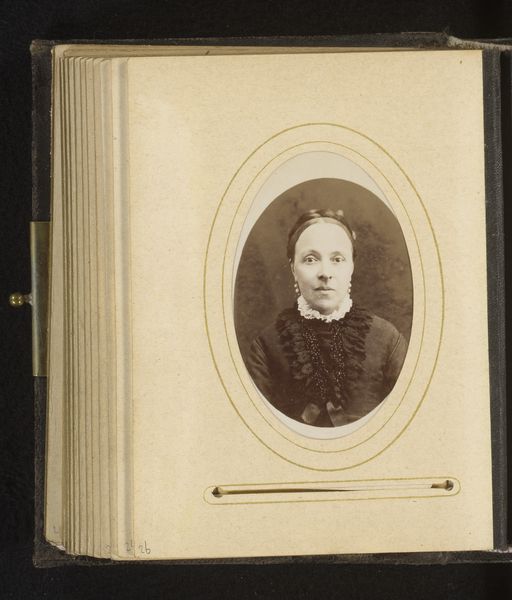

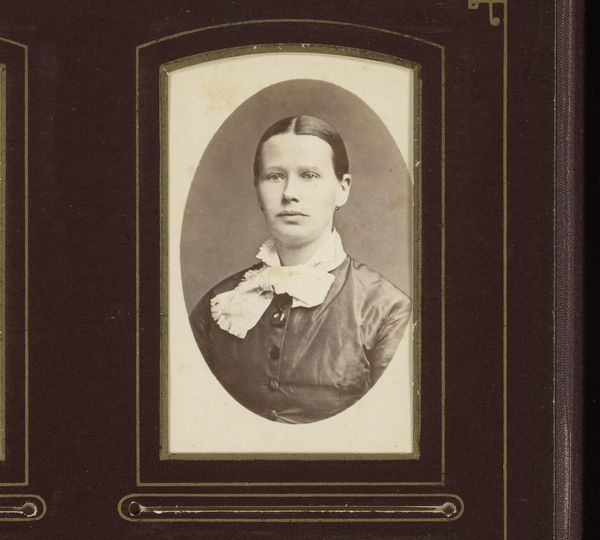

Curator: Here we have "Portret van een vrouw", a gelatin silver print created sometime between 1865 and 1887 by Jan George Mulder. It's presented in a bound album, characteristic of the era. Editor: Oh, she has a certain...dignity. A quiet strength in her gaze. I almost feel as if I shouldn't be looking, like I'm intruding on a private moment frozen in time. Curator: The process of creating gelatin silver prints was itself quite meticulous. It involved coating paper with a light-sensitive emulsion. This allowed for mass production of photographs and portraiture became much more accessible. Editor: Mass production, yet there's an intimacy here that defies that. It’s the curve of her cheek, the fall of light. It draws me to consider what the everyday involved for women in the mid 19th century, a sense of her personal style— even through what must have been a rather restricting set of social expectations, conveyed via a stern expression, carefully arranged hair, and buttoned-up coat. Curator: And note the careful presentation: an oval crop within the album page. These photograph albums functioned as material displays of social connection. It represented both family status and allowed individuals to engage with ideas of personhood and belonging. These objects were luxury goods, yet with the emergence of faster printing, were now far more readily available to the bourgeoisie. Editor: Interesting! But looking at the image, I cannot imagine that she would find the observation about faster printing so interesting. There must have been such pressure to remain dignified, so the ability to control image making via an affordable and simple photographic format had the dual function of permitting mass production, while providing intimate insights into the subject. Curator: I agree, though I suppose, that speaks to a larger question of access and image economy in the Victorian Era, a reflection that it still bears on our relationship to portraiture and its purpose today. Editor: Right, the medium impacts the message. But back to the woman—there is so much we don’t know, and it makes her presence here all the more remarkable. It's about trying to get as close as possible via imagination. Curator: A testament, perhaps, to photography’s lasting power to invite consideration. Editor: It’s a little haunting, really.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.