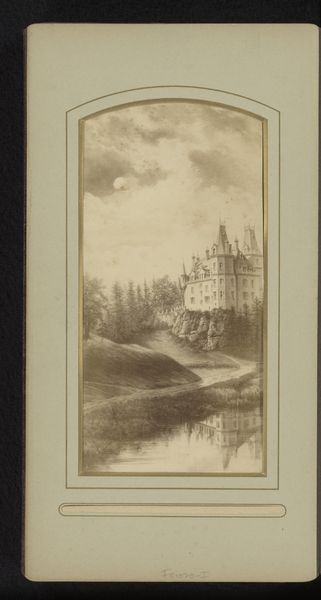

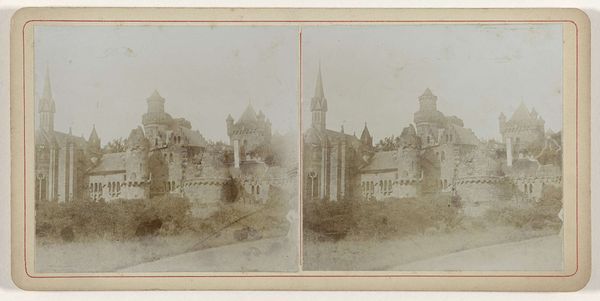

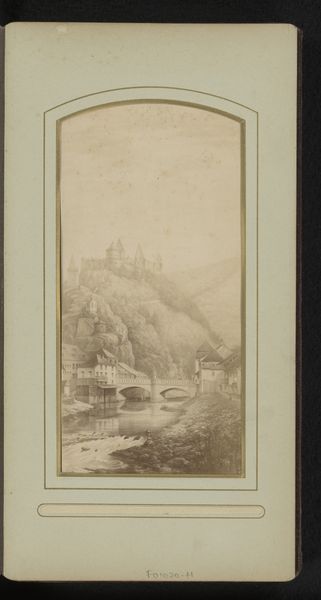

Gezicht op het Kasteel van Pierrefonds, Frankrijk, met op de voorgrond een meer 1860 - 1870

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is an early photographic image titled "View of the Château de Pierrefonds, France, with a Lake in the Foreground," captured sometime between 1860 and 1870 by Ferrier Père-Fils et Soulier. Editor: It's incredibly still. That mirrored reflection... the scene feels staged almost, in its composure and rigid horizontals. The tonal range is pretty tight, though. Limited, compared to today. Curator: Think about the symbolic weight of a castle at that time—what it evoked about power, history, lineage, but also perhaps about decay and transformation. Castles had become ripe territory for romantic artists precisely because of the narratives embedded in their stones. Editor: And look at how this particular image participates in those narratives. Notice the materials: this is likely an albumen print. That glossy sheen wasn’t just aesthetic. It spoke to technological advancements, the labor-intensive process behind its making, the chemistry involved. There’s a new kind of ownership being staked out here, documenting these sites for wider consumption. Curator: Precisely! And that stillness you mentioned, I suspect that also feeds into a collective fascination—a cultural obsession even—with places like Pierrefonds. A still image captures the fleeting moment and arrests time, offering an eternal reflection, so to speak, of both its architectural might, and perhaps the wistful sense of loss around its historical place. Editor: Right. You think of all the workers involved extracting the raw materials to build the castle originally, and all the labour involved in sustaining it. This photograph aestheticizes and condenses all of that messy, sprawling context, while at the same time participates in its cultural reproduction for new consumers. Curator: What do you make of the romantic aesthetic combined with industrial photography in this instance? Does that change its effect, compared to, say, a painted rendering of Pierrefonds from the same period? Editor: Good question. This image is materially indexed to a particular time. Whereas painting could always evoke other modes of idealization, photography feels like an immutable capture of a place at that particular point in time, for both good and ill. So I guess the romanticism has more of a historical bent here. Curator: Absolutely, a photograph implicates time, labor and social changes even if its aesthetic draws from romance. Thank you for sharing your reflections! Editor: Likewise. It’s revealing how an image like this opens up so many points of consideration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.