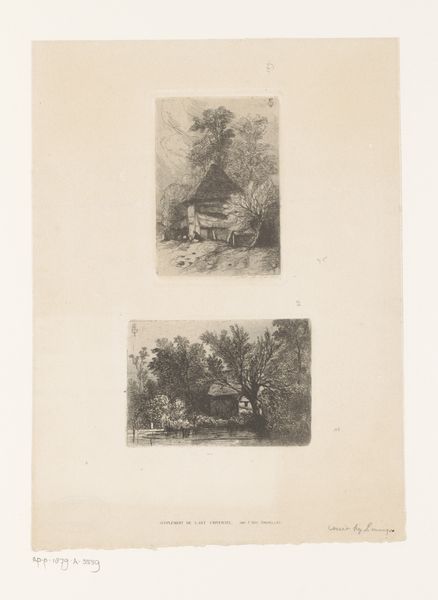

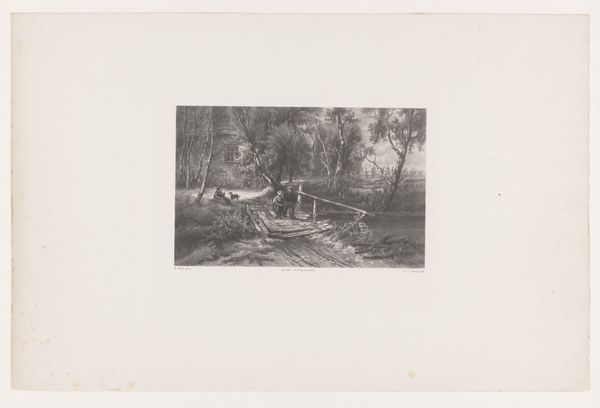

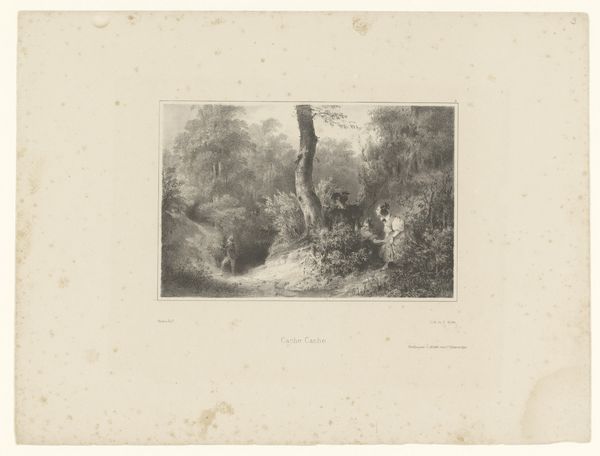

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 207 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I find this work so charming. It is titled *Landschap met een watermolen en een visser*, which translates to Landscape with a Watermill and a Fisherman, made by Andreas Achenbach in 1862. The etching on paper possesses such detail; I can almost smell the damp earth and hear the water. Editor: It definitely has an ethereal quality. The monochromatic palette and the way Achenbach renders the light gives the scene an almost dreamlike aura. You know, these picturesque scenes also often acted as visual assertions of property and privilege. How does this imagery play into the land ownership politics of the 19th century? Curator: Oh, absolutely. These idyllic depictions often romanticized rural life, conveniently glossing over the hardships faced by working-class individuals and families. The watermill, while appearing quaint, powered industry, and the landscape held very different meanings for those who toiled on it versus those who merely observed its beauty. It’s always about perspective, isn’t it? The lone fisherman also contributes to this Romantic narrative. He represents someone interacting peacefully with the landscape but is not integral to any process within it. Editor: Exactly! And you touched on something really crucial here. I see the etching itself almost performing a kind of historical layering. Consider the tradition of etching, typically favored by men, like Andreas, for art with this subtle but distinct political charge. It suggests perhaps this medium itself can offer us some clues regarding its relationship to property, the history of landscape representation and environmental exploitation. Curator: That's fascinating. Thinking about the way Achenbach carefully constructs this vision of harmonious existence. Do you get the sense that, while picturesque, something feels missing from this world? Or that something might soon be coming to an end? Editor: Well, let’s be honest, such selective serenity always demands critical analysis of which stories are omitted and who benefits from such idyllic images. This can open up much deeper dialogue about whose visions and perspectives were included and amplified. Curator: Such landscapes become so much more meaningful—they teach us how to question those kinds of landscapes and imagine the world they might not want us to imagine. Editor: Precisely. Landscapes aren't merely pretty pictures, they are laden with narratives of class, labor, and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.