print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 144 mm, width 91 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

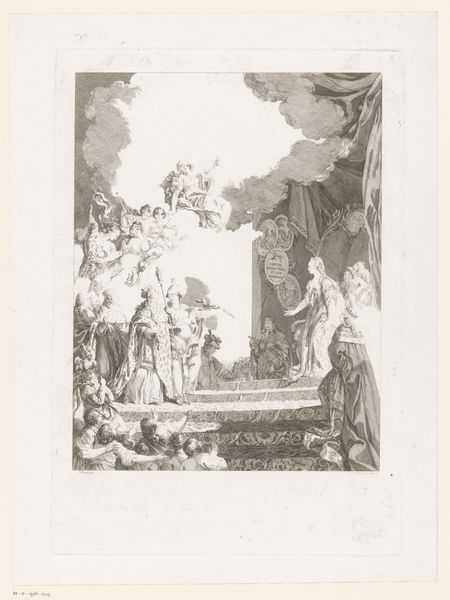

Curator: Looking at this engraving by Simon Fokke from 1758, titled "Piety Showing the Bible to Two Women," my first thought is the sheer delicacy of the lines, an impressive feat of engraving. Editor: Indeed. And it feels almost ethereal, doesn't it? The composition is intriguing, there's a strong Baroque sensibility here with the theatrical presentation of piety and her biblical teachings. But what does this performance achieve socially? Curator: Well, consider the social dynamics of 18th-century Dutch society. This print, circulated widely, reinforced the role of religion—particularly the accessibility of scripture—in shaping moral behavior and domestic life. The scene suggests that religious knowledge is actively bestowed upon women, implying their vital role in upholding piety within the household. Editor: I see that. But I'm more interested in the labor that created this image. Engraving involved meticulous craft, the engraver carefully translating image to a reproducible form. It speaks volumes about the production and dissemination of such ideologies. The print wasn't just accessible; it was actively propagated, materially imprinted onto culture via reproducible means. Curator: Absolutely, we shouldn't ignore the socio-economic dimension. Prints were relatively affordable, broadening access to visual culture. That accessibility shapes how people internalize certain messages or construct their worldview. Religious and political messages get infused in quotidian objects of domesticity and get circulated through printmaking. Editor: And think about the paper itself, the ink—raw materials transformed into conveyors of ideology. These materials have history and geography all their own. This print shows the piety but also points to an industrious printing infrastructure. How many copies were made? Where were they sold? To what classes of society? The answers expose social history, but also a commercial structure deeply entrenched in its time. Curator: These are excellent points. By analyzing who commissioned and bought the print we reveal much about Dutch piety but also about art patronage in the era. So who controlled production in this manner, and who was exposed to such work, dictates meaning and therefore societal values. Editor: Agreed. These delicate lines aren't just aesthetically pleasing, but represent physical manifestations of broader power dynamics at work, disseminating ideologies to a wide consumer base. I am moved when seeing the way something handmade becomes a machine to distribute en-mass. Curator: Seeing these kinds of works always helps to reflect on the visual codes in the present day. Thank you, it makes me want to review what I thought about the church back then! Editor: It helps us think how meaning comes materially to take hold and how meaning can shift once material contexts are altered too. Fascinating, really.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.