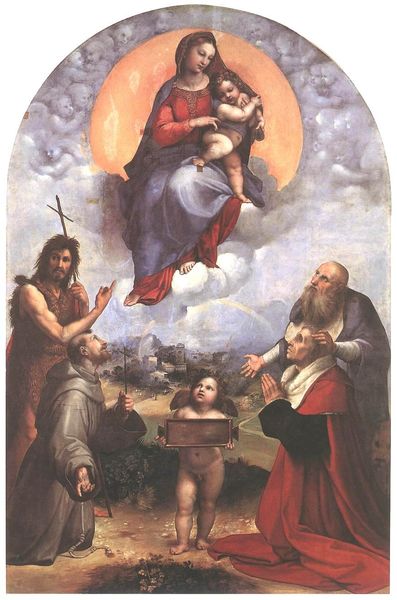

Christ in Glory with St. Benedict (c.480-547), St. Romuald (c.952-1027), St. Attinia, St. Grecinia and the donor, abbot Buonvicini 1492

0:00

0:00

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

high-renaissance

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

jesus-christ

#

christianity

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

#

portrait art

Dimensions: 308 x 199 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Let's consider this oil on panel, a 1492 altarpiece by Domenico Ghirlandaio titled "Christ in Glory with St. Benedict, St. Romuald, St. Attinia, St. Grecinia and the donor, Abbot Buonvicini". Editor: My immediate reaction is that the colors are surprisingly vibrant for its age. And there's a distinct layering, a kind of visual hierarchy, isn’t there? Curator: Absolutely. Ghirlandaio strategically places the figures within a clear hierarchy, reflective of Renaissance social order and devotional practice. Christ enthroned at the top in the mandorla of clouds, then the Saints, and finally the kneeling figures, including Abbot Buonvicini, the patron who commissioned this piece for his abbey. Editor: Yes, that hierarchy! It strikes me as quite pointed. I mean, those kneeling figures, particularly the women saints, seem almost minimized, both literally and figuratively, in terms of their agency within the narrative. Their placement really speaks volumes about their roles, doesn't it? Curator: It does highlight the prevailing social structures. The painting reflects the Church's and societal expectations regarding gender roles at the time. It is worth noting how male monasticism, specifically the Benedictine order with St. Benedict, held immense social power. Ghirlandaio reinforces this by his depiction of St. Romuald and the donor abbot, each figure a testament to institutional authority. Editor: And the details—notice Christ holding the book inscribed with "A" and "Ω," Alpha and Omega—reminds us of His all-encompassing presence. But that very same image of dominance can be exclusionary. Who felt represented then, and who feels represented now? Curator: These are essential questions to ask. The very act of commissioning such a painting solidified the donor's status. Art served as a powerful tool for social affirmation. However, the painting simultaneously served a broader devotional purpose, accessible to all who entered the church. Editor: Understanding how such artwork was utilized in society provides us crucial insight into understanding its context and how these narratives perpetuate ideas about gender, social class, and power to influence not just devotion but action in the world. It allows us to draw links with other narratives in media throughout time. Curator: Reflecting on its place within art history, it demonstrates a distinct move towards humanism; yet it cannot be extracted from the power relations embedded within its historical context. Editor: Precisely, we can see that the painting still stirs up conversations around gender, agency, and how devotional spaces reflect and construct realities even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.