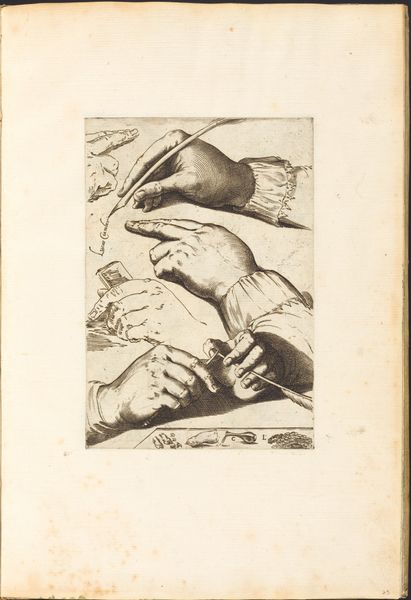

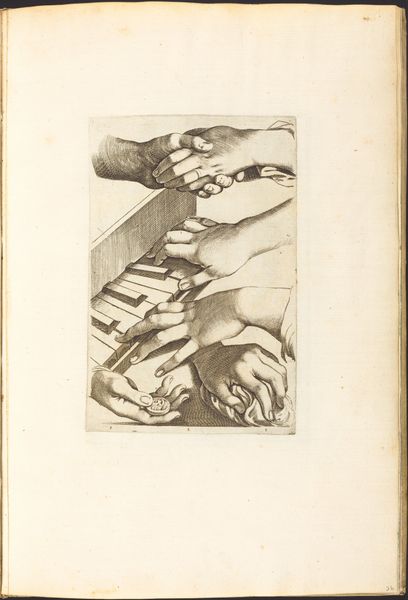

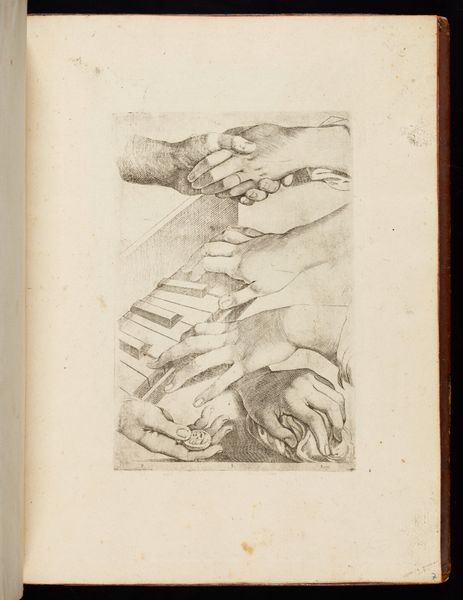

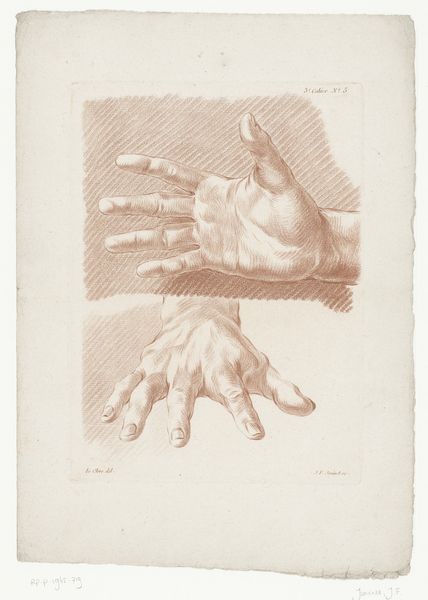

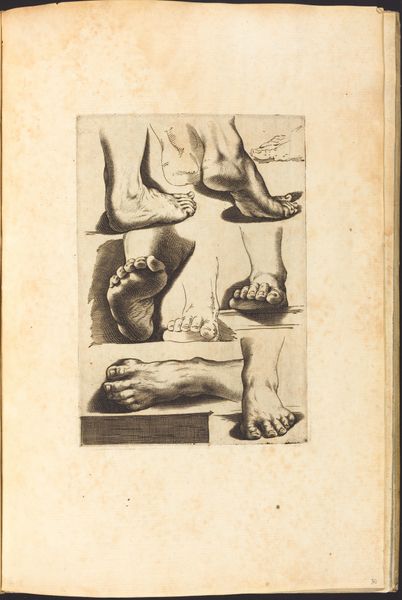

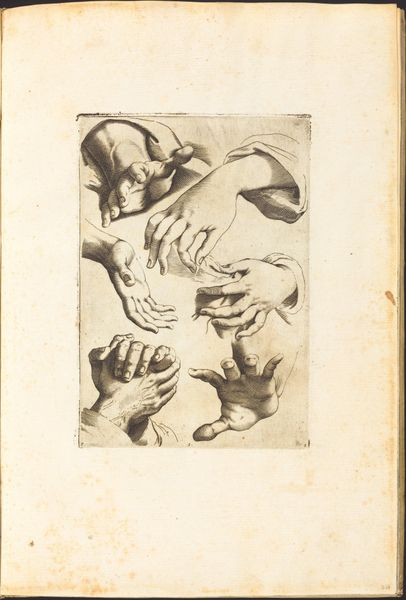

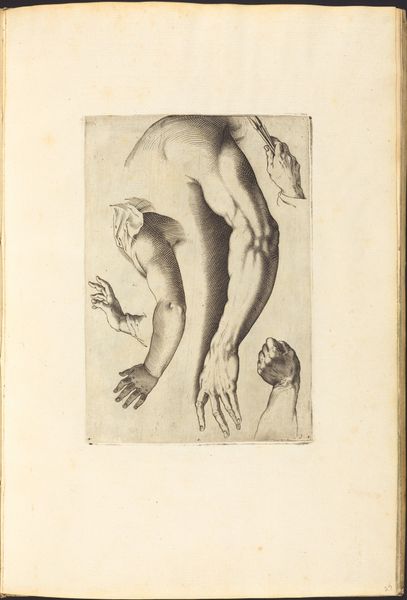

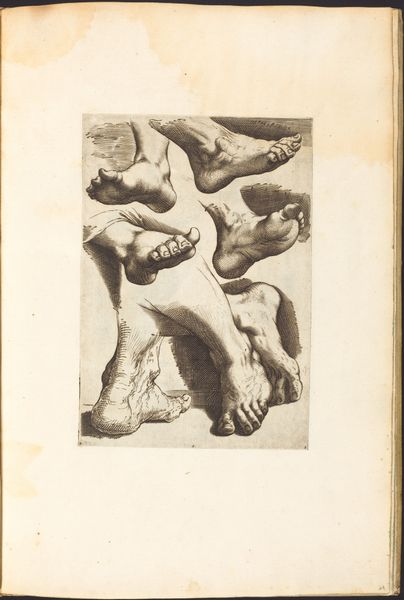

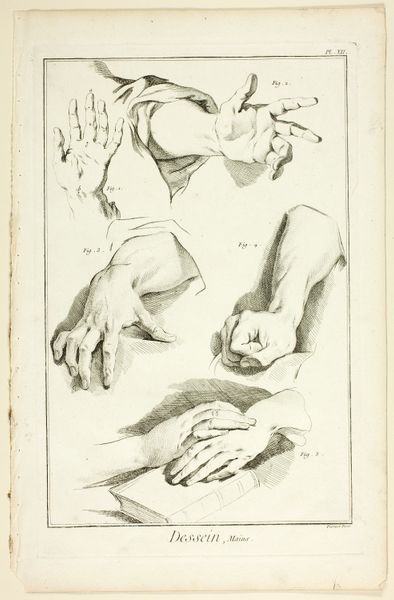

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

engraving

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: This is “Print from Drawing Book,” an engraving in ink on paper by Luca Ciamberlano, dating from around 1610 to 1620. The subject matter is unusual: disembodied hands engaged in various crafts. How would you interpret this work? Curator: It's fascinating to see hands elevated as the primary subject. They become symbolic actors. What do these actions—sharpening a quill, drawing a line— evoke for you? Is it about skill, artistry, perhaps even the passing of knowledge? The baroque embraced such dramatic, intimate details. Editor: I see a strong emphasis on the practical. But they feel isolated, almost clinical. I suppose it is a study aid to help with realism? Curator: Precisely. The baroque interest in realism demanded such precise observation. But the hand, culturally, is a potent symbol. It’s agency, creation, benediction, or even punishment. What symbolic charge do you find in depicting *only* hands, detached from the figure? Editor: Well, the removal of the figure focuses all the attention on the craftsmanship and skill. But removing the body can make these familiar actions seem otherworldly, uncanny, and haunting even. Curator: An interesting point. We tend to see hands as extensions of a self. Deprived of that connection, they become like tools, yes, but tools imbued with memory. Each gesture carries a history of learning and practice. Doesn’t the selection of the hand itself reveal more broadly the psychological dimensions of making? Editor: I hadn't considered that, the psychological dimension. Thinking about hands, in the context of skill, reminds me that craftsmanship involves not only technical skill but dedication, training and memory. Curator: Indeed, we begin to appreciate how cultural memory and human artistry coalesce.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.