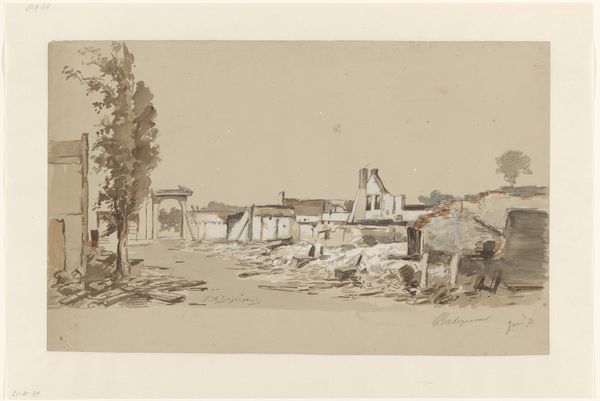

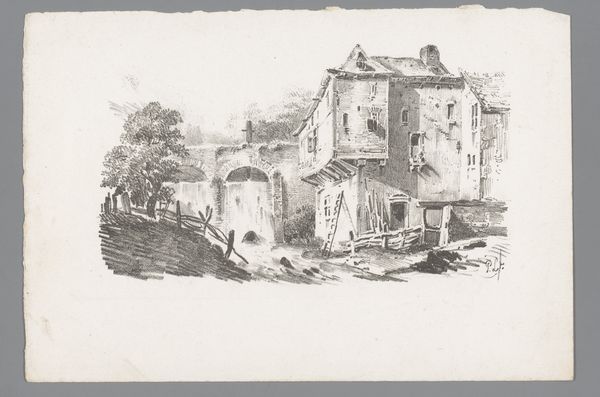

drawing, painting, paper, watercolor, architecture

#

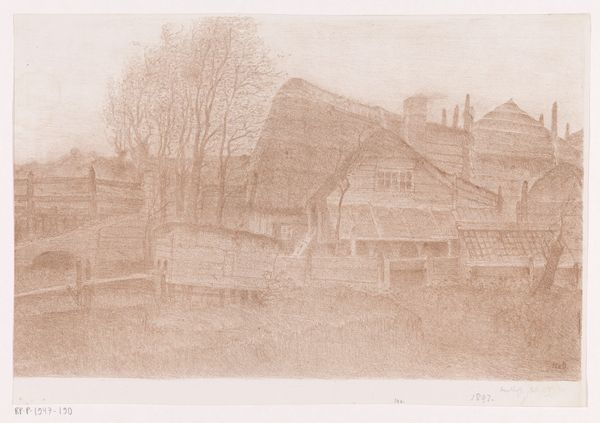

drawing

#

water colours

#

painting

#

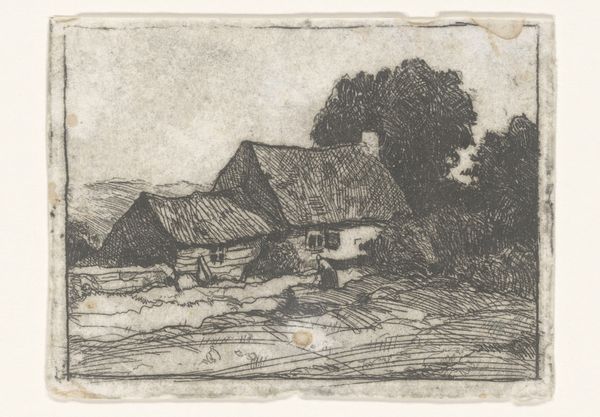

landscape

#

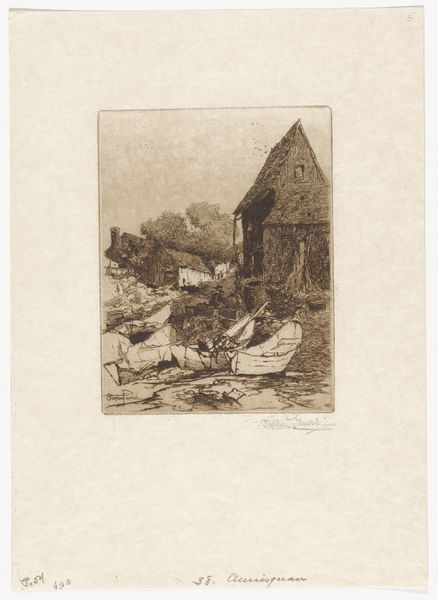

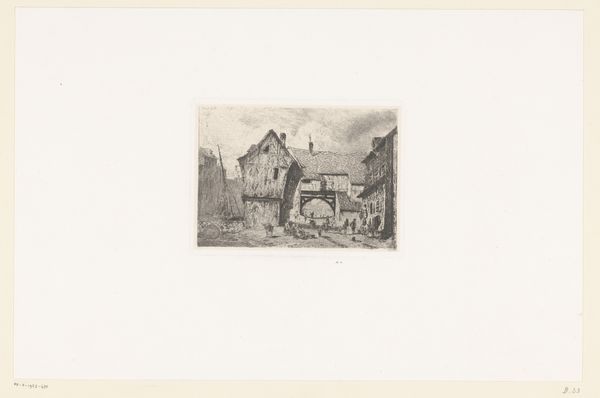

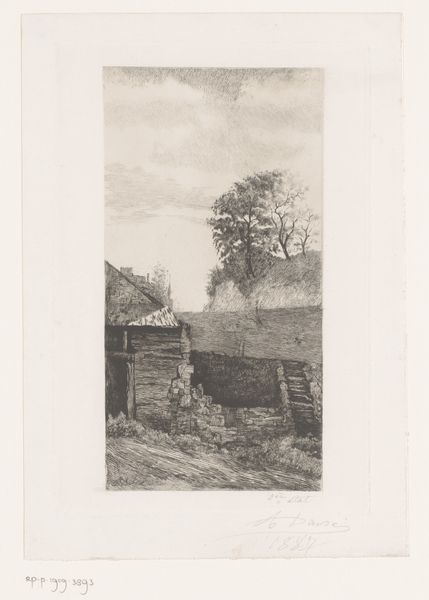

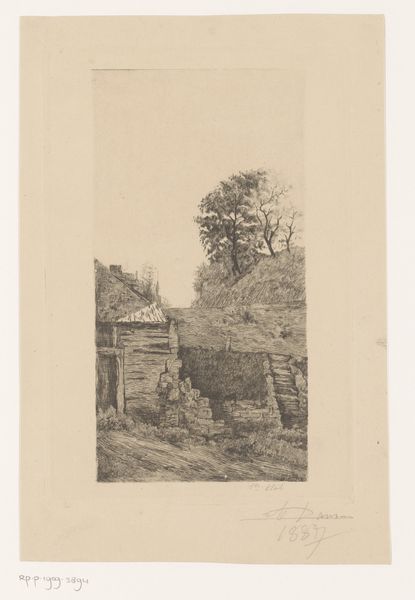

etching

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

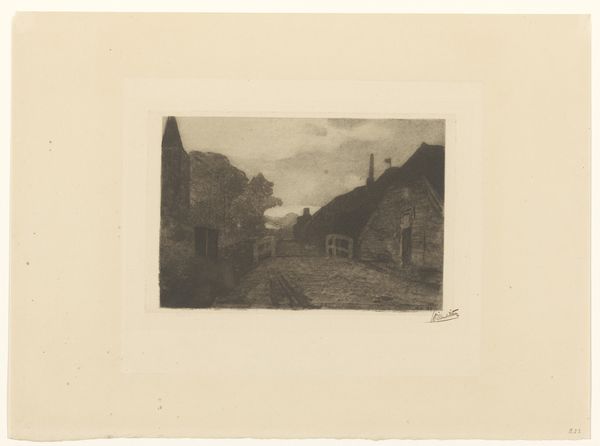

Curator: This watercolor, “Segovia,” was completed in 1850 by Karl Peter Burnitz. Currently it is held at the Städel Museum. What's grabbing you about it? Editor: I’m struck by the tonal range. It feels monochromatic at first, yet the delicate watercolor application lends this ghostly ethereal quality. And the buildings almost feel as though they are emerging from the landscape itself, as the natural landscape appears integrated and to even merge with architecture of this city view. Curator: It’s an intriguing interpretation of architectural landscape, to be sure, but the style aligns very distinctly with Romanticism and with the associated fascination with the picturesque and sublime qualities of the natural world. Note the attention dedicated to capturing the textures of rock formations against these quaint European buildings. Editor: But whose vision of Segovia is this? A romanticized version, surely. Where is the social reality of the city? The grit? By rendering Segovia in almost solely sepia tones, is Burnitz not contributing to an exclusionary view that focuses only on an idealized past? Curator: You raise an important point about representation, particularly within the historical context. Burnitz was very interested in historical architectural styles and his artistic cohort circulated ideas about landscape's role in conveying national identity, so the intent probably involved celebrating Segovia's enduring architectural presence. The absence of contemporary inhabitants may even play into that idealized vision of an eternal past. Editor: Still, I can’t help but wonder if the artist actively obscures the diverse populace of the city, focusing instead on these large boulder shapes that mimic monumental architecture, symbolizing a kind of imposing history, perhaps a way to show dominance and national prowess. What do you suppose this work meant for its viewers? Curator: In its time, a watercolor like this could circulate among educated bourgeois, and would evoke sentimental, possibly even patriotic feelings by representing European landmarks and the historic grandeur found there. Editor: It's interesting how tastes shift. Today, with greater awareness of whose histories get told and whose are omitted, a piece like this invites, I think, more critical viewing. I mean it encourages me to think deeply about whose stories are considered "monumental" and "worth" painting. Curator: Indeed. That reflection can really enhance our appreciation for art history and even the silences that are expressed alongside historical subjects, don't you think? Editor: Absolutely, to have that tension is exactly why these historical artworks remain relevant and really become critical documents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.