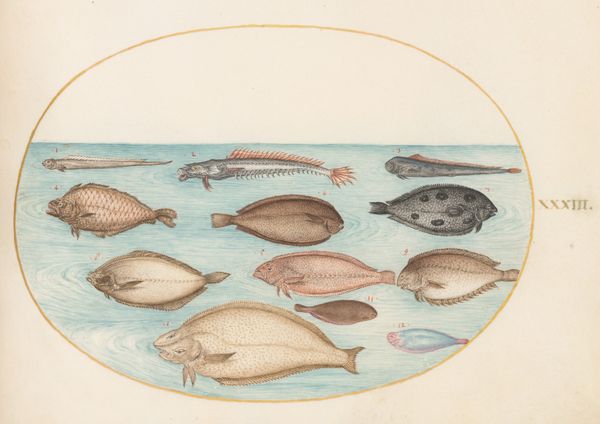

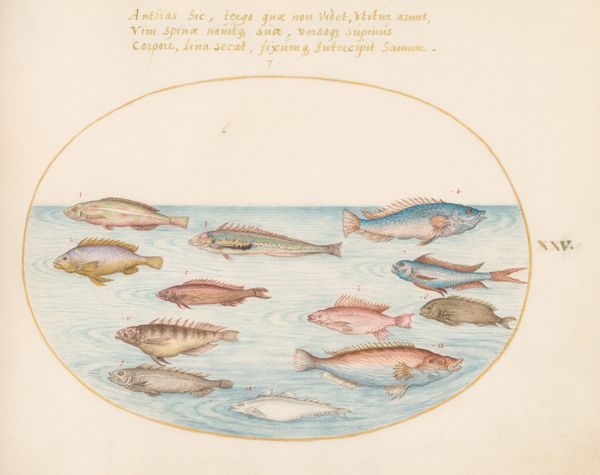

Plate 18: Boarfish, Razorfish, Butterfish, a John Dory, and Other Fish c. 1575 - 1580

0:00

0:00

drawing, coloured-pencil, watercolor

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

Dimensions: page size (approximate): 14.3 x 18.4 cm (5 5/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This intriguing image before us, titled "Plate 18: Boarfish, Razorfish, Butterfish, a John Dory, and Other Fish," comes to us from the late 16th century—created between 1575 and 1580, to be precise. Joris Hoefnagel rendered this colorful scene with watercolor and coloured pencil, seemingly capturing a vibrant underwater tableau. What's your first impression? Editor: My initial reaction is that there’s a kind of disquieting stillness despite the color, the array of species. These fish are presented as specimens—arranged almost scientifically within that defined, golden oval, as though frozen for examination. It brings to mind the long history of humans classifying, cataloging, and exerting power over the natural world. Curator: Precisely! That scientific impulse was really ascendant at the time. What we’re looking at is a quintessential example of early scientific illustration. These meticulous details serve as more than just aesthetic elements; they are a form of visual record, a catalog of the natural world as it was then understood. In terms of symbolism, this almost feels like a transition between medieval bestiaries and a modern zoological study. Editor: Absolutely, and I'd argue that cataloging natural specimens and their assumed knowledge were tightly tied to economic exploitation and colonial domination. You see the beginnings of that tension in an image like this. These aren’t just colorful creatures; they're resources, items of curiosity and commerce. The artistic choice to isolate these specific fish within an oval frame and arrange them symmetrically makes them appear like trophies in a collector’s display. How does that strike you? Curator: I see your point. There’s definitely a power dynamic present. The act of naming and classifying—a drive for knowledge, but as you suggested also a type of conquest. The precision of his rendering elevates them, but also sets them apart. Looking closely, you'll notice the individual textures, the subtle gradations of colour—even the glint in their painted eyes. This evokes a certain awe, but it also suggests a degree of control over nature. Editor: Right. The "gaze" reflected in each fish evokes their subjugation. So while the artwork succeeds as an almost clinically accurate document of each aquatic species and the potential beauty of that, the painting functions, in my view, as more of a historical reflection on human-centric worldviews, which continues to the present day. Curator: It's fascinating to consider how this piece straddles that line, a mirror reflecting not just the underwater world, but also humanity's complex relationship with it. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.