drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

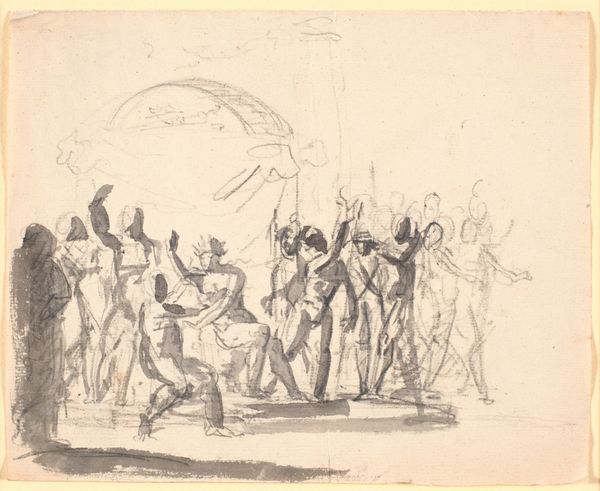

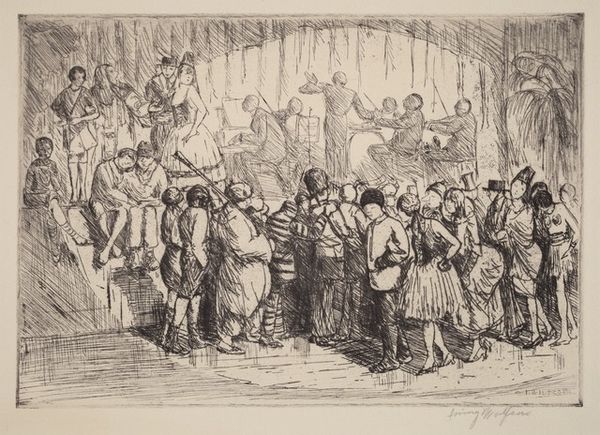

Curator: Here we have a pencil drawing attributed to Paul Delaroche, titled "Le retour de la prise de la Bastille," or "The Return from the Storming of the Bastille." Editor: Wow, my first thought is just how kinetic it feels. Despite being a pencil sketch, there's so much energy conveyed in the crowd scene, like a snapshot of raw celebratory chaos. Curator: Indeed. Delaroche, a well-regarded academic painter, often depicted historical subjects. This drawing, I suspect, offers his vision, possibly a study, of the fervor that surrounded this key moment in the French Revolution. What this image really communicates is the *idea* of revolution. Editor: I'm particularly struck by the labor involved, even in this sketch. The repetitive marks creating textures, the careful rendering of each figure contributes to the understanding that this was not some quick uprising, but a movement painstakingly made by the masses. Notice that some white paint was added, and the effect of that limited, calculated touch to bring it forward as an exciting, energized affect. Curator: Absolutely, but it also seems important to consider the visual tropes being deployed here. The raised figure on the shoulders of others, a wreath around his head, evokes a distinctly Roman triumphant return, does it not? Delaroche seems interested in framing the event as having historical importance, embedding the imagery into our accepted history. Editor: I agree. And in looking more closely, it also draws attention to the materials. The clothing isn't the finely woven materials, and there aren’t perfect pleats; they were items worn for necessity as labor demands. Look also how their clothing reveals both labor and the influence of revolutionary disruption to labor: their pant legs cut short! This makes Delaroche's commitment to the real of what is taking place to give way into a more personal style. Curator: The interesting element of that commitment can also mean, that Delaroche, depicting it as such an immediately identifiable and heroic moment is subtly, and perhaps subconsciously, lending it a weight of inevitability. And I find that telling given the artist’s positioning in the established artistic and political milieu of his time. Editor: An interesting thought. It speaks to art's dual role: depicting, while simultaneously influencing, the narratives we tell ourselves about history. What this rendering does—and how the art's patronage may have demanded it—opens up new avenues into historical research methods on art and aesthetics themselves.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.