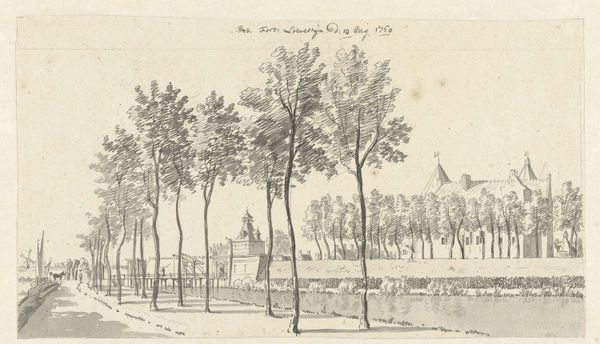

Dimensions: height 154 mm, width 230 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Gezicht buiten Haarlem," or "View outside Haarlem," a print made with etching and engraving by Johannes Swertner in 1763. What strikes you first about this cityscape, Editor? Editor: There’s a certain placidity to it, almost melancholic. The subdued tonality, the solitary figures, the trees bordering the lane... it suggests a space for contemplation, removed from the city's hustle. It feels like the edge of something. Curator: That sense of being on the periphery is key, I think. The artwork, in its seemingly straightforward depiction, subtly speaks to the power dynamics inherent in viewing and representing space in the Dutch Golden Age. Who gets to be *in* the picture, and how are they positioned relative to the landscape and the city itself? Look closely at the carriage; who travels within and where are they going? Editor: The path cuts like a tunnel through the arboreal boundary, yet delivers to the periphery of Haarlem in the distance. One might expect the light-filled vista in the foreground to highlight nature’s bounty but here we instead find horses at feed in front of another barrier. What visual memory would have triggered for a Haarlem resident gazing at this image in 1763? Curator: That’s precisely the question, isn't it? Consider the symbolism of Haarlem itself during that era. It was a city experiencing a slow economic decline, no longer at its peak, yet retaining a powerful civic identity. This print, then, captures not just a physical space, but a specific moment of transition, a feeling of a community reflected against the backdrop of a changing social structure. And those symbols -- trees, architecture, farm, traveler -- carry so much more narrative baggage in light of that era’s realities. The carriage almost takes on a funereal feeling, doesn’t it? Editor: Yes, exactly! The visual language evokes not only place, but temporality: perhaps it echoes of decline even as the technique recalls more glory in detailed replication of familiar architectural reference points. Curator: Looking at this piece offers a stark, albeit beautiful, reminder that what appears at first glance to be an innocent landscape is, in fact, a densely layered commentary on identity, progress, and societal power at a specific crossroads in time. Editor: Absolutely. It shows how landscapes, seemingly innocuous, become potent vessels of collective memory and emotional significance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.