drawing

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

imaginative character sketch

#

16_19th-century

#

quirky sketch

#

cartoon sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

academic-art

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

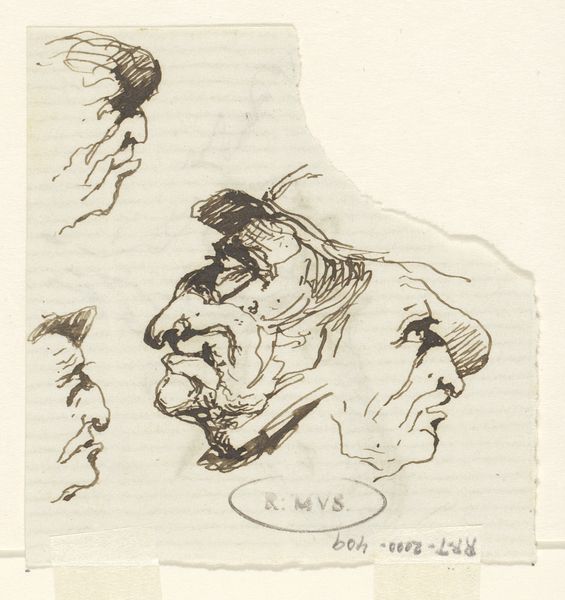

Dimensions: height 79 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

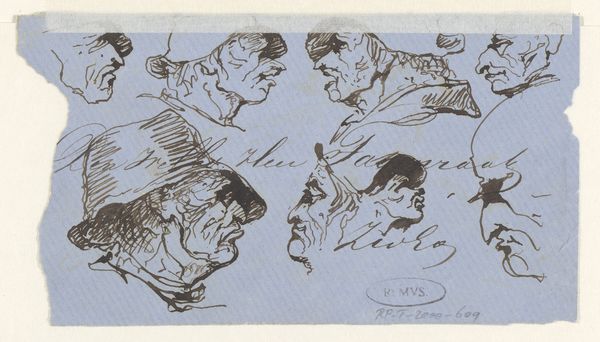

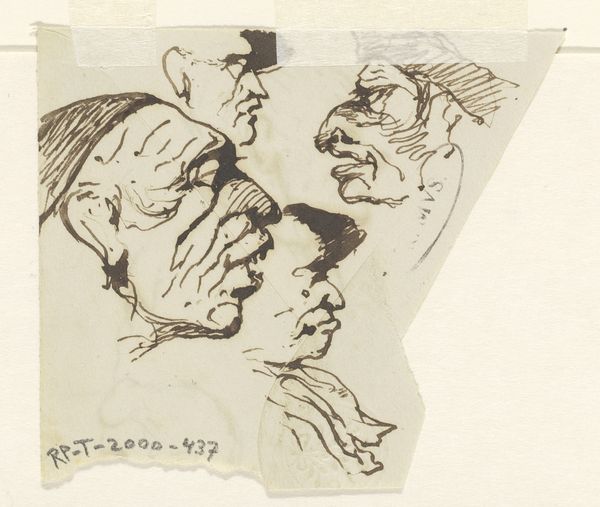

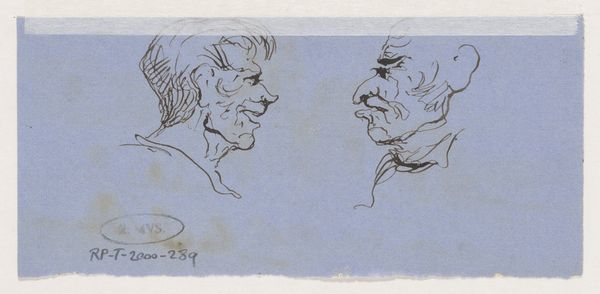

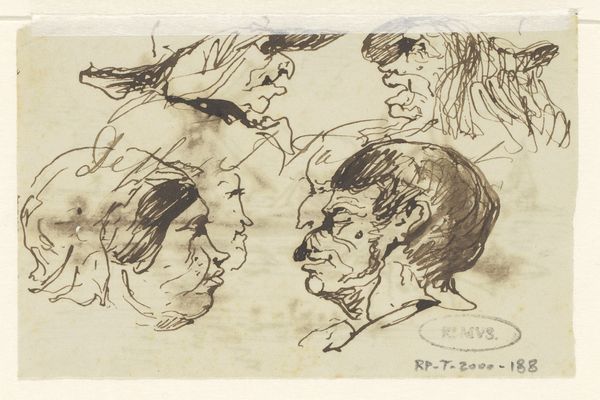

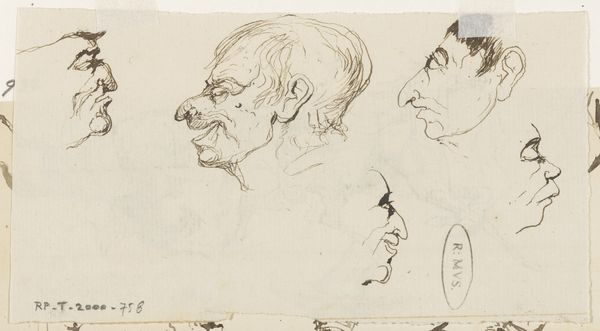

Curator: This drawing, titled "Drie Koppen," meaning "Three Heads," is attributed to Johannes Tavenraat and dates back to somewhere between 1840 and 1880. The Rijksmuseum holds this interesting drawing as a valuable piece of their collection. Editor: Interesting, they’re rapidly sketched in what seems to be ink. They all have these very pronounced noses, don't they? Quite caricatural. Curator: Yes, the rapid ink strokes capture these subjects with, what I interpret to be an aim towards... well, maybe some satirical intent is present. The style also connects to artistic currents that embraced Realism but had not quite reached that complete academic goal. I think he had a knack for capturing humanity's often humorous nature. Editor: It’s the simplification that I find so engaging. Tavenraat doesn't waste a single line; each mark defines form, texture, and even, to some extent, the character of the sitters. Notice the density of lines to create shadowed effect. The artist is clearly concerned with conveying depth in this artwork. Curator: Absolutely. Consider, however, the context of the 19th-century Netherlands. This was a time when national identity and bourgeois values were on the rise. A piece like this, whether intentionally or not, enters into that discussion about how social roles, even individual physiognomy was viewed and categorized. This simple drawing raises questions about class, representation, and even, the artist’s position. Editor: But doesn’t its artistic merit come from the economy of line and the spatial relationships between these heads on the page? These aren’t formal portraits destined for public display. They strike me as studies, sketches, perhaps even doodles meant for the artist’s private contemplation, as though we’re seeing into his thought process. Curator: And yet, by preserving it, and displaying this drawing, we, as custodians of cultural heritage, place these intimate musings within a public domain, thereby asking it to speak beyond the merely formal and begin an address that involves public and cultural life. Editor: A fair point. Though, I must confess, it’s the raw immediacy of Tavenraat's line that resonates with me most profoundly, almost akin to catching a fleeting expression in a mirror.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.