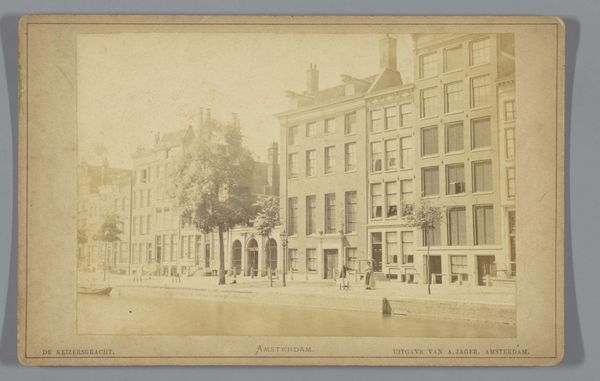

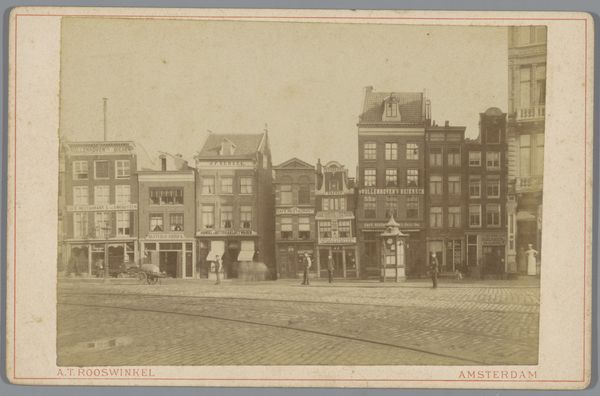

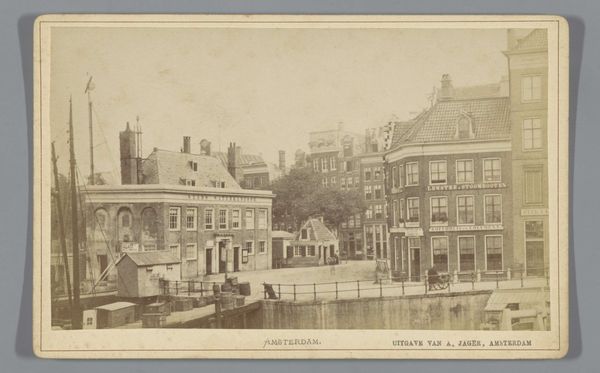

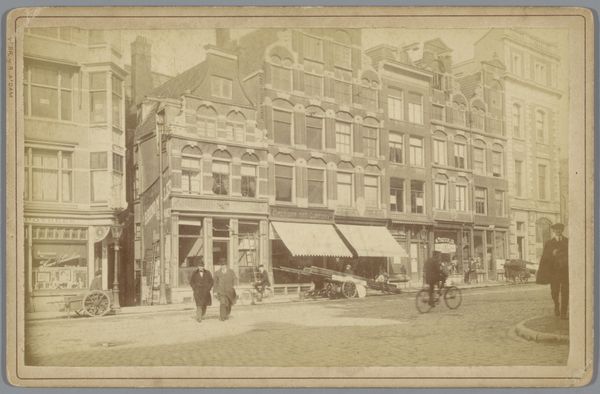

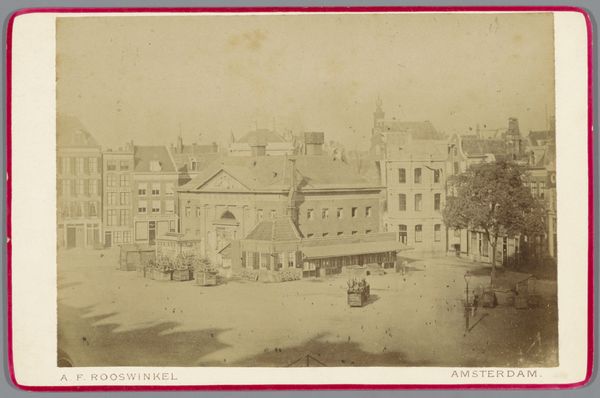

Botermarkt en standbeeld van Rembrandt voor de ingang van de Reguliersdwarsstraat, gezien vanaf het Thorbeckeplein 1865 - 1875

0:00

0:00

andriesjager

Rijksmuseum

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 108 mm, width 166 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Andries Jager’s gelatin silver print, taken between 1865 and 1875, captures the Botermarkt in Amsterdam, showcasing Rembrandt’s statue at the entrance of the Reguliersdwarsstraat. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What do you think? Editor: My initial impression is stillness; it is such a hushed city scene, devoid of any lively elements. A frozen moment with a sense of formality. Curator: The calmness mirrors photography's social role at that time: primarily used for documentation, reinforcing power structures and solidifying national identity. This ordered composition serves not just to capture a market square, but to establish Amsterdam’s identity during a time of great social change. The image projects a sense of civic pride and accomplishment by immortalizing its landmarks. Editor: Absolutely. One must view photography beyond the lens of simple reproduction; the frame dictates what stories can, and cannot, be told. Do you think this memorializing act plays a part in crafting a kind of visual power dynamic within urban life? Curator: Absolutely. Public statues invariably influence socio-political interactions. Erecting Rembrandt’s likeness becomes part of that narrative, reminding the population about artistic history, but potentially obscuring underrepresented perspectives of everyday folk at the Botermarkt. Editor: So even in something that seems ostensibly objective like this gelatin silver print, there are power dynamics at play. This forces us to interrogate photography not just as historical evidence, but also as an agent of culture production with selective visibility. Curator: Precisely. Considering Jager’s print critically means understanding how its very creation intersects gender, race, and political forces present in late 19th-century Dutch culture, reminding us about whose stories often go unrecorded or undocumented. Editor: It’s so easy to passively view old photographs as simply documentation, however, by teasing out these intersecting cultural concerns, one can use artworks to encourage dialogue about race, gender, identity and class. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.