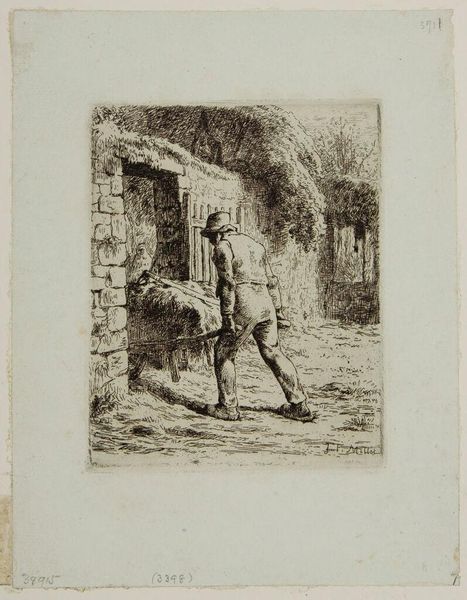

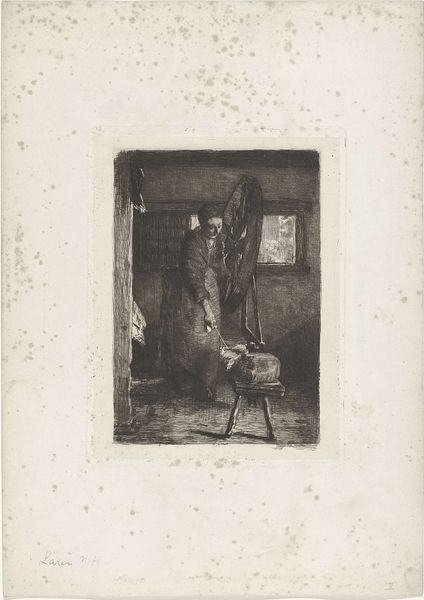

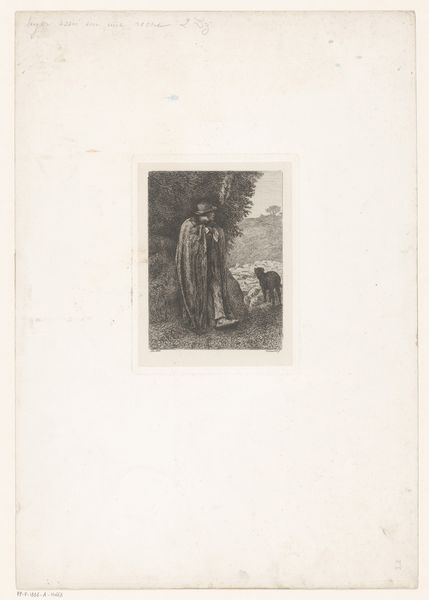

drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

french

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

ink

#

france

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: 168 × 135 mm (image); 279 × 227 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. We are looking at Jean-François Millet’s “Peasant with a Wheelbarrow,” created around 1855. It’s an etching, printed in ink on paper, and part of the collection here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: My first impression is of weariness. The lines are rough, mirroring the peasant's likely hardscrabble life. The palette is subdued, almost monochromatic. It feels very…stark. Curator: Stark, yes, and deliberately so. Millet was part of the Realist movement, focusing on depicting the lives of working-class people, particularly rural laborers, without idealization. He sought to capture the dignity—and often the hardship—of their existence. Consider the political implications of such portrayals in 19th-century France, a period marked by stark class divisions. Editor: It feels radical. Instead of glorifying war or royalty, Millet directs our gaze to the backbone of society, those who sustain everyone else. There's a social commentary embedded within this seemingly simple genre scene. The turned back of the figure is powerful: the message seems to be, "See this anonymous labor. Understand what supports your society". Curator: Precisely. Millet presented the peasant’s labor as an integral and valid part of French life, often challenging the romanticized or pastoral views that were fashionable at the time. And remember, these images circulated as prints. They were relatively accessible, fostering a wider awareness, potentially a sympathy, for this segment of the population. Editor: The wheelbarrow itself is quite interesting. It's piled high with hay. He almost seems stooped beneath its weight. There is commentary about back-breaking labor and exploitation to unpack from such simple representation. Curator: Indeed. While some critics accused Millet of socialist sympathies or glorifying poverty, others defended him for his honest representation of rural life. His works certainly sparked conversations about social inequalities, and I'd argue they continue to do so. Editor: It definitely made me pause to reflect on labor in my own time and about issues like the modern-day gig economy and access to proper work conditions. The fact that art can prompt that reflection is powerful. Curator: Absolutely. Millet’s choice of etching further reinforces the working-class subject, an embrace of reproducible media for potentially wide distribution, not necessarily designed for the salons. Editor: So, from a seemingly straightforward image of a peasant, we've delved into a commentary about class, representation, and the politics of visibility. Curator: Exactly. Millet gives us a moment to contemplate those unseen, unacknowledged contributions upon which society rests. Editor: I'll certainly carry that perspective with me. Curator: As will I. Thank you for sharing your insightful reflections.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.