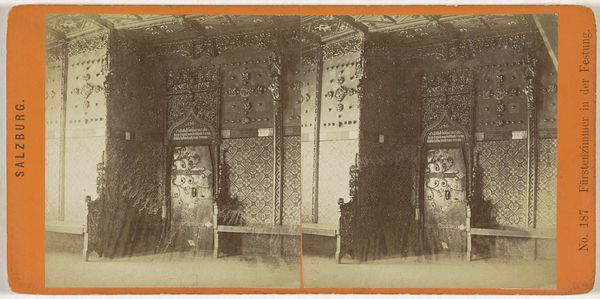

Vorstenkamer ofwel gouden kamer, in de vesting Hohensalzburg 1874 - 1875

0:00

0:00

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

etching

#

personal sketchbook

#

coloured pencil

#

watercolour bleed

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

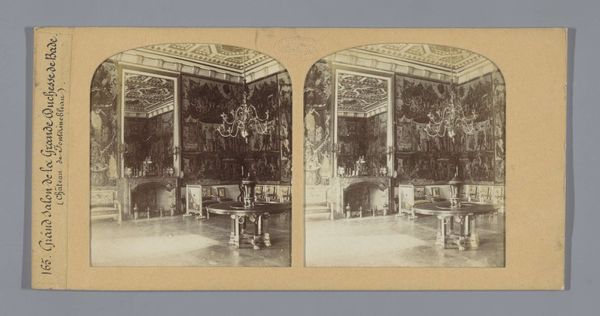

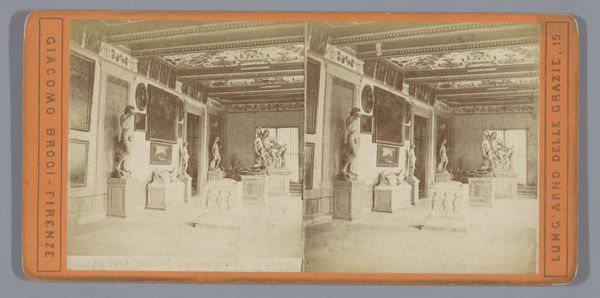

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 176 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This artwork is titled "Vorstenkamer ofwel gouden kamer, in de vesting Hohensalzburg," dating from 1874-1875, by Carl Friedrich Würthle. It depicts an interior, and from a scan of a stereograph, as it were. Editor: It feels so claustrophobic! All those repetitive patterns closing in. I'm immediately struck by this elaborate tile stove—almost like a character standing there. And what I find strange is, who needs such an immense stove in such a rather small room, that itself sits inside a massive castle fortress, high up from the mountains in a very warm region! Curator: Yes, that's a fascinating point. These stereographs were incredibly popular for disseminating images and narratives about power. Showing interiors like the "golden room," and suggesting a particular kind of wealth and aesthetic taste was very on point in the late 19th century. Even now we feel invited into intimate places... as we ourselves consume media on modern day rectangles... a similar effect no? Editor: I suppose...I still think the golden room looks freezing rather than gilded. I just can’t get past this idea that, on a good bright summer, with this room all warmed up with its tile-constructed flamethrower…it can be no place I ever want to visit. Curator: But think of the fortress’ strategic significance. By picturing these private, sheltered spaces, Würthle visualizes ideas of status, comfort and dominion, suggesting this isn't just protection from elements, but a symbolic bulwark. How a powerful stove inside a very small place protects from exterior enemies. It tells viewers, 'Here is wealth and beauty, culture and might!' which are all symbols of 19th century empire and power in themselves. Editor: True, propaganda always works, even subliminally, when showing beauty behind walls and defenses. For me though, that patterned ceiling makes me want to run! It speaks less of sanctuary, and more of stifling decoration, I feel trapped! Perhaps because such patterns no longer resonate... Curator: And maybe that is Würthle's real message: Empires are a good way of living safely, so long as one knows how to look the part in public image. Editor: I guess beauty can really be in the eye of the beholder, or even a well crafted piece of misdirection? Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.