photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

men

#

profile

Copyright: Public Domain

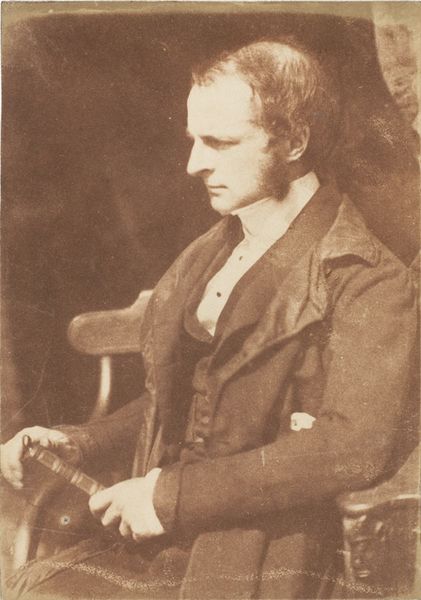

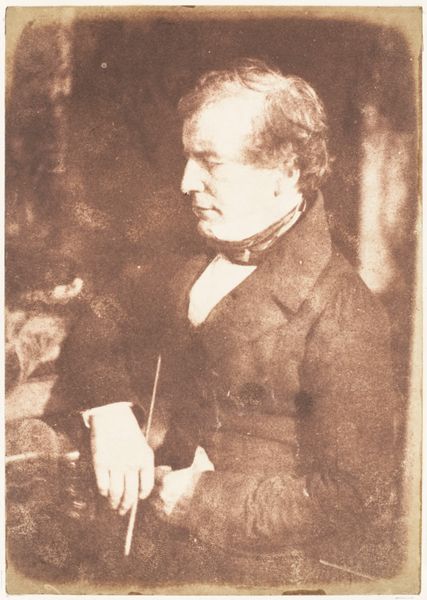

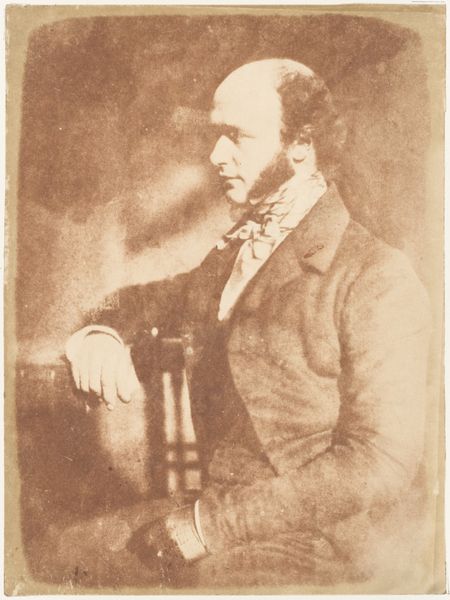

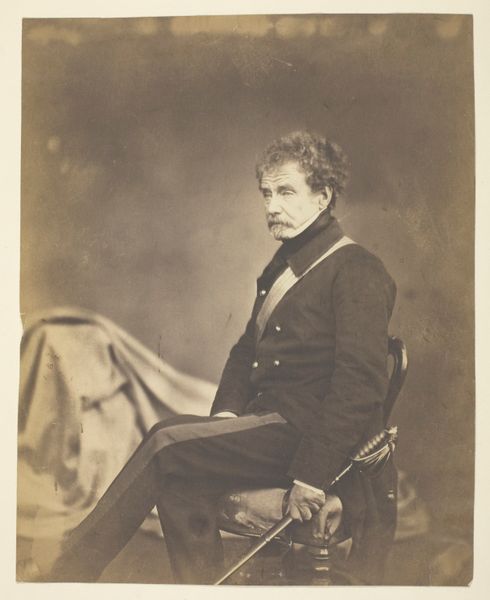

Curator: Looking at "Rev. James Scott," a gelatin silver print made sometime between 1843 and 1847 by Hill and Adamson, currently residing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, it is quite remarkable how well it holds up against time. Editor: There's an undeniable melancholy radiating from the image. The sepia tones lend it a gravitas, and the Reverend's averted gaze suggests a deep introspection or perhaps even weariness. Curator: These early photographs provided a new mode of portraiture that intersected with both Romanticism and burgeoning documentary realism. Here, the Reverend Scott is carefully posed, yet the image maintains a sense of immediacy absent from most paintings. Editor: But what does it mean to have access like this, especially considering what these images communicated back in their time? This photographic technology emerged alongside new levels of colonialism. Were these photographs used to catalog or justify specific racist beliefs? Curator: Precisely, these images played a pivotal role in constructing social narratives. This portrait, specifically, participates in constructing idealized masculinity rooted in Victorian values, where moral authority and intellectual gravitas were paramount. Editor: This feels true for white subjects of these portraits only. The colonial implications complicate any simple understanding of photographic portraiture in this period; so many narratives were crafted at the expense of the colonized. Curator: Absolutely, and examining portraits of this era inevitably raises questions of representation, power, and privilege, and the societal function they performed back then in an overwhelmingly white Western society, as well as their potential to subvert existing societal hierarchies. Editor: So as we appreciate the technical achievement and artistic choices evident in "Rev. James Scott", we must remember to keep looking, digging deeper into who is omitted, or perhaps depicted without their own informed consent, from this historical record.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.