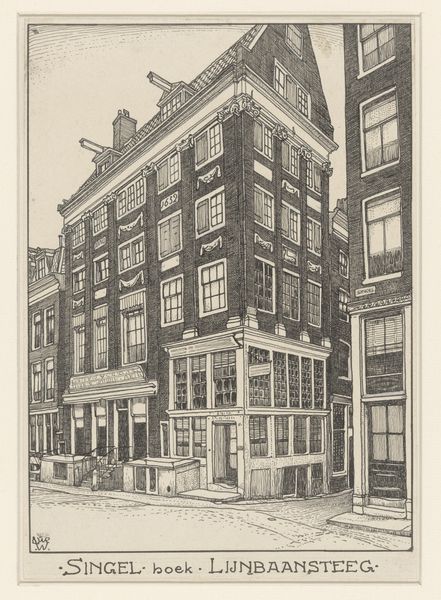

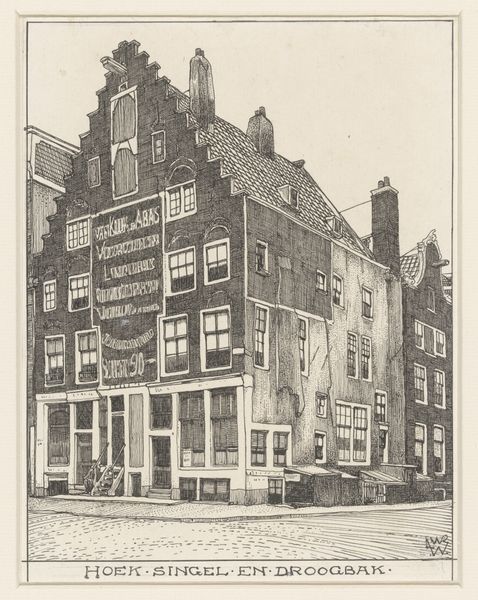

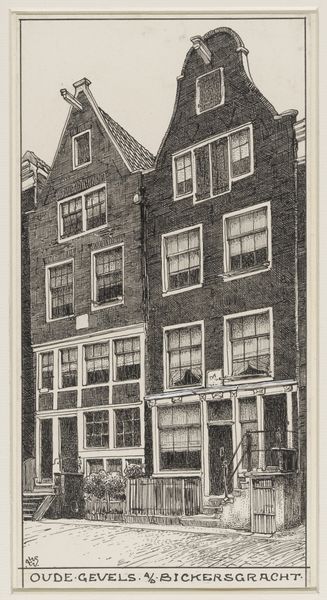

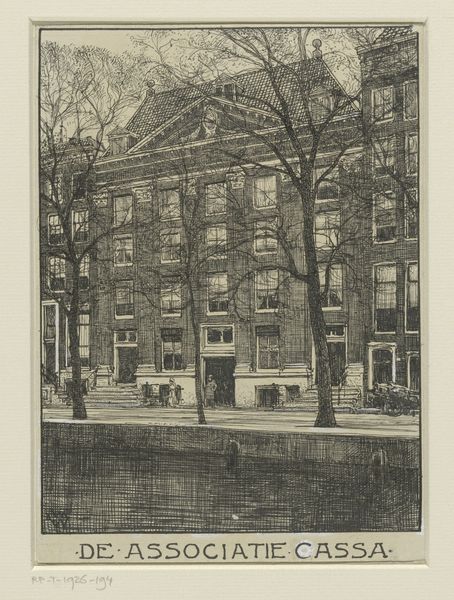

Hoekhuis aan het Rusland en Oudezijds Achterburgwal te Amsterdam 1870 - 1926

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

paper

#

ink

#

line

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 221 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, the drawing feels almost… haunted, doesn’t it? There’s a somberness to it. Editor: Yes, an intriguing choice, this work by Willem Wenckebach. Titled "Hoekhuis aan het Rusland en Oudezijds Achterburgwal te Amsterdam," the Rijksmuseum tells us it was made sometime between 1870 and 1926. Look at the intricate linework done in ink on paper! Curator: That somber feeling, I think, stems from the detail of the drawing. It captures an intimacy of the streets. The lines, while precise, seem to create a labyrinth, hinting at something concealed or perhaps melancholic behind the gables. It evokes a certain unease, a feeling of being watched. Editor: Indeed. Amsterdam's relationship to realism has been complicated, and this aligns with art's complicated relationship with public versus private imagery. One thing Wenckebach certainly understands is the relationship between the buildings and the canal, and, importantly, the viewer's relation to them. See the small indications of labor and commerce like the man near what appears to be some kind of well. The work suggests the daily reality playing out near the grand building. Curator: That makes sense. And it also highlights the symbolic weight of water in art history—water as a mirror, a boundary, a connection to the unconscious. The artist really plays on this tension, between the visible world of commerce and architecture, and the hidden emotional undercurrents flowing beneath. The symbolism here, of societal facades against this more organic emotional force... fascinating. Editor: Right! But Wenckebach wasn’t making art in a vacuum. You see Dutch art of this period engaging actively with rapid industrial and societal changes. They are dealing with the social role of buildings like this. Look at how the shadows play such a central role, and in this way we can see art's public function at this time to represent not just buildings but the politics surrounding these edifices. Curator: Thank you for bringing that aspect in; I have to concede, there’s such density to it! A drawing that contains and creates space for so much—both literally, in terms of the architectural depth, and metaphorically. Editor: Exactly! By placing it in its moment, it resonates differently than a timeless study, or a universal commentary, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.