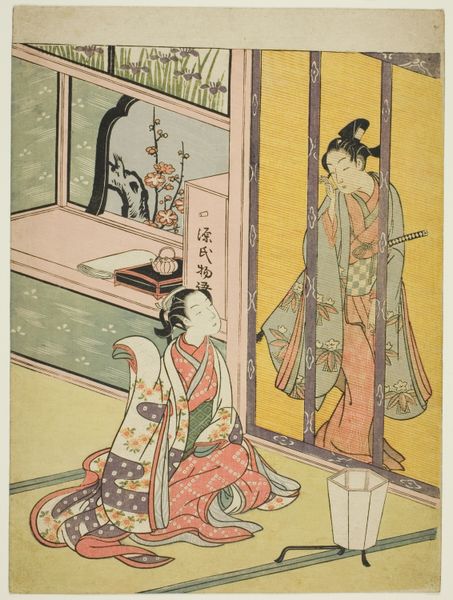

Morning of Iris, from the series "Five Festivals in the Pleasure Quarters (Hanakuruwa gosechi no asobi)" c. 1779

0:00

0:00

print, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 32.3 × 22.9 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This woodblock print, "Morning of Iris," by Torii Kiyonaga, transports us to the Yoshiwara pleasure district of Edo-period Japan, around 1779. Editor: My first impression is of serene activity, an almost dreamlike stillness despite the implied hustle of a festival day. Curator: Kiyonaga, as a leading Ukiyo-e artist, masterfully depicts the leisured class through the lens of idealized beauty, focusing on women's roles within societal events and daily life. In this series, we see "Five Festivals in the Pleasure Quarters". Editor: Note the stylized iris, recurring. Irises symbolize protection from evil. I imagine these women carefully arranging them for a ritual purification of the space. The details are amazing, observe that elaborate knot in the backdrop; its visual impact carries immense cultural weight in its structural and decorative form. Curator: Precisely! Iris became important to celebrate the Tango no Sekku in Japan around the end of the Muromachi Period (1336 to 1573). As a public holiday iris decorations would appear outside building to cast spells against the epidemics, it later became to symbolise wishing well for boy's health and development. And how the figures occupy space reveals class and gender roles during that time. Editor: Look closer at that woman crouching. She arranges the flower but avoids our gaze—her downcast eyes and gesture are symbolic; suggesting deference. Yet, the overall composition is balanced, isn't it? Those layered horizontal lines lead the eye to the taller, standing figure. Her elaborate clothing also suggests her place in the scene, in that society. Curator: Kiyonaga presents a carefully staged scene, not a candid slice of life, emphasizing harmony, decorum, and class distinctions inherent in Japanese society then. By immortalizing these fleeting festivals, Ukiyo-e prints became important sociohistorical records. Editor: Absolutely, through subtle iconography, the work preserves specific cultural narratives. This reminds me of the power of symbolic arrangements to negotiate between ritual space and physical embodiment. Curator: And for me, understanding these nuances reveals complex relationships, how these prints performed their social function then and persist today. Editor: It leaves me with much to contemplate on Japanese cultural norms and aesthetics. Curator: Yes, this one provides us a lens into a very specific historical narrative and is quite beautiful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.