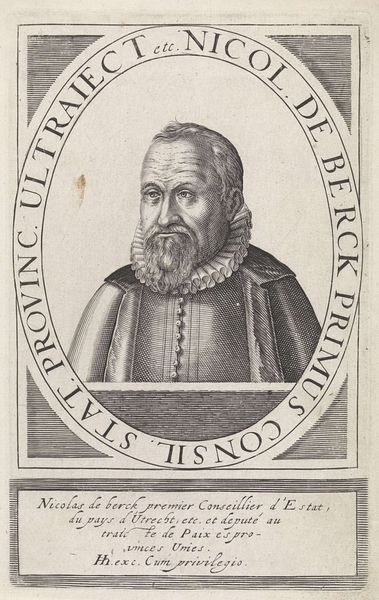

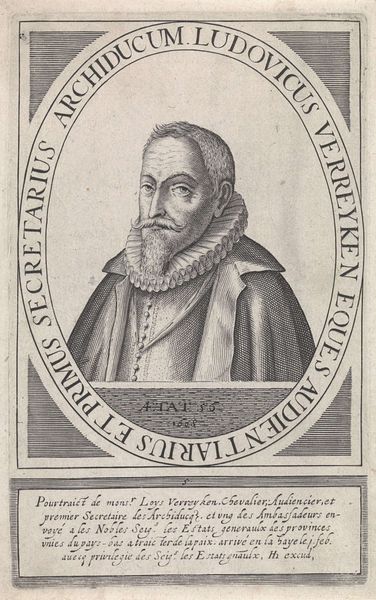

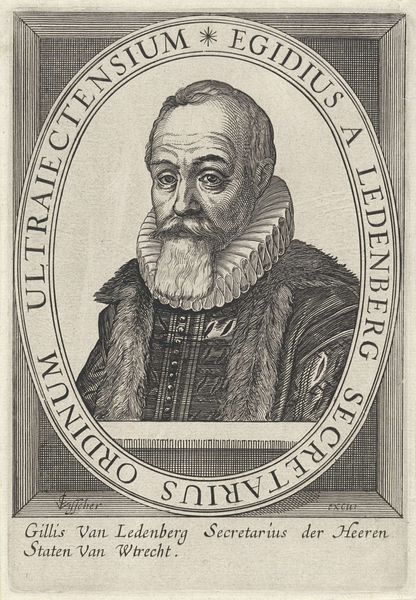

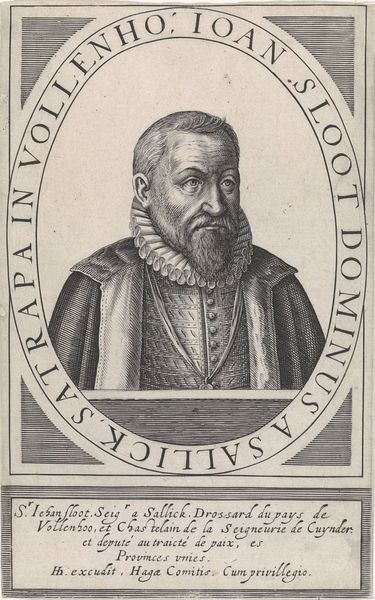

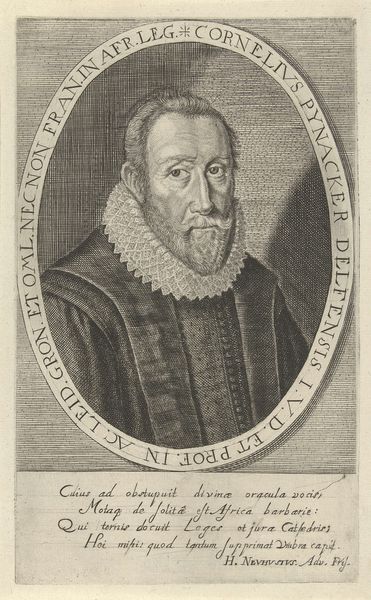

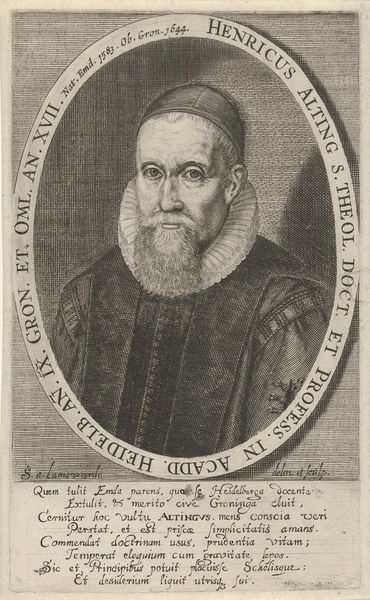

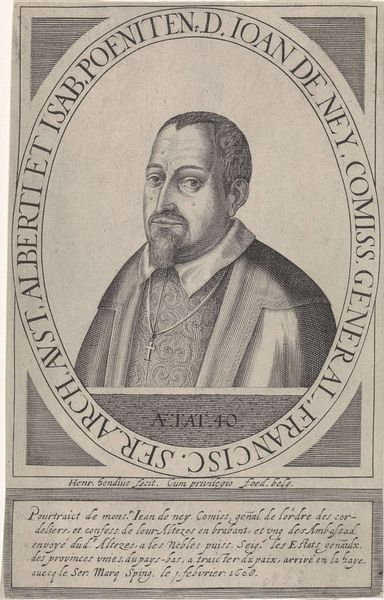

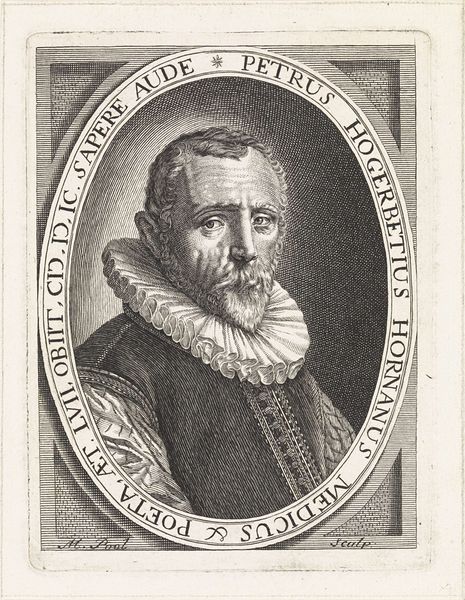

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

#

columned text

Dimensions: height 190 mm, width 122 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Hendrick Hondius I’s “Portret van Jean Richardot,” an engraving from around 1608 or 1609. It's fascinating how detailed they could get with just lines. What strikes me most is how the portrait is framed by all this text. How do you interpret that interplay between image and words? Curator: It’s an excellent observation. The inscription, acting as a frame, literally and figuratively situates Richardot within a matrix of power. The text isn't just descriptive; it actively constructs his identity through titles and associations: "Conseiller de Stat Chief," "President du Conseil Prive." What power structures and social dynamics do you think are at play in choosing to represent someone this way, emphasizing their roles within political and religious institutions? Editor: Well, it feels like it's not just about representing the individual, but also reinforcing the authority of the institutions he represents, almost like propaganda, solidifying existing power dynamics. Is that something printmakers were consciously doing? Curator: Precisely. The print served as a means of disseminating not only his image, but also the ideologies he embodied. Consider the historical context: this was a period of intense political and religious conflict. The details in the portrait—the sitter’s stern expression and the lavish robe—what do these visual elements tell us about the sitter’s beliefs in himself, and in his ability to use that role to bring people together or further divide? Editor: I see what you mean. The seriousness conveyed through his gaze, combined with the robes of high office, communicates a commitment to his role. And maybe the intention was to showcase not just his own convictions, but also to strengthen the power behind the figures aligned to that side of the debate? Curator: Exactly! Hondius wasn't just creating a likeness; he was participating in a much larger conversation about power, representation, and the shaping of public opinion. Editor: I hadn't considered the extent to which even portraiture of this era was so actively engaged in ongoing socio-political narratives. Curator: Yes, and questioning these representations allows us to reveal who benefits from these portrayals, whose stories are centered, and how that reflects and shapes the world we live in now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.