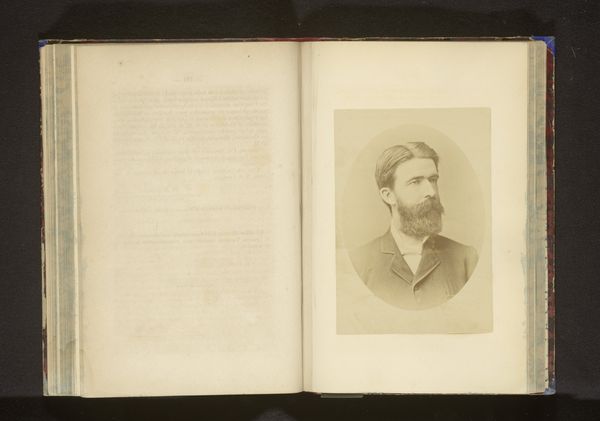

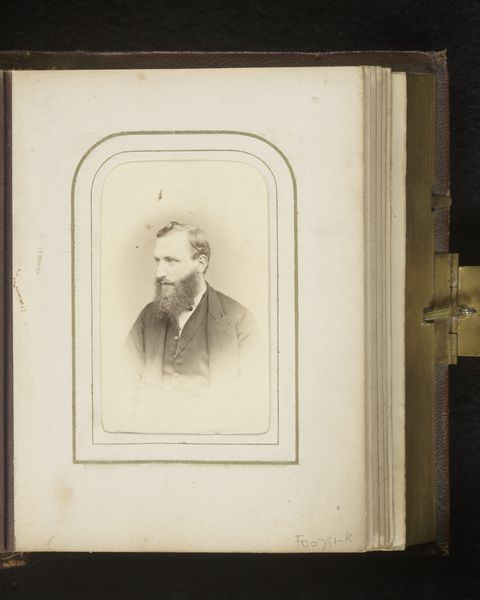

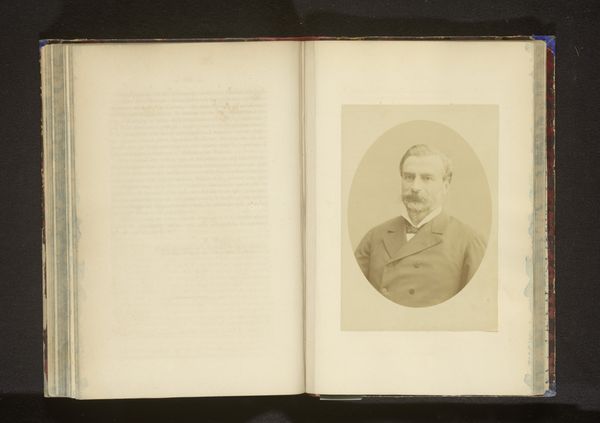

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 146 mm, width 102 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

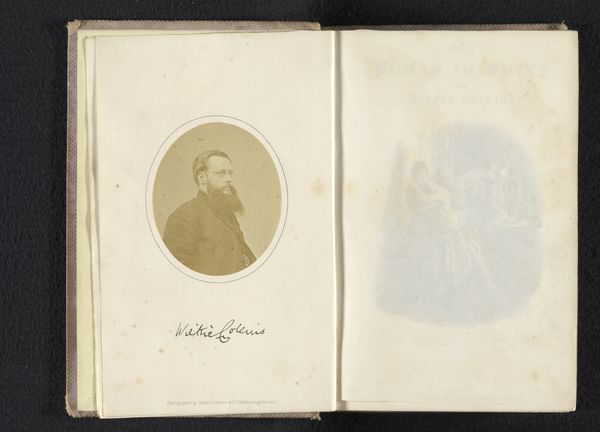

Curator: Here we have a photograph from around 1882 entitled "Portret van Octavio de Bernardieres." It's presented as a gelatin-silver print. Editor: The oval framing immediately makes me think of a locket, or a memento. There’s an intimacy to it despite the formality of the sitter's attire. The monochrome tones evoke a specific mood, melancholy maybe? Curator: Indeed. Photography in the late 19th century, especially portraiture, served specific social functions. The rise of the middle class meant more people could afford to commission images, allowing for the construction and reinforcement of identity and social standing through visual representation. Consider how meticulously Bernardieres presents himself. Editor: Exactly, the carefully trimmed beard, the buttoned jacket. But there's a quiet defiance, or maybe reservation in his eyes. What kind of power dynamics are at play here, between photographer and subject, class and representation, performance and reality? Whose gaze is privileged? I'm curious what narrative lies beneath this polished veneer. Curator: These photographic studios often upheld societal norms. They carefully crafted ideals that affirmed power structures. The framing you mention contributes—ovals and circles evoke classicism and continuity. There are implications regarding aesthetics, aspirations, and cultural legacies imbedded into these conventional photographic decisions. Editor: Perhaps, but even in conforming, he complicates it by offering some resistance through that piercing look. He is self-possessed; not merely a passive participant being rendered to conform. Photography allows more democratization than paintings ever did; but the means, even here, do not guarantee it. Curator: A keen insight. In viewing this piece, then, we should acknowledge the complexity in both representation and the gaze of the subject, and question traditional narratives. The image acts not simply as a memento, but as an artifact loaded with social information. Editor: Ultimately it challenges our own assumptions about how identity is formed, archived, and shared. I come away contemplating the unsaid dialogues, and wondering how my gaze reshapes that history today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.